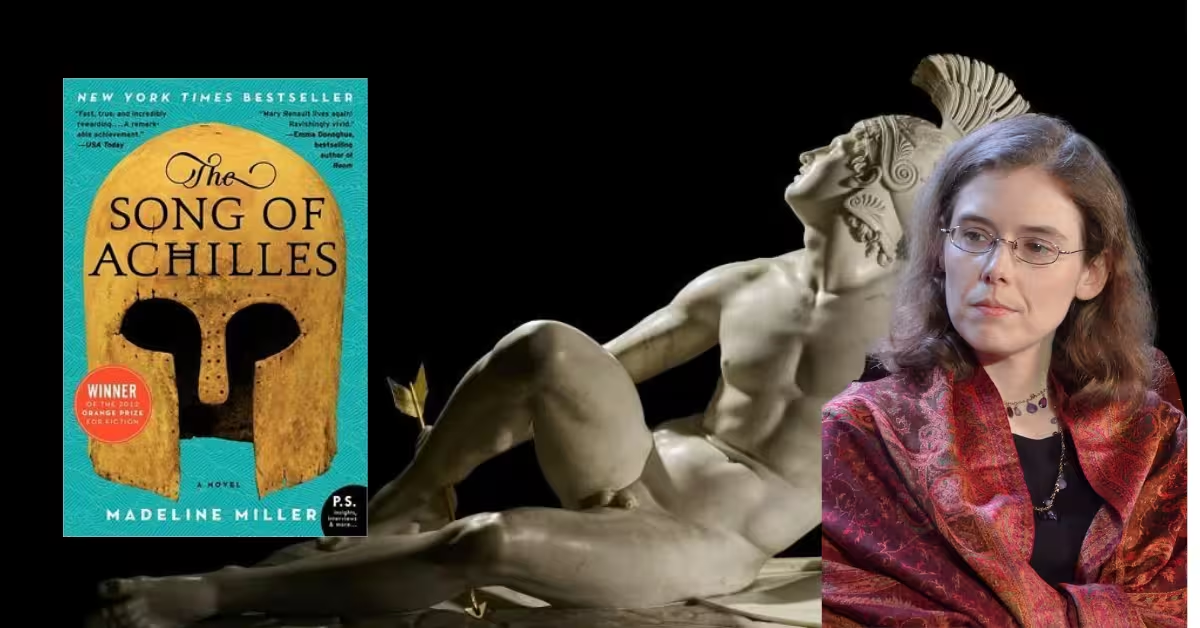

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller is a modern literary reimagining of Homeric legend, first published on September 20, 2011. The debut novel quickly carved a place in literary history, earning the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2012—a rare feat for a first-time novelist.

Blending historical fiction with romance and mythology, The Song of Achilles belongs to the genre of literary romance with strong fantasy elements. The novel retells the tale of the Trojan War not from the viewpoint of the Greek hero Achilles, but from that of his lesser-known companion and lover, Patroclus.

Madeline Miller, a scholar of Greek and Latin, drew deeply from classical sources—particularly Homer’s Iliad, the Achilleid by Statius, and works by Ovid and Aeschylus—to offer a daring, emotional narrative that re-centers myth through the lens of intimate love.

The Song of Achilles is not just a retelling of ancient myth—it is a lyrical exploration of identity, devotion, destiny, and mortality. Miller’s masterful storytelling humanizes gods and heroes alike, transforming a timeless epic into a deeply personal and universal experience. Its enduring popularity—spiking again through BookTok virality with over 2 million copies sold by 2022—testifies to its emotional resonance and literary power.

Table of Contents

Background of The Song of Achilles

Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles is a contemporary retelling of ancient Greek myth, centered on the relationship between the legendary warrior Achilles and his companion Patroclus.

First published in 2011 by Ecco Press, the novel draws heavily from Homer’s Iliad, as well as other classical sources like Ovid, Sophocles, and Statius, reimagining the epic events of the Trojan War through a deeply personal and emotional lens.

