The Uncool summary: chapters, themes, quotes, analysis

Memoirs about fame usually polish the mirror; The Uncool: A Memoir shows you the fingerprints. Crowe solves a timeless problem for music lovers and movie fans alike—how to reconcile the myth of rock ’n’ roll with the messy, human truth that actually happened.

This is Cameron Crowe’s field report from the front lines of 1970s music and family life—a teenager’s apprenticeship in curiosity that became a life in storytelling.

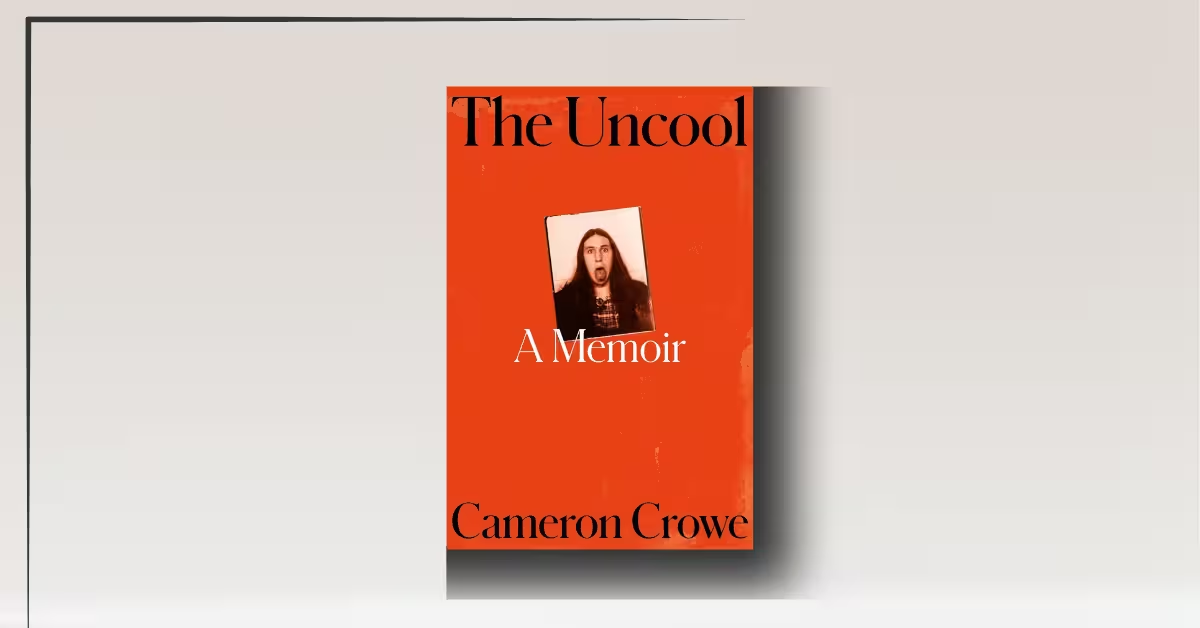

Publication was announced for 28 October 2025 in both the U.S. (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster) and U.K./Commonwealth (4th Estate/HarperCollins) with hardback, ebook, and audiobook editions, confirming the book’s scope and positioning.

Early reception cites Crowe’s teenage reporting, his interviews with Bowie, Led Zeppelin, and others, and the memoir’s structure of short, vivid chapters framed by his mother Alice’s aphorisms.

Inside the text, Crowe anchors scenes with specific, verifiable detail—like an Elvis Presley concert that ran exactly “forty-seven minutes”—a hallmark of a reporter’s notebook now fueling a memoirist’s candor.

The opening pages place the story in 2020s San Diego rehearsals for Almost Famous: The Musical, punctuated by his mother’s mantra—“The only true satisfaction comes from doing good”—which signals the memoir’s ethical spine.

Best for: readers of music journalism, rock history, film culture, and anyone who loved Almost Famous and wants the true stories behind the scenes; also for creative people seeking a humane, non-cynical guide to artistic persistence.

Not for: readers wanting a salacious tell-all, a strict chronological cradle-to-now timeline, or a step-by-step screenwriting manual—this is a mosaic of moments, not a mechanical how-to.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The Uncool: A Memoir by Cameron Crowe was first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate and in the United States by Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster) in 2025.

Crowe’s background is unique: a teenage music journalist in the early 1970s who later became the Oscar-winning writer-director of Almost Famous, Jerry Maguire, and Say Anything…. Major outlets previewed the book as his long-awaited return to his first calling—reporting with heart.

