The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann is more than a survival epic; it’s a razor-edged inquiry into how power and people manufacture truth, from the deck of a storm-tossed frigate to the court of public opinion (and yours and mine).

I’m writing this as a reader who devoured the book in one sitting, then went back to its notes, maps, and archival echoes; what follows is the most complete, human-voiced guide you’ll need to understand the story, the evidence, the arguments—and whether The Wager is for you.

If you’ve ever wondered how “civilization” holds (or breaks) when the food runs out and the cold bites deeper than fear, The Wager shows you—fact by brutal fact, story by weaponized story. According to the book’s prologue, when the wreck’s survivors first appeared, “the only impartial witness was the sun,” and even it watched men reduced to “bodies almost wasted to the bone.”

Grann’s message is that shipwreck survivors didn’t just fight hunger and weather—they fought over who gets to write reality, and those competing narratives could mean life, death, or the gallows.

Evidence snapshot: Thirty sailors reached Brazil in a makeshift boat after ~3,000 miles at sea, 283 days after the Wager was last seen; six months later a second skeletal trio arrived in Chile and accused the first group of mutiny, cannibalism, and murder—claims that culminated in Admiralty hearings and dueling published accounts.

The Wager is best for readers of narrative history who appreciate maps, primary sources, and the cold slap of moral ambiguity; not for those seeking a single “hero’s journey” or a tidy verdict where law, weather, hunger, and empire had none.

And because “HMS Wager mutiny” queries often seek context beyond the book, I’ve pulled corroborating sources on the wreck, the court-martial, and the cultural afterlife of the story (from BBC to TIME and Goodreads).

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann wad published in April 18, 2023 by Doubleday.

This is narrative nonfiction grounded in 18th-century naval history and imperial warfare; Grann, a longtime New Yorker staff writer known for Killers of the Flower Moon and The Lost City of Z, builds his account from logbooks, journals, and court documents—“archival debris,” as he calls it.

In his Author’s Note he writes, “I have…spent years combing through the archival debris…[and] tried to present all sides, leaving it to you to render the ultimate verdict.”

As the prologue and ensuing chapters make clear, this is not only a survival saga but a study in narrative power: the wrecked crew’s clashing stories determined reputations and sentences, while the empire’s official chroniclers sought to bend the record to its needs. “We all impose some coherence—some meaning—on the chaotic events of our existence,” Grann writes—an observation that sits at the book’s moral core.

2. Background

In the early 1740s, Britain’s war with Spain pushed the Royal Navy to project power into the Pacific, and one of the tools chosen was a hastily converted merchantman: the former East Indiaman Wager, launched in 1734 and bought into naval service in 1739 as a sixth-rate of 28 guns.

Among Anson’s ships was HMS Wager, whose human cargo included ill-recruited “invalids,” some carted aboard on stretchers, as chronicled by the Centurion’s chaplain, Reverend Walter.

Re-rigged and re-crewed, she joined Commodore George Anson’s ambitious squadron—six warships and two transports, together manned by roughly 1,854 men—tasked with harrying Spanish possessions and, if luck allowed, seizing a Manila galleon1.

Sailing in August–September 1740, Anson’s ships were hammered rounding Cape Horn; the Wager became separated and, after navigational error and foul weather drove her into the uncharted Gulf of Penas, she wrecked on 14 May 1741 on the coast now known as Wager Island in Chilean Patagonia.

The impact was compounded by a quirk of eighteenth-century naval law: officers’ commissions and sailors’ pay were tied to a particular ship. Once a ship was lost, authority and wages effectively lapsed—conditions that helped discipline collapse amid hunger, cold, and violence.

From that collapse emerged two protagonists whose rival testimonies would shape history’s memory. Captain David Cheap, elevated to acting command after the original captain died, tried to re-impose order but alienated much of his crew; months later Cheap and three officers, aided and then detained by Spanish authorities, eventually returned to Britain.

Gunner John Bulkeley, meanwhile, organized an escape in the refitted longboat Speedwell with dozens of men and, after a near-suicidal coastal run, brought about thirty survivors to Brazil—then rushed home to publish a bestselling account casting Cheap as the author of the disaster.

The wreck also jolted Spain: patrols scoured the Patagonian archipelago, and defensive projects followed, including the fortified settlement of Ancud (1767–68), to keep the British from establishing a foothold in the far south.