The idea for the novel took root in Miller’s childhood, when her mother—a classics teacher—introduced her to the stories of the Greek heroes. Like many readers of the Iliad, Miller was fascinated by the bond between Achilles and Patroclus, which in Homer’s original is ambiguous, intimate, and emotionally intense but never explicitly romantic.

Ancient Greek writers and philosophers—such as Aeschylus and Plato—often interpreted their relationship as a romantic one. Inspired by these interpretations, Miller set out to explore their story from Patroclus’s perspective, giving voice to a character often relegated to the margins of myth.

Miller spent over a decade researching and writing the novel. At one point, after completing a full manuscript, she discarded it entirely and started over to refine the narrative voice and emotional tone. The result was a poetic and lyrical novel told in the first person by Patroclus, capturing his transformation from an exiled, awkward child into the courageous, loyal companion of Greece’s greatest warrior.

Although The Song of Achilles is rooted in classical literature, it breaks away from the traditional heroic mold. Rather than focusing on military glory or political drama, Miller brings forward themes of vulnerability, forbidden love, identity, grief, and the human cost of war. The novel portrays Achilles not only as a demigod or soldier, but as a boy in love, torn between prophecy and passion.

Upon release, The Song of Achilles was met with widespread acclaim. It won the 2012 Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize for Fiction), making Miller the fourth debut novelist to receive the honor. The book became a bestseller in multiple countries and experienced renewed popularity in 2021 thanks to viral attention on TikTok’s “BookTok” community.

The novel’s unique blend of myth and intimacy, historical fidelity and modern emotion, has made it a landmark of queer historical fiction and a gateway into Greek mythology for new generations of readers.

Who Was Achilles?

Achilles, one of the most legendary heroes in Greek mythology, was the son of the mortal king Peleus and the sea goddess Thetis. Known for his unmatched strength, divine lineage, and extraordinary beauty, Achilles was destined to become the greatest warrior of his generation.

From birth, his life was intertwined with fate and prophecy. According to myth, Thetis tried to make him immortal—most famously by dipping him into the River Styx, making his body invulnerable except for the heel by which she held him. This vulnerable spot would later become the root of the term “Achilles’ heel.” Trained by the wise centaur Chiron, Achilles was not only skilled in combat but also well-versed in medicine, music, and philosophy, making him a symbol of both physical and intellectual excellence.

In The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller reimagines Achilles not just as a warrior destined for glory, but as a complex young man deeply in love with his companion, Patroclus. This retelling strips away the armor to reveal the heart of the myth—Achilles’s loyalty, pride, and grief.

Rather than glorifying war, Miller paints Achilles as torn between his thirst for eternal fame and his all-consuming love for Patroclus. Through Patroclus’s eyes, Achilles is not just a demigod or hero, but a boy marked by love, sacrifice, and sorrow.

His legacy, immortalized in Homer’s Iliad, has endured for millennia—but The Song of Achilles redefines that legacy through tenderness, intimacy, and humanity.

The Song of Achilles Summary

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller is a powerful, lyrical retelling of the Iliad through the voice of Patroclus, a minor character in Homer’s original epic, reimagined here with psychological depth, tragic tenderness, and romantic intensity.

The novel is not only an exploration of the Trojan War, but also a coming-of-age and love story between Patroclus and Achilles that centers human emotion amidst legendary events.

The Beginning: Exile and Meeting Achilles

The story opens with Patroclus, a young Greek prince, narrating his lonely and emotionally deprived childhood. He is the awkward, unloved son of King Menoetius, rejected by his father for being unexceptional—small, quiet, and clumsy. His mother is mentally disabled, and Patroclus quickly learns to navigate his father’s world by remaining silent and unnoticed.

His life takes a decisive turn when, at nine years old, he is taken to Sparta as one of Helen’s suitors. When Helen chooses Menelaus, the other suitors—including Patroclus—are made to swear a blood oath to defend the marriage. This promise later binds him to the Trojan War.

Back home, tragedy strikes when Patroclus accidentally kills a nobleman’s son, Clysonymus, during a fight over a pair of dice. Though it’s an accident, the political implications are serious. To avoid scandal and war, his father exiles him to Phthia, a small but noble kingdom ruled by King Peleus.