Purpose and thesis. The book argues quietly but consistently that curiosity, decency, and attention—not access, not coolness—are the superpowers of a life in the arts. You see it from page one: a son calling his ninety-seven-year-old mother from outside the Old Globe Theatre, caught between fear of failure and the pull of the work, as Alice Crowe orders him to change his mindset: “Mind is in every cell of the body! What you say will make it so.”

2. Background

Crowe frames his youth in Southern California—Indio, San Diego, Hollywood—not as a backstage pass so much as a series of thresholds he keeps crossing with a notebook and a tape recorder.

In one early thread he recounts the radio-contest hack that won him event tickets, the opening move in a teenager’s hustle toward proximity with the music he loved.

Those tickets became story fuel. He and his mother attend an Elvis Presley show in San Diego: hucksterism, scarves, and a martial-arts-pose spectacle punctured by a single, soul-honest “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” Then, a week later, Derek and the Dominos blaze through a “real rock concert.” The side-by-side scenes teach a reporter’s lesson: tone and truth can change song to song, night to night.

As outside sources remind us, Crowe wasn’t just any teen in the seats: by age 15 he was on assignment, beginning the career that this book re-maps with wisdom gathered over five decades.

3. The Uncool Summary

The essentials at a glance

- Opening frame & core ethic. The memoir opens with Cameron Crowe calling his 97-year-old mother, Alice, from outside the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego during the final stretch before the first previews of Almost Famous: The Musical. It begins under her epigraph, “The only true satisfaction comes from doing good,” and her no-nonsense nightly check-in: “How’s the play?”

- Teen reporter origin story—two concerts, two truths. As a contest-winning high-schooler, Crowe lands four Elvis tickets and trades two for Derek and the Dominos; he ends up taking his mom to both shows. Elvis’s San Diego set is a spectacle of karate poses and backstage limos, punctuated by a startlingly sincere “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” and it lasts exactly “forty-seven minutes.” A week later, Layla and Other Love Songs is “only two weeks old” when Clapton’s band burns at arena peak: “Now, this was a real rock concert.”

- Mother, classroom, and a writer’s naming. In San Diego, Alice reinvents herself as a beloved community-college teacher and counselor; she covers the walls with aphorisms (quoting Teilhard de Chardin) and even invites César Chávez to speak. After the talk, Chávez greets teenage Cameron—“I hear you’re a writer”—which lands as the first time he’s publicly named that way.

- Bowie, Los Angeles, and the reporter’s mirror. David Bowie tells the nineteen-ish Crowe: “You can ask me whatever you want. Hold up a mirror and show me what you see,” then lets him tag along through 1975–76 projects, paranoia, and persona-building (“LA is my favorite museum”). In the studio, Bowie writes by cutting and rearranging lyric strips—“‘Audience’ is the title … the fragmentation is more eloquent than trying to stay linear.”

- Petty, 1982—camera as pen. On a November 1982 Winnebago ride to shoot “You Got Lucky,” Tom Petty strums Elvis tunes and recalls meeting Presley as a ten-year-old in Gainesville during the filming of Follow That Dream; Crowe feels a creative “elixir” as Petty orders, “Pick up the camera and shoot,” tipping him from journalism toward filmmaking.

- Family ache & the private soundtrack. The childhood fairy-tale “ting” motif folds into the memory of Cathy, Crowe’s eldest sister (“In May of 1957, Cathy was only ten years away from the dark July when she left us”), and the shared music (Brian Wilson, the Tremeloes, Joni Mitchell) that became their emotional beacon—“My music was her music. It was our ting.”

Detailed Summary

A son, a notebook, and a late-night phone call. The book begins in a moonlit courtyard at the Old Globe, less than ten days before the first preview of Almost Famous: The Musical. Crowe confesses to us—and to his mother Alice—that the show “was not going to work,” a truth he dreads voicing to her; the preface’s epigraph, “The only true satisfaction comes from doing good,” makes clear this will be a memoir braided with conscience. The staging smells of gardenias, but the dramatic engine is maternal candor and a grown child’s fear of disappointing her.

Before the red light—winning tickets, riding buses, and learning to watch. Crowe’s apprenticeship isn’t glamorous; it’s logistical. He becomes a contest-winning savant and hustles his way to live shows. His comic dread about being “unhip” on a mom-and-son Elvis date dissolves as he realizes they might actually be the coolest people in the building—two clear-eyed observers in a sea of “jolly blue-haired ladies.”

The pre-show is sales patter and hype—scarves hawked and Pat Buttram tracking Elvis’s plane “as if describing Santa Claus”—teaching a nascent reporter that culture is an ecosystem: art, commerce, ritual.