In Britain, Admiralty debates and later reforms clarified that naval command survives shipwreck—an institutional aftershock of the Wager’s ordeal that reverberates through David Grann’s retelling.

Cross-checked facts

- Embarkation: September 1740; ~250 aboard the Wager; secret mission to seize the Spanish galleon.

- Shipwreck: May 1741 (Patagonian coast; later “Wager Island”).

- Brazil landfall: 283 days after last sighting; ~3,000-mile voyage; ~81 launched; >50 died; ~30 arrived; within days, deaths continued.

- Chile landfall: six months later; 3 survivors; delirium recorded verbatim.

- Legal aftermath: Prison ship confinement at Spithead; court-martial machinery detailed; “mutiny that never was.”

- Publishing wars: Bulkeley & Cummins (1743); Walter/Anson (1748); ghostwriting by Benjamin Robins.

- Reception today: NYT bestseller; TIME Best of 2023; Goodreads Choice Award (History & Biography).

3. The Wager Summary

Highlighted points ✅ arguments ✅ themes ✅ lessons

✅ What happens: In September 1740, during Britain’s war with Spain, a Royal Navy squadron under Commodore George Anson sails from Portsmouth to raid Spanish interests and—if possible—capture a treasure galleon “known as ‘the prize of all the oceans’.”

Near Cape Horn, the sixth-rate Wager is blown off and wrecks in May 1741 on a barren Patagonian island; months later, one group of survivors reaches Brazil after a ~3,000-mile open-boat voyage, while another, arriving separately in Chile, accuses the first of mutiny—triggering pamphlet wars and an Admiralty court-martial back in London.

✅ Core argument: Grann insists that The Wager is not just a survival yarn; it’s a study of how desperate people—and empires—use stories to survive. Competing “faithful” vs. “imperfect” narratives became weapons that could save reputations or end lives on the gallows; he therefore presents “all sides,” leaving readers to deliver “history’s judgment.”

✅ Themes/lessons: (1) Fragility of order: Naval hierarchy can crumble into a “Hobbesian state” under starvation and cold—warring factions, murders, even cannibalism. (2) Empire’s hypocrisy: A mission framed as “civilization” turns on plunder and press-gang coercion. (3) Narrative power: Who controls the record—the gunner’s pamphlet, the captain’s allies, or Anson’s ghostwritten “official” history—controls memory. (4) Afterlives: The affair shapes Enlightenment debates and later sea literature (Byron, Melville, O’Brian) and even spurs Navy reforms.

Detailed summary

Setup: An imperial mission and the “wooden world”

Grann opens cinematically with a battered longboat—“above fifty feet long and ten feet wide”—drifting into a Brazilian inlet, stinking of seawater and death; thirty skeletal men announce they are castaways from His Majesty’s Ship Wager. The shock in London is immediate because the Wager, last seen in a hurricane off Cape Horn, was believed lost with all hands.

Rewinding, Part One (“The Wooden World”) drops us into Portsmouth’s chaos in 1740, where Anson—elevated to commodore despite thin patronage—prepares a small squadron for a secret strike across the Pacific.

The prize: a Manila galleon heavy with silver and Asian commodities. The squadron’s flagship Centurion is stout; the Wager, a refitted East Indiaman, is tubby and “unwieldy,” hastily transformed into a sixth-rate warship.

The “wooden world” is vivid: ships are high-tech for their time yet perishable (teredo worms, rot, fungus). Men are the most fragile component: disease ravages crews (“ship’s fever,” typhus), and the Navy fills ranks by press gangs and even five hundred “invalid” pensioners—some lifted aboard on stretchers.

The Wager’s company, a cross-section of Britain (gentlemen volunteers like 16-year-old John Byron; free Black seamen like John Duck; boys as young as six), coalesces into a brittle hierarchy.

At last, on 18 September 1740, the squadron catches a wind and clears the Channel—still dreaming of the “serpentine temptation” of a galleon that could make them rich.

Part Two: “Into the Storm”—Cape Horn breaks the fleet

Rounding Cape Horn in the austral winter proves catastrophic. The seas “routinely blow at gale force,” ice and uncharted coasts threaten, and the Wager—separated from Anson—stumbles towards disaster with sick, raw, and sometimes mutinous men. Grann uses logbooks to track the descent: on April 21, 1741, entries record death after death as water runs out and sails fail.