There, Patroclus meets Peleus’s son Achilles, a golden child said to be the son of the sea goddess Thetis. Achilles is beautiful, fast, and gifted—everything Patroclus is not. The two boys could not be more different, and yet, through a series of quiet moments, they begin to form a bond. Achilles chooses Patroclus as his companion, bringing him out of his emotional isolation.

Growing Together: From Companions to Lovers

As the boys grow older, their friendship deepens. They learn music, poetry, and warcraft under the guidance of the centaur Chiron on Mount Pelion, after Thetis, who despises Patroclus, tries to separate them. Despite Thetis’s disapproval and society’s expectations, their relationship blossoms into romantic and sexual love.

Achilles is confident and proud of his divine heritage. Patroclus, on the other hand, is filled with doubt. Yet in each other’s company, they find solace, safety, and freedom. Their years under Chiron are portrayed with pastoral beauty—learning how to heal wounds, hunt, live in harmony with nature, and make love under the stars.

But peace is fleeting. The outside world begins to change. Helen is kidnapped by Paris of Troy, and war is inevitable. Agamemnon, the Mycenaean king and Helen’s brother-in-law, calls on all the former suitors to honor their oath. Achilles is prophesied to be the greatest warrior of his generation, and central to Greece’s victory. However, the prophecy also states that if he goes to Troy, he will die.

Thetis, desperate to avoid this fate, hides Achilles on the island of Skyros, disguised as a girl. Patroclus follows him there. But the ruse fails when Odysseus, crafty and clever, discovers Achilles’s identity and forces his hand. Achilles joins the war. Patroclus, bound by the blood oath he once took, must follow too.

The Trojan War: Honor, Rage, and Conflict

The Trojan War does not unfold as expected. When the Greek fleet is stuck due to unfavorable winds, Agamemnon is advised to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the goddess Artemis. The brutality of this act introduces a recurring theme: the costs of war and ambition. Achilles is deeply disturbed by the killing, and tension simmers between him and Agamemnon.

Upon arrival at Troy, Achilles quickly earns fame by slaughtering Trojan warriors, including entire families. However, he refuses to kill Hector, Troy’s greatest warrior, because doing so would start the chain of events leading to his death, as prophesied.

Despite this, Achilles becomes a war hero. Meanwhile, Patroclus—unsuited to war—takes on the role of healer and comforter, bonding with other Greeks, particularly Briseis, a Trojan woman taken as a spoil of war. Though she is originally given to Achilles, she becomes closer to Patroclus, forming a deep platonic bond.

Nine years pass. The war drags on. Then a major conflict erupts between Achilles and Agamemnon. When Agamemnon is forced to return Chryseis, his war prize, he compensates by seizing Briseis from Achilles. Achilles, enraged by the insult, withdraws from the war, refusing to fight.

Patroclus tries to mediate, but Achilles is prideful and unyielding. Without Achilles, the Greeks begin to lose ground. As the Trojan army pushes back the Greeks to the brink of defeat, Patroclus becomes desperate to save his comrades.

Patroclus’s Heroic Stand and Death

Patroclus hatches a plan: he will wear Achilles’s armor and lead the Myrmidons into battle, hoping to boost morale and trick the Trojans into retreat. Achilles initially resists but ultimately relents—on the condition that Patroclus returns immediately after pushing the Trojans away from the ships.

Patroclus dons the armor and charges into battle. His courage and compassion transform into reckless bravery. The ruse works—the Trojans retreat. But Patroclus, emboldened and carried away by the moment, defies Achilles’s instructions and continues fighting. He kills Sarpedon, a son of Zeus, and nearly reaches Troy’s gates.

Then, tragedy strikes. Apollo, the god, intervenes, knocking off Patroclus’s armor. Hector seizes the opportunity and kills him. With Patroclus’s death, the novel enters its most painful phase.

Achilles’s Grief and Final Destiny

Achilles’s reaction to Patroclus’s death is devastating. He refuses food, sleep, or reason. He publicly mourns Patroclus, defying norms of masculinity and heroism. He orders Patroclus’s body to be prepared for burial, but delays the cremation, weeping over his corpse for days.