Two rooms, one week apart—how performance tells the truth and lies. The Elvis entry is a bravura scene report: Also sprach Zarathustra booms, limos roll in after the band starts “That’s All Right,” and the King works the stage with karate pantomime and crowd-teasing impersonations.

Then, for one song, “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” everything changes—eyes shut, focus sharpens, and Crowe witnesses a man reconnecting to the duty of song. He times it—47 minutes—and drives home stunned.

A week later, in a smaller hall, Derek and the Dominos play while Layla and Other Love Songs is only “two weeks old.” It’s an elemental crackle between audience and artist—the kind of night that convinces a skeptical schoolteacher mother that “the power of rock and roll” is real. These pages are the book’s thesis-in-action: context matters, and so does attention.

San Diego as laboratory—teachers, sailors, surfers, retirees. The memoir circles back to place. San Diego is the kind of tour stop where bands exhale; a city where pressure is off and parties begin. It’s also where Alice becomes a campus institution—Chicano Studies, a red blazer, bowler hat, a living room full of students at all hours, and the walls papered with aphorisms (her favorite: “Joy is the most infallible sign of the presence of God”).

When she invites César Chávez to class, he spots Cameron and says: “I hear you’re a writer.” From that moment the label fits; a vocation has been spoken aloud.

Bowie years—permission to be curious. The center of the book’s rock-journalism mosaic is David Bowie, who invites Crowe to “ask me whatever you want” and mean it.

These chapters are electric with mid-’70s Los Angeles: a yellow VW bug at 7 a.m., a post-studio drift from Cherokee through La Brea, the declaration “LA is my favorite museum,” and the way Bowie sees strip malls as installations. We get the cut-up method (“‘Audience’ is the title … the fragmentation is more eloquent than trying to stay linear”), the fresh persona of the Thin White Duke, and the swirl of paranoia around pools “where Satan lived.”

The portrait is affectionate and unsentimental: a brilliant artist seeking—music, persona, edge—on “a diet of milk, red peppers, and cocaine,” and a very young reporter learning to listen without judgment and to label his cassettes diligently each night.

Gregg Allman, Tom Petty, and the shift from page to set. Elsewhere, Crowe applies the same precise attention to other musicians—Gregg Allman’s boundaries, Ronnie Van Zant’s sparks of coming greatness—but the inflection point for his own life arrives in 1982. Riding a Winnebago with Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers to a desert video shoot, he watches Petty pick Elvis deep cuts (“‘(Marie’s the Name) His Latest Flame’”) and relive meeting Presley at age ten on the Follow That Dream set in Gainesville.

When Petty says, “Pick up the camera and shoot,” Crowe experiences the “elixir” of music-image-story fused: “It was like writing but without a pen … writing with my heart and a camera.” A chapter of journalism ends; the director’s life begins.

The private soundtrack—Cathy, the “ting,” and grief’s echo. Alongside the tour buses and studios, The Uncool is a family book. Crowe threads in a fairy-tale about a cedar-box fairy doll whose reassuring “ting” disappears and returns—an allegory that clicks into place when he writes, “In May of 1957, Cathy was only ten years away from the dark July when she left us.”

The music he loved—Beach Boys, Tremeloes, Joni—was first Cathy’s, and the book’s most tender pages insist that pop isn’t trivial when it binds siblings across time: “My music was her music. It was our ting.”

Return to the phone call—art, fear, and doing good. The framing device pays off: the stage is still calling, the musical still uncertain, and Alice’s nightly call becomes a ritual of courage and ethics. The memoir’s through-line isn’t “how I got famous.” It’s how a son kept trying to honor two voices—his mother’s aphorisms and his sister’s songs—while learning to hold up a mirror to artists without losing his own face in the reflection.

The Uncool’s main arguments

- Attention is love—and a method. Crowe shows how to watch a room: timestamps, the angle of a light, what’s being sold in the aisles, who’s speaking through whom. Elvis’s night is documented with scene-specific evidence (“Elvis had been onstage forty-seven minutes”), not feelings; then he freely feels—“For a handful of minutes, everything shifted”—when Elvis turns sincere. This is the book’s argument for reporterly empathy.

- Context reveals truth. A week apart, two concerts—theatric Elvis vs a hungry Clapton band with a brand-new album—teach that musical “truth” is variable, time-bound, and audience-dependent. “Layla and Other Love Songs was only two weeks old … by the next year … creative peak” compresses history to show how bounty becomes canon—and how fast it can all break up.