In May 1741 the Wager wrecks on a rocky island in the Golfo de Penas (later “Wager Island”), pitching the survivors into a landscape so barren that men live on mussels, birds, seaweed, and whatever they can scavenge. The class system initially holds—Articles of War, lashings, musters—but hunger, cold, and catastrophe corrode obedience.

Part Three: “Castaways”—order collapses, factions harden

“Faced with starvation and freezing temperatures,” the castaways build an outpost beneath Mount Misery and attempt to “re-create naval order.” Yet as food thefts, disease, and despair expand, so do tempers. Grann’s throughline is stark: Enlightenment ideals give way to a “Hobbesian state”—warring factions, marauders, abandonments, murders, and, for a few, cannibalism.

Key figures emerge: Captain David Cheap (centurion’s first lieutenant turned Wager captain after Kidd’s death), Gunner John Bulkeley (charismatic, pragmatic), Lieutenant Robert Baynes (indecisive), Midshipman John Byron (the future admiral, and grandfather of the poet).

Disputes over food, discipline, and the chance of rescue escalate, culminating in armed confrontations and the infamous shooting of the popular seaman Cozens, an episode that haunts Byron for life. (Grann later notes Byron’s memory of Cozens “gripped his hand after being shot.”)

Amid chaos, Bulkeley organizes the construction of a decked longboat (the Speedwell) and a plan to run north to Portuguese Brazil along the Chilean coast—an audacious, near-suicidal scheme given storms and Spanish patrols.

Eighty-one men eventually embark, “packed so tightly…they could barely move.” Over three and a half months, through “ice storms and earthquakes,” more than fifty die; about thirty survivors stagger into Brazil, one expiring as they make landfall.

The feat is one of the longest recorded castaway voyages. Locals can scarcely believe “human nature could possibly support the miseries that we have endured.”

Back on Wager Island, a smaller, stubborn group—loyal to Cheap or simply unable to sail—clings on. Months later a second, tiny boat—“a wooden dugout propelled by a sail stitched from the rags of blankets”—makes the Chilean coast with three survivors, “half naked and emaciated,” one so delirious he “had quite lost himself.” Their arrival sets the narrative trap.

Part Four: “Deliverance”—two rescues, two stories

Recovery in South America turns into a campaign to frame the past. The Brazil party, under Bulkeley’s influence, begins gathering support and polish for its version; the Chile group, attached to Captain Cheap, prepares a fierce counter-charge.

When both contingents finally reach England, months apart, the pamphlet war explodes.

Part Five: “Judgment”—pamphlets, court-martial, and the “version that won”

Back in London, the Admiralty confines key suspects on receiving ships at Spithead and convenes a court-martial. The stakes are existential: “If they failed to provide a convincing tale, they could be…hanged.” Both sides rush into print:

- Bulkeley & Cummins, in A Voyage to the South Seas (1743), cast themselves as dutiful seamen forced into resistance by Cheap’s tyranny.

- Captain Cheap’s allies work to rebut, asserting lawful authority never lapsed and branding Bulkeley the mutiny’s ringleader.

- The “official” story—A Voyage Round the World—emerges under Reverend Walter’s name but, as Grann shows, is substantially ghostwritten by mathematician Benjamin Robins, shaping public memory in Anson’s favor.

Grann underlines how narrative is power: pamphlets do not merely recount events; they manufacture them. He quotes castaways’ pledges to truth—“We stand or fall by the truth; if truth will not support us, nothing can”—and then shows how each side strategically withholds, exaggerates, or recruits eminent patrons.

The court, for its part, must decide not only individual guilt but whether command survives shipwreck—a legal ambiguity with life-or-death consequences.

Epilogue & aftermath: legacies on land and at sea

After the trials and print battles, the Wager story keeps echoing. Enlightenment thinkers (Rousseau, Montesquieu, Voltaire) and later Darwin and great sea novelists engage with its moral questions; Byron, long silent, finally publishes his own narrative in 1768, more candid now that Cheap is dead. (His later reputation, “Foul-Weather Jack,” and his grandson’s literary nods seal the affair’s place in cultural memory.)