Eventually, Achilles returns to the battlefield, driven not by glory but by vengeance. He kills Hector in a brutal duel, drags his body behind his chariot, and desecrates it daily despite pleas from Hector’s father, King Priam.

Yet Achilles’s fate looms. Shortly after, he is killed by Paris with an arrow guided by Apollo. Before dying, he begs that his ashes be mixed with Patroclus’s.

However, after his death, his son Neoptolemus arrives and prevents Patroclus’s name from being carved onto Achilles’s tomb. As a result, Patroclus’s spirit is trapped, unable to enter the underworld.

The Afterlife and Final Reunion

After Achilles’s death, the novel takes a surprising turn—narration continues from Patroclus’s disembodied spirit. While his ashes were mixed with Achilles’s as promised, the tombstone bears only Achilles’s name. This omission leaves Patroclus’s soul trapped between the worlds of the living and the dead. In Miller’s mythology, names are powerful. Without recognition, the soul cannot pass into the afterlife.

Patroclus remains a ghost at the edge of the world, tethered to the tomb where his body rests. He observes the aftermath of the war, powerless but still deeply tied to the world he left behind. Neoptolemus, Achilles’s cold and arrogant son by Deidamia, comes to Troy and takes up his father’s legacy as a warrior. But unlike Achilles, Neoptolemus lacks compassion and humility. He’s ruthless, a contrast that adds new pain to Patroclus’s lingering spirit.

When Briseis—Patroclus’s dear friend—rejects Neoptolemus’s advances and tries to protect Achilles’s legacy, Neoptolemus kills her. Her death devastates Patroclus, who had promised to protect her. Now powerless and bodiless, he can only witness the destruction Neoptolemus causes in the name of his father.

Eventually, the Greeks leave Troy. The war ends, but Patroclus’s suffering continues. His soul lingers, invisible and voiceless, denied peace or recognition.

Thetis’s Transformation

In time, Thetis—the sea goddess and Achilles’s mother—returns to the site of the tomb. Still proud and cold, she initially shows no concern for Patroclus. For much of the novel, Thetis had been a distant and controlling presence, determined to shape Achilles into a godlike hero and to keep him away from Patroclus. She considered Patroclus beneath her divine son—unworthy and mortal.

But as the years pass, Thetis returns again and again to the tomb. With no one left to grieve with her, she begins speaking to Patroclus’s ghost. Slowly, something begins to shift. The barrier of disdain softens. She begins to ask Patroclus about her son—not just the warrior, but the boy, the friend, the lover. In these rare, gentle moments, Thetis and Patroclus find common ground: they both loved Achilles deeply, though in different ways.

Patroclus shares stories of their childhood, of the quiet intimacy between them, of Achilles’s laughter, his dreams, and fears. Through these conversations, Thetis comes to see that Patroclus was not Achilles’s weakness, but his soul’s other half. She had misunderstood the nature of love, thinking glory and greatness were all that mattered. Now, in the absence of both, she begins to understand the cost.

The Final Act of Mercy

In the novel’s final act, Thetis performs one last, unexpected kindness. Recognizing Patroclus’s suffering and love, she uses her divine influence to inscribe his name on the tomb alongside Achilles’s. This simple act—of giving a name—breaks the curse that has kept Patroclus’s spirit bound.

With the inscription complete, Patroclus is finally free to pass into the afterlife. The narrative’s voice lifts as he rejoins Achilles’s soul in eternity. The final paragraphs of the novel are deeply emotional and tender: the two lovers, at long last, are together again—beyond war, beyond pain, beyond the reach of time.

“In the darkness, two shadows, reaching through the hopeless, heavy dusk. Their hands meet, and light spills in a flood like a hundred golden urns pouring out of the sun.”

This ending transforms what had been a story of inevitable tragedy into one of timeless, transcendent love. It is not Achilles’s war feats or Patroclus’s death that remain with the reader—it is their bond, fragile yet eternal, that defines the novel.