- Curiosity is a passport; decency is the visa. Bowie’s invitation—“Hold up a mirror”—and his willingness to let a very young journalist hang around for eighteen months prove that trust is earned by listening, not by performance. When Crowe writes about milk, red peppers, and cocaine, or about a pool “where Satan lived,” he keeps it observational, never cruel. The mirror works both ways: the subject gets seen; the writer becomes someone worth trusting.

- Mentors make artists—even when they’re your mother. Alice’s classroom, aphorisms, and the Chávez moment (“I hear you’re a writer”) name the vocation before the bylines or the Oscars. Her ethic—“doing good”—becomes the counter-myth to “cool.”

- Form mirrors life: mosaic over linear. The Bowie chapter itself argues for fragmentation as a modern narrative mode: “the fragmentation is more eloquent than trying to stay linear.” The memoir adopts that mosaic—short scenes, punchy closers, precise objects (a scarf, a Telecaster, a VW bug).

- Art changes the author. On the Winnebago, Petty’s mischief—“Pick up the camera and shoot”—pushes Crowe across a threshold: “It was like writing but without a pen … writing with my heart and a camera.” The book argues that work teaches you what you are.

The Uncool Themes

- Ethics over image. “The only true satisfaction comes from doing good.”

- The ordinary city as art. “LA is my favorite museum.”

- Process over persona. “‘Audience’ is the title … the fragmentation is more eloquent than trying to stay linear.”

- Sincerity flashes inside spectacle. “For a handful of minutes, everything shifted.”

- Loss as a tuning fork. “In May of 1957 … dark July when she left us … My music was her music. It was our ting.”

Key waypoints

- 1957 → “ten years away” from Cathy’s death; the family’s soundtrack (Beach Boys, Tremeloes, Joni) seeds Cameron’s ear.

- Late-1960s/early ’70s San Diego: surf culture crowds shows; Alice launches her San Diego City College chapter and later Chicano Studies.

- High-school years: Elvis San Diego show; Derek and the Dominos one week later; an origin story of scene reporting emerges.

- Mid-’70s: Bowie embeds (Young Americans → Station to Station era), studio days at Cherokee, VW mornings, and the “mirror” compact that births lasting interviews.

- November 1982: Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers “You Got Lucky” video; Crowe moves from pen to camera—a pivot toward filmmaking.

What the message The Uncool ultimately conveys

- Solves the myth of “cool.” Crowe keeps choosing grace over gossip, craft over swagger, and curiosity over cynicism. The Elvis chapter refuses to sneer at fans or idol; the Bowie chapters refuse to pathologize a genius in flux. The point isn’t that fame is hollow; it’s that attention—honest, exact attention—lets you see the human thing under the costume.

- Gives a practical blueprint for creative lives. The blueprint is almost embarrassingly simple: show up, listen, tape everything, ask real questions, help when you can, and do good (Alice’s rule). The proof is in the pivot: Petty’s “Pick up the camera” moment works because Crowe has earned the room’s trust by being prepared and present.

- Turns memory into primary source. Because Crowe names names, places, dates, and even song sequences, the memoir doubles as a field archive for late-’60s/’70s rock and early MTV-era video culture—recorded not as a historian looking back but as a participant with a reporter’s habits intact.

The Uncool quotes

- “The only true satisfaction comes from doing good.” — Alice Crowe.

- “You can ask me whatever you want … Hold up a mirror and show me what you see.” — David Bowie to Cameron Crowe.

- “LA is my favorite museum.” — Bowie.

- “‘Audience’ is the title … the fragmentation is more eloquent than trying to stay linear.” — Bowie on cut-up composition.

- “Elvis had been onstage forty-seven minutes.” — Crowe, timing the San Diego show.

- “Layla and Other Love Songs was only two weeks old … Now, this was a real rock concert.” — on Derek and the Dominos, a week after Elvis.

- “It was like writing but without a pen … writing with my heart and a camera.” — the Petty-sparked pivot.

- “My music was her music. It was our ting.” — on Cathy and the family’s soundtrack.

The Uncool braids a son’s ethics, a reporter’s exactness, and a filmmaker’s sense of scene into one long apprenticeship in paying attention—from Elvis’s 47-minute spectacle to Bowie’s cut-up dawns to Petty’s “shoot it now” dare—while never losing sight of the real chorus behind it all: a mother’s aphorisms and a sister’s mixtapes.

If you want, I can now expand this into a chapter-by-chapter digest (or a printable one-pager) with scene summaries and pull-quotes for each section.