Institutionally, Anson’s subsequent career as an admiral and, crucially, an administrator produces reforms—professionalizing the service, founding a permanent marine corps under Admiralty control, and addressing the chaotic manning/command structures that had plagued the Wager affair. He is later hailed as the “Father of the British Navy.” In other words, the wreck that nearly destroyed reputations becomes a lever for modernizing the force.

Chapter-by-chapter braid

- Author’s Note & Prologue: Grann discloses his method—years “combing through the archival debris,” refusing to “smooth out” contradictions—then stages the Brazil landfall and the Chile counter-arrival, framing the whole narrative as a clash of survival and storytelling.

- Part I (Chs. 1–3): Portraits of David Cheap (ambitious, brittle), John Byron (aristocratic novice), and John Bulkeley (craftsman-leader) against the logistical hell of war prep—rotten masts, typhus, press gangs, invalids, and a refitted East Indiaman renamed the Wager.

- Part II (Chs. 4–7): Dead reckoning to Cape Horn; storms peel ships apart; the Wager is isolated; logs turn elegiac as men die and water runs out.

- Part III (Chs. 8–16): Wreck; makeshift town; fraught encounters with Kawésqar (Nomads of the Sea); the rise of Mount Misery’s “lord”; extremes of hunger, discipline, and vengeance; Bulkeley’s Speedwell plan; the split; the open-boat odyssey to Brazil; Cheap’s remnant and a harrowing Chile landfall.

- Part IV (Chs. 17–20): “Port of God’s Mercy” (Brazil), the “Haunting” (guilt, loss), and “Day of Our Deliverance”—physical rescue gives way to narrative positioning.

- Part V (Chs. 21–26): A Literary Rebellion in Grub Street; The Docket and Court-Martial; and finally The Version That Won—with Anson’s camp’s official chronicle burnished by Benjamin Robins and cheap print reshaping truth.

Take-home lessons, plainly

- Stress tests character and systems. The Wager shows how quickly rigid institutions unravel when scarcity rises and legitimacy is contested; even “apostles of the Enlightenment” can descend into “depravity.”

- Truth is contested terrain. Competing “faithful” narratives become survival tools; the official history—polished by ghostwriters—can fix memory for generations.

- Catastrophe can catalyze reform. Anson’s later administrative career addresses very failures the Wager laid bare—manning, command ambiguity, professional standards—leaving a modernized Navy.

On Wager Island today, “several rotted wooden planks…from the skeletal frame” of an eighteenth-century hull still lie half-buried in an icy stream—mute fragments of a story that once convulsed an empire and still warns us how hunger, fear, and story decide who we become.

4. The Wager Analysis

Evaluation of content (does the evidence hold?): Grann’s opening tableau is so visual you can smell the salt and putrefaction: “Above fifty feet long and ten feet wide…patched together from scraps…thirty men were crammed onboard, their bodies almost wasted to the bone.” These lines are lifted directly from his reconstruction of the Brazil landfall.

He then toggles deftly between macro and micro: the War of Jenkins’ Ear (empire), the dockyard politics that made Anson’s rise unlikely (patronage), and the “invalids” foisted on the squadron (policy becomes mortality).

Anson, 42, “had been ‘round [the world], but never in it,’” a tart contemporary line Grann sources; more than color, it’s evidence of his method—braiding firsthand testimony, official records, and later commentary with clear attribution.

Does The Wager fulfill its purpose or contribute meaningfully? On the survival plot alone, yes: the Brazil party’s voyage—nearly 3,000 miles over about three and a half months—remains one of the longest castaway passages on record; the book supplies numbers (81 men setting off; “more than fifty” dying en route; only 29 standing at arrival) and then, crucially, the counter-narrative from Chile that brands them mutineers.

Grann embeds these in contemporaneous voices rather than narratorial fiat, which is essential given the trial that follows.

Grann’s portrait of moral collapse is not sensational but sourced: “There were warring factions…abandonments and murders. A few of the men succumbed to cannibalism.” The line is stark because the source material is stark; it also situates the episode in a longer history of Enlightenment ideals colliding with scarcity and fear.

The legal coda is equally meticulous. A marshal’s blunt prediction—“Hanged”—and Bulkeley’s riposte—“For God’s sake, for what? For not being drowned?”—reads like dialogue because it was; the Admiralty’s court-martial procedures, flexible in theory and haphazard in practice, are documented in the book’s legal chapters.