Themes and Character Arcs

1. Love and Identity: At the heart of The Song of Achilles is a love story—unapologetically queer, vulnerable, and powerful. Miller reclaims the ancient bond between Achilles and Patroclus, giving it emotional and sexual depth often ignored in traditional retellings. Their love is shown as formative, not secondary. It shapes their decisions, their loyalty, and their legacy.

Patroclus grows from an insecure, exiled boy into a man of strength and empathy—not by learning to fight, but by staying true to his values. Achilles, initially proud and golden, slowly becomes more complex. His struggle between fame and love, prophecy and choice, is central to the emotional weight of the story.

2. Fate vs. Free Will: Greek myth always dances on the line between destiny and choice. Achilles is fated to die young if he chooses glory. Yet even knowing this, he willingly goes to Troy, thinking he can still control how the story unfolds. In contrast, Patroclus has no prophecy guiding him—but his choices are radical in their quietness. His love, his defiance, his refusal to worship glory all become forms of rebellion against a world obsessed with heroism.

3. War and its Costs: While Homer’s Iliad celebrates epic battles and honor, Miller’s retelling is unflinching in its depiction of war’s cost. Through Patroclus’s eyes, we see the brutality, waste, and moral ambiguity of battle. He serves as a medic, caring for wounded soldiers, forging bonds with the enemy’s victims like Briseis. The emotional and human cost of war becomes more important than its spoils or songs.

4. Immortality and Memory: A recurring motif in the book is the fear of being forgotten. Achilles seeks immortality through fame. Patroclus seeks immortality through love. In the end, both achieve it—but not in the way Achilles expected. It is not his heroic deeds that preserve him, but the fact that someone loved him enough to remember the boy behind the legend. Memory, Miller argues, is a different kind of immortality.

The Song of Achilles is both deeply faithful to myth and radically new. Through Patroclus’s voice, we don’t just see a legendary tale—we live it. We feel the ache of exile, the joy of companionship, the terror of battle, and the sharp grief of loss. By the end, the novel doesn’t simply retell the Iliad—it rewrites it.

Madeline Miller’s greatest achievement is perhaps this: she transforms a war epic into an intimate tragedy, and then—through mercy and memory—into a love song. A song that lingers long after the final page is turned.

“We were like gods at the dawning of the world, and our joy was so bright we could see nothing else but the other.”

Analysis

a. Characters

In The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller crafts characters who are not just mythic figures but fully realized individuals driven by fear, desire, and love. The central focus is on the bond between Patroclus and Achilles—a relationship that reshapes the very tone of the ancient myth.

Patroclus

Often a footnote in Greek mythology, Patroclus is the emotional core of the novel. From a shamed exile to a beloved companion, his transformation is quiet yet profound. He narrates with aching vulnerability, allowing readers into the soft underbelly of myth. His voice—gentle, observant, self-doubting—forms the moral compass of the novel. “He is worth ten of you. The best of all the Greeks,” he declares of Achilles (Miller, Ch. 19). It’s in this devotion that we see the depth of his character—not just a lover, but a man of principle.

Achilles

Achilles, the “best of the Greeks,” is a demigod whose destiny both elevates and isolates him. He is beautiful, yes, but not flawless. Miller shows his pride, his stubbornness, his blind spots. Yet she also gives him humanizing touches: his laughter, his awkwardness, and most heartbreakingly, his grief. “I wish he had let you all die,” he says when Patroclus dies, “so that he could be alive” (Miller, Ch. 29).

Achilles’s conflict between personal love and heroic destiny fuels the tragedy. His refusal to fight is not cowardice but a cry against a future he cannot escape.

Thetis

As Achilles’s mother and a sea goddess, Thetis represents divine power and the coldness of fate. She is not villainous, but deeply wounded. Her resistance to Patroclus reflects her desire to protect her son. Yet in the end, it is her—not Achilles—who brings peace to Patroclus’s soul. “Go to him,” she says in the final chapter, her bitterness softened by grief (Miller, Ch. 32).

Odysseus, Briseis, Agamemnon, Hector, and Others

Miller breathes life into supporting characters. Odysseus is wry and cunning, Briseis is warm and tragically underused by fate, while Agamemnon’s pride leads to chaos. Even Hector, often idealized, is shown as a mirror to Achilles—brave, doomed, and beloved.