4. The Uncool Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Crowe supports his reflections with granular reportage—a sense memory here, an exact timestamp there, verifiable names and venues everywhere. When he writes that “Elvis had been onstage forty-seven minutes”, it’s not an offhand quip; it functions like a fact anchor in a sea of screams and sequins.

This habit of precision surfaces again in portraits of other artists. A 1982 Winnebago ride with Tom Petty becomes an impromptu seminar on Presley movies, lovingly catalogued down to Toby Kwimper’s name in Follow That Dream, and contextualized by Petty’s childhood in Gainesville, Florida—details a reader can cross-check and a researcher can trust.

And then there’s David Bowie: Crowe reproduces the way lyrics emerge from cut-up scraps (“‘Audience’ is the title. Isn’t it a nice little tune?’), alongside Bowie’s provocation about art versus action on a hypothetical satellite TV show—a rare primary-source snapshot of how Bowie used interviews to test philosophical personas.

Does the memoir fulfill its stated purpose? While Crowe rarely states a thesis outright, the structure—short chapters often fronted by Alice’s aphorisms—enacts his credo that attitude shapes outcome. The opening epigraph, “The only true satisfaction comes from doing good,” lands not as platitude but as narrative pledge; you watch a son try to live up to it, whether he’s phoning his mother at 11 p.m. or letting an aging legend set the tempo in a trailer at a county fair.

In literary terms, the book’s reporterly eye marries a screenwriter’s sense of scene. Moments end on image or gesture—the handshake of Gregg Allman (“His voice was lower now, a box full of rocks”) turning into a refusal to look at a photograph of his late brother, a humane boundary the narrative honors.

The memoir contributes meaningfully to music history and media studies because it’s a primary source written by a practitioner who kept returning to the field. News coverage emphasizes that Crowe even reconvened many of the original players in recent interviews while structuring The Uncool as the first in a two-part project, underscoring its archival value.

5. Reception

Early notices describe the book as “deceptively breezy” yet emotionally frank about family, including the death of his sister Cathy—a through-line that gives the rock odyssey its ache.

Press coverage and interviews highlight the memoir’s twin arcs: the wonder of a kid invited into rooms where adults made culture, and the private griefs he carried there. People Magazine frames Crowe’s stated aim as a thank-you note to Cathy and his mother Alice, anchoring the book’s influence in the care ethic that shaped his films.

Independent outlets and the artist’s own site describe the launch in classic music-press terms: book tour dates, Stevie Nicks’s blurb, and publication positioning that compares the book to Patti Smith’s Just Kids—signals that The Uncool will circulate not only in film circles but in the canon of music-memoir literature.

AP’s advanced feature previewed the reportorial heft—from Bowie embeds to Zeppelin tour notes—helping explain why librarians, teachers, and researchers will assign this as first-person source material for the 1970s music ecosystem.

If there’s criticism to lodge, it’s the flip side of its strength: the mosaic form can feel like a mixtape—ecstatic transitions, occasional ellipses. But those gaps are honest to the era’s improvisational energy, and the book’s frequent scene-ending images create emotional continuity without spoon-feeding.

6. Comparison with similar other works

Crowe’s memoir pairs naturally with Patti Smith’s Just Kids (for friendship and art-making), Mikal Gilmore’s Shot in the Heart (for family shadows), and Lester Bangs’s collected writings (for a counterpoint voice from the same magazine culture).

Unlike Smith, who foregrounds poets and painters, Crowe writes as a reporter-screenwriter hybrid, moving from scribbled notes to cinematic beats. Unlike Bangs, he refuses sneer or nihilism; kindness and sense memory are his tools. And unlike traditional film memoirs, The Uncool treats movies as consequence, not origin—the film career is the remix of the teen reporter tapes.

Echoing reviewers, I’d also shelve this beside Moss Hart’s Act One—a comparison the publisher itself invokes—because both are origin stories about how hunger becomes craft and craft becomes a life.

7. Conclusion

If you read music biographies for the gossip, you’ll find some here, but it’s metabolized into civic feeling—how to be around greatness without becoming its casualty.

This isn’t just “the book behind Almost Famous.” It’s a manual for paying attention—to parents and siblings, to guitar vamps and backstage clocks, to the way a voice ages and still finds pitch.

Recommendation. Ideal for general readers who love cultural history with heart; essential for students of journalism and film, and for anyone who wants proof that curiosity plus decency can take you anywhere—sometimes all the way to the line where the house lights rise and the announcer says, “Elvis has left the building.”