The book as argument about narrative control: Bulkeley and Cummins’s A Voyage to the South-Seas sells quickly, “in a plain maritime style,” shifting public opinion and forcing Captain Cheap and allies to mount counter-stories; later, Anson’s official chronicle emerges, ghostwritten in part by mathematician Benjamin Robins, with conspicuously little God for a clergyman’s book—another quiet example, Grann suggests, of institutional story-shaping.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

What gripped me: First, the prologue slam of images and numbers—30 men, a boat 50×10 feet, “wasted to the bone,” and a nation stunned 283 days after all hands were presumed lost—is narrative efficiency in service of truth.

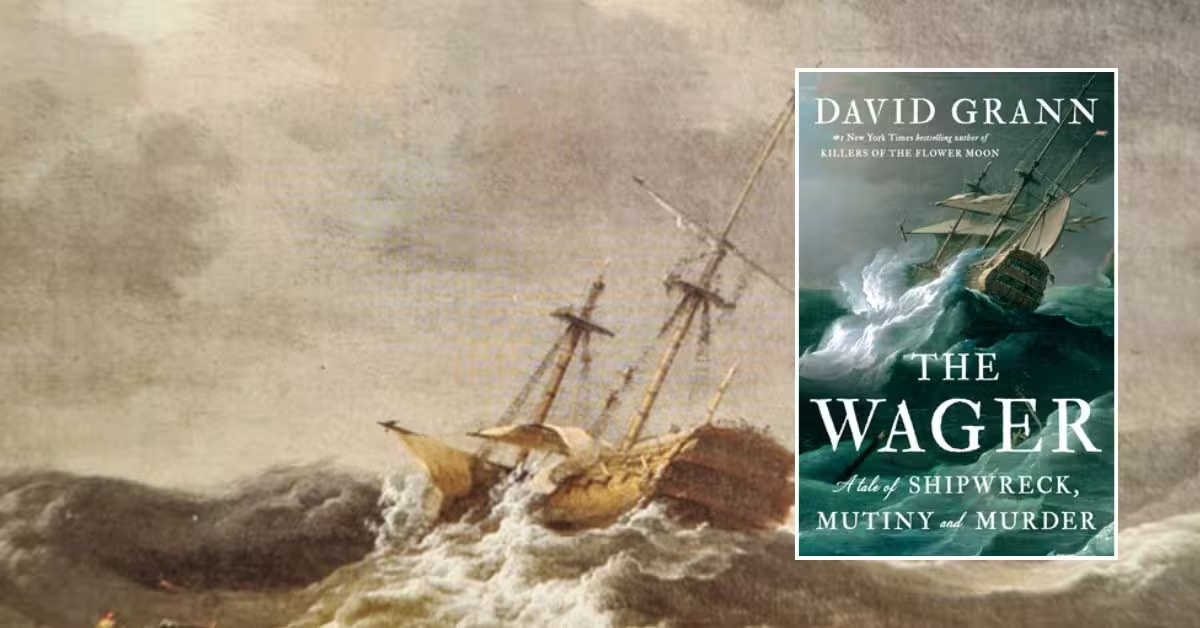

Second, the book’s maps and images (route, Cape Horn, location of the wreck; later engravings of the camp and Mount Misery) carry real informational weight; this isn’t “filler art” but a visual argument.

Third, the court-martial and publishing battles are written like a procedural without losing nuance; you feel how a “version that won” can erase depositions (“the mutiny that never was”) while consolidating imperial myth.

Where it stumbles (for me): By anchoring so strictly to what the sources permit, some emotional arcs remain understated, particularly for lesser-ranked sailors who left no extensive journals; this is the price of fidelity to 280-year-old fragments. (Grann signals this constraint plainly in his Author’s Note.)

The scurvy sections, essential and carefully sourced, can feel like a medical appendix to some readers, though their inclusion clarifies why discipline frayed and why “idiotism, lunacy, convulsions” entered the logbooks. I valued the rigor, but mileage may vary.

Net: The book brilliantly fulfills its own premise: lay out the evidence, reveal the pressures shaping each testimony, and let readers render “history’s judgment.” On that wager, Grann pays off.