In total, Miller’s characters in The Song of Achilles aren’t just players in a myth—they are people you weep for.

b. Writing Style and Structure

Madeline Miller’s prose is lyrical without being overwrought. Her sentences are tight, poetic, and emotionally loaded. She uses first-person narration to great effect—Patroclus’s voice is intimate, vulnerable, and profoundly human. The pacing varies: the early chapters are quiet, like a coming-of-age novel, while the war chapters pulse with dread and inevitability.

She also utilizes:

- Foreshadowing: “He will not forgive you,” Chiron says about Thetis (Miller, Ch. 13).

- Metaphors: “His eyes were as green as spring leaves” (Miller, Ch. 3).

- Silence and restraint: Often what is not said is more powerful—especially in moments of grief and tenderness.

The structure is linear but punctuated by mythic interludes—prophecies, visions, and dreams. The balance between ancient tone and modern accessibility is masterful. As a result, The Song of Achilles reads like a Homeric epic rewritten in the voice of your closest friend.

c. Themes and Symbolism

Love as Defiance

Above all, The Song of Achilles is a love story. But it’s also a rebellion—against tradition, prophecy, even gods. Their love is not accepted by society or divine will, but it endures. “I would know him in death,” Patroclus says. “At the end of the world” (Miller, Ch. 32).

Fate vs. Free Will

Achilles is fated to die. Patroclus tries everything to avoid this end—persuasion, pleas, even impersonation. But fate wins. The tragedy is not in the dying—it’s in how they try to live before it.

Glory vs. Humanity

Achilles wrestles with kleos (glory) and philia (love). Miller unpacks the cost of heroic ideals. Achilles’s legacy is eternal, but his joy dies with Patroclus. “Phthia is dust now,” Patroclus observes. “Only memory remains.”

Symbolism

- The Fig: A symbol of shared sweetness and fragility. Achilles tosses it to Patroclus as a gesture of welcome (Miller, Ch. 4).

- The Tomb: Their joint burial represents defiance of death itself.

- The Sea: Thetis’s domain and a metaphor for fate—deep, unknowable, and unstoppable.

d. Genre-Specific Elements

As a work of mythological romance, The Song of Achilles leans into character depth and emotional stakes rather than pure plot. Yet Miller honors genre expectations:

- World-building: From the oil-slicked training yards of Phthia to the smoke and blood of Troy, the setting is immersive.

- Dialogue: Modern enough to feel accessible, but still weighted with ancient dignity.

- Pacing: Though it starts slow, the emotional build-up makes the final chapters unforgettable.

Who Should Read This Book?

- Lovers of Greek mythology looking for an emotional, fresh perspective.

- Readers of LGBTQ+ romance who want authenticity without clichés.

- Fans of character-driven literary fiction.

- Students exploring reinterpretations of classical texts.

Excellent! Now let’s move on to:

Evaluation

Strengths

1. Emotional Depth

The greatest strength of The Song of Achilles lies in its emotional realism. Miller allows us into the mind of Patroclus with such sincerity that his pain becomes our pain, his love our longing. When Patroclus watches Achilles from across the room, the prose trembles with restrained desire:

“Those seconds, half seconds, that the line of our gaze connected, were the only moment in my day that I felt anything at all” (Miller, Ch. 4).

2. Reimagining Myth with Fresh Humanity

Madeline Miller humanizes mythic figures with remarkable success. Achilles is not just the Greek war hero—he’s a boy in love, a son torn between duty and feeling, a man who grieves beyond reason. Likewise, Patroclus is transformed from a footnote in Homer to the narrator of a deeply moving epic.

3. Accessible Language

Despite drawing from Homer, Ovid, and Virgil, Miller’s language is clean and graceful. Readers unfamiliar with mythology can still immerse themselves in the story, yet those who know the myths will admire the subtle nods and reinterpretations.

4. Representation and Queer Narrative

Unlike many modern rewritings that skirt around the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles, The Song of Achilles embraces it fully and respectfully. As Miller noted in an interview:

“Many Greco-Roman authors read their relationship as a romantic one—it was a common and accepted interpretation in the ancient world”.

Weaknesses

1. Pacing Issues in the First Half

The first 100 pages of The Song of Achilles focus on the growing relationship between Achilles and Patroclus. While beautifully written, some readers may find the pacing slow. For those expecting war drama from page one, the buildup may feel delayed.

2. Underutilized Supporting Characters

Characters like Briseis and Thetis are emotionally complex, yet their arcs sometimes feel rushed or unresolved. Briseis in particular forms a deep friendship with Patroclus, even showing signs of romantic affection, but this subplot fades quickly.

3. Predictability (Due to Myth)

Because the story is based on the Iliad, readers familiar with the myth may find few surprises in plot. However, Miller’s execution adds such emotional layers that predictability becomes irrelevant.

Impact: Emotional and Intellectual

Reading The Song of Achilles is an act of immersion. It’s hard not to cry. Hard not to mourn. Hard not to ache for two boys who wanted only to live and love freely in a world that would not let them. The novel resonates especially with readers who’ve felt unseen, unheard, or unworthy. Patroclus’s quiet journey is not one of external triumph but internal growth—and that’s what makes it profound.

This book has helped young queer readers see themselves reflected in classical literature. It has also revived interest in ancient myths, encouraging readers to revisit Homer with fresh eyes. In classrooms and book clubs, the discussions it sparks around masculinity, fate, and grief are rich and lasting.

Comparison with Similar Works

Circe by Madeline Miller: While Circe is broader in scope and more solitary in tone, both books share Miller’s signature voice—lyrical, introspective, and myth-informed. Circe offers a female-centered narrative, while The Song of Achilles centers male vulnerability.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker: A darker, more brutal retelling from Briseis’s perspective, it contrasts sharply with Miller’s intimate, romantic lens.

Iliad Translations (e.g., by Robert Fagles or Caroline Alexander): While epic and grand, these translations lack the psychological closeness that Miller provides.

Reception and Criticism

The book received widespread critical acclaim:

- Natalie Haynes praised it as “more poetic than almost any translation of Homer”.

- Mary Doria Russell called its prose “as clean and spare as the driving poetry of Homer” in The Washington Post.

- It won the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2012, beating out high-profile favorites. One judge remarked, “Homer would be proud of her”.

It was also shortlisted for the Stonewall Book Award, and in 2021, TikTok users (#BookTok) reignited its popularity, pushing it to over 2 million copies sold by 2022.

Adaptation

As of 2025, there is no official film or TV adaptation of The Song of Achilles, though there have been strong fan calls and rumors circulating. Given the success of adaptations like Troy (2004) and the rise of myth-based series (Percy Jackson, The Witcher), an adaptation seems inevitable.

Until then, many fans imagine Call Me by Your Name meets Troy—a blend of tender love and brutal destiny.

Additional Notable Facts

- Miller spent 10 years writing the novel, rewriting it from scratch halfway through because she couldn’t find Patroclus’s voice.

- The book continues to be one of the most recommended titles on TikTok’s BookTok, particularly among younger LGBTQ+ readers.

Personal Insight

Reading The Song of Achilles is not merely a literary experience—it’s a human one. As someone who has personally turned each page with a mix of reverence and heartbreak, I can say this novel reached into places untouched by most ancient or modern texts. It didn’t just retell mythology—it resurrected it with a beating heart.

At its core, this novel is about a boy who thinks he is not enough—too quiet, too slow, too small to matter. Patroclus is the shadow of every student who has ever sat at the back of the classroom, every young person unsure if they deserve to take up space. But Miller changes that narrative. She gives Patroclus a voice—and through it, she gives voice to anyone who’s ever been silenced.

“I could recognize him by touch alone, by smell; I would know him blind, by the way his breaths came and his feet struck the earth. I would know him in death…” (Miller, Ch. 29).

From an educational perspective, The Song of Achilles offers incredible interdisciplinary value:

Literature and Classical Studies

Students studying Homer, Greek epics, or mythology can use this novel as a companion text. It provides a postmodern lens through which to understand ancient values of heroism, fate, and honor—while challenging those very ideals. In contrast to Homer’s glorification of kleos (glory), Miller paints glory as tragic, fragile, and empty without love.