6. Reception, criticism, and influence

Upon release, The Wager debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times hardcover nonfiction list and stayed on the list for over a year; it was named one of TIME’s 100 Must-Read Books of 2023 and won Goodreads Choice for History & Biography (reader-voted).

In the UK, the publisher notes The Wager was a Sunday Times No. 1 bestseller and longlisted for the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction.

BBC Radio 4 adapted The Wager as a Book of the Week in January 2024, with Luke Treadaway reading, a sign of mainstream cultural saturation beyond book pages.

Film rights: Apple and Imperative partnered with Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio on a planned adaptation (announced 2022–2023), though more recent trade coverage suggests Scorsese’s next film may be a different project; The Wager remains in development limbo common to prestige literary adaptations.

Critically, outlets emphasized both the propulsive craft and the historiographic spine: Kirkus praised the “brisk, absorbing history” and its imperial context; The Guardian called it “one of the finest nonfiction books I’ve ever read,” while The Washington Post admired the relentless plot but noted inevitable “narrative gaps” dictated by sources. (Convergence and divergence—a healthy reception.)

7. Comparison with similar works

If Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey–Maturin novels and Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim taught you to read the sea as a moral laboratory, The Wager is their nonfiction cousin—grimmer, better footnoted, and more suspicious of official memory.

Against Nathaniel Philbrick’s crowd-pleasers (In the Heart of the Sea), Grann runs colder and more forensic, yet achieves similar narrative drive by honoring contradictions—e.g., Reverend Walter’s official chronicle, likely shaped by Admiral Anson himself, downplays Cheap’s culpability and leans toward a doctrine that authority ended with the ship’s loss.

Readers who admire Andrea Pitzer’s archival sleuthing (Icebound) will feel at home in Grann’s notes and bibliography, while fans of imperial and maritime microhistory (e.g., The Terror’s historical underpinnings) will appreciate his attention to scurvy, provisioning, and the dull mechanics that produce catastrophes.

8. The Wager Quotes

“The only impartial witness was the sun.”

“Thirty men were crammed onboard, their bodies almost wasted to the bone.”

“We all impose some coherence—some meaning—on the chaotic events of our existence.”

“They were not heroes—they were mutineers.” (the Chile party’s charge)

“Money is a great temptation to people in our circumstances,” Bulkeley wrote as he rushed his narrative to press.

9. Conclusion

Read The Wager if you’re drawn to survival stories that refuse hero-worship, to court-martial transcripts where every comma is a weapon, to books that admit whole lives vanish between documents.

Skip it if you need tidy morals, unambiguous villains, or a single narrator you can marry your sympathy to; this ocean has more undertow than current.

If you teach history, ethics, or literature, it’s a model of how to stage evidence without pretending to omniscience; if you’re a general reader, it’s simply one of the great sea narratives of the last decade, and one that (to borrow a BBC phrasing) “sheds light on what happened when the Wager’s crew were stranded on an uninhabitable island thousands of miles from home.”

Final personal verdict

If you only read one sea book this year, read this one.

Because beyond storms and shoals, The Wager is a book about what people will do with a pen when a rope waits onshore.

Because, as Grann reminds us, even empires are editors—“the pages they tear out” matter as much as those they publish.

Because somewhere in those court-martial rooms and Grub Street deals is a mirror they made for us—and it still works.

10. Q&A

“Is The Wager true?” Yes—sourced to journals, logs, depositions, maps, and later scholarly compilations; the book quotes, cross-checks, and when necessary flags contradictions for the reader to judge.

“What is The Wager about, briefly?” A British warship wrecks near Cape Horn (1741); the survivors fracture into camps, a longboat party makes a death-ridden run to Brazil, and a second group lands in Chile accusing the first of mutiny and worse; back in England, trials and pamphlets decide whose version becomes “history.”

“Is there a Wager film?” Announced with Scorsese/DiCaprio/Apple attached; timeline currently fluid as Scorsese lines up other work; development status: active but unscheduled.

“Did the story shape ideas beyond the Navy?” Reports influenced Enlightenment thinkers and later Darwin and Melville, underscoring its reach beyond Admiralty walls.

Note

- The Manila galleon refers to the Spanish trading ships that linked the Philippines in the Spanish East Indies to Mexico, across the Pacific Ocean ↩︎