Gender and Queer Studies

This book is a gentle but firm protest against erasure. It reclaims a queer narrative that history often tried to bury beneath euphemism. In classrooms where discussions about gender, queerness, and masculinity are growing, The Song of Achilles is not just relevant—it’s essential. It proves that ancient stories belong to everyone.

Philosophy and Ethics

Fate vs. free will, the cost of greatness, the moral weight of war—these are questions philosophers have debated for millennia. Miller presents them through lived experience. Achilles chooses his fate, and in doing so, must let go of love. Patroclus fights fate, and in doing so, gains immortality in a different way—through memory, tenderness, sacrifice.

In a world increasingly obsessed with performance, recognition, and legacy, The Song of Achilles asks: what if love is the greatest legacy of all?

The Song of Achilles Quotes

- “He is half of my soul, as the poets say.”

→ A heartbreaking reflection by Patroclus that captures the depth of his bond with Achilles. - “I could recognize him by touch alone, by smell; I would know him blind, by the way his breaths came and his feet struck the earth. I would know him in death, at the end of the world.”

→ A haunting expression of devotion, emphasizing love beyond the physical and even beyond life. - “We were like gods, at the dawning of the world, and our joy was so bright we could see nothing else but the other.”

→ This line paints their love as divine, timeless, and blinding in its intensity. - “Name one hero who was happy.”

→ Achilles’ philosophical musing on fate and glory that runs throughout the novel. - “There is no law that gods must be fair, and perhaps it is that which is most frightening.”

→ A stark reminder of the cruelty and indifference of the divine in Greek myth. - “I will never leave him. It will be this, always, for as long as he will let me.”

→ A quiet vow of loyalty from Patroclus, revealing the unwavering commitment in their relationship. - “When he died, all things soft and beautiful and bright would be buried with him.”

→ A poetic expression of how Achilles’ death would extinguish all meaning and beauty in Patroclus’s life. - “You will not speak another word or you will cry for it. I will cut your lying tongue from your mouth.”

→ Achilles’ wrath in defense of Patroclus shows the fierce protectiveness at the heart of their love. - “We were boys who had nothing, and thus we risked everything.”

→ A powerful encapsulation of youthful love and the danger of loving too deeply in a world shaped by war. - “And perhaps it is the greater grief, after all, to be left on earth when another is gone.”

→ A reflective line on loss and the pain of survival after the death of a loved one.

Conclusion

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller is not just a novel—it’s an elegy for the forgotten, a love song for the silenced, and a resurrection of human feeling in the bones of myth. It is both fierce and fragile, much like Patroclus himself, offering readers a story that aches with devotion and defies the weight of destiny.

Miller reimagines the ancient tale not as a celebration of conquest, but as a quiet resistance against cruelty, conformity, and erasure. Through Patroclus’s eyes, we see that love is not a distraction from greatness—it is greatness. And Achilles, for all his prowess, is never more heroic than in the moments he allows himself to be tender.

“He is half of my soul, as the poets say” (Miller, Ch. 11).

“And perhaps it is the greater grief, after all, to be left on earth when another is gone” (Miller, Ch. 30).

These lines stay with you long after the last page, like a soft bruise on the heart.

Recommendation

Who should read The Song of Achilles?

- Anyone who has loved deeply and lost.

- Students of literature, mythology, gender studies, or philosophy.

- Fans of character-driven, emotionally rich novels.

- Readers looking for LGBTQ+ representation that is organic, powerful, and mythically rooted.

This is a book for those who’ve ever felt like their voice didn’t matter. It whispers to them that it does—that memory can be a form of resurrection, and love, a kind of immortality.

Why This Book Matters Today

In a world where myth and media often glorify war and glory, The Song of Achilles reminds us of the cost of those ideals. It shows that there is beauty in gentleness, courage in vulnerability, and strength in simply being kind. As education shifts toward empathy and inclusion, this novel deserves a permanent place in modern reading lists—not just as literature, but as life lesson.

The Song of Achilles is not only a retelling. It is a reclaiming.