Troy (2004), a sweeping cinematic epic, brings to life the timeless tale of passion and war set against the backdrop of ancient Greece. At its heart lies the legendary love story of Paris and Helen—a fateful romance that ignites a conflict destined to reshape the world.

Paris, the impulsive and passionate prince of Troy, defies kingdoms and gods alike to steal away Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world and queen of Sparta. Their love, both forbidden and intoxicating, becomes the spark that plunges the mighty city of Troy into a decade-long siege, forever altering the lives of heroes, kings, and warriors on both sides.

Table of Contents

Introduction

“War is young men dying and old men talking,” Achilles famously grumbles in Troy (2004), a line that haunts me every time I revisit this sweeping, uneven yet undeniably magnetic cinematic spectacle.

Achilles, in Greek mythology, was the son of Peleus, king of the Myrmidons, and Thetis, a sea nymph. Known as the bravest, most handsome, and greatest warrior in Agamemnon’s army during the Trojan War, Achilles was raised in Phthia with his close companion Patroclus. Though Homer’s Iliad portrays Patroclus as a dear friend, later stories sometimes describe him as a relative or even a lover. Another famous legend—absent from Homer but widely told later—relates that Thetis dipped Achilles in the River Styx as a baby, making him invulnerable except for his heel, which she held during the immersion. This single vulnerable spot became his undoing—his famous “Achilles’ heel.”

Directed by Wolfgang Petersen and released in May 2004, Troy is a historical action epic loosely based on Homer’s Iliad and infused with cinematic flourishes that both dazzle and frustrate.

With a cast led by Brad Pitt as Achilles, Eric Bana as Hector, and Orlando Bloom as Paris, the film ambitiously condenses the decade-long Trojan War into just over two and a half hours of drama, romance, and blood-soaked battle. My overall impression? A beautifully crafted visual experience that struggles under the weight of its own ambition—a film that is both thrilling and deeply flawed, a reflection of its era’s blockbuster sensibilities.

Yet, there is something hauntingly human at its core—a desperate search for glory, meaning, and love amidst the chaos of war. As I explore its plot, performances, and artistry, I hope to unearth both its flaws and its triumphs, bringing a deeply personal, human perspective to this epic tale.

Plot Summary

In the grand tapestry of history and myth, few conflicts resonate as powerfully as the Trojan War—a war born from passion, betrayal, and a hunger for eternal glory. Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy (2004) endeavors to capture this mythic conflict, compressing the decade-long war into a cinematic experience that’s both sweeping and intimate, a kaleidoscope of clashing ideals and fragile humanity.

The film opens with an ominous overture: a vast Greek army led by King Agamemnon (Brian Cox) uniting the Greek city-states through sheer force of will and bloodshed. The world feels precariously balanced between the age of gods and the dawning of men—a world where honor and power intertwine, and every hero’s fate is as uncertain as the shifting wind.

At the center of this turmoil stands Achilles (Brad Pitt), Greece’s greatest warrior, who is as enigmatic as he is lethal. Achilles fights for Agamemnon not out of loyalty but for the promise of immortal glory—a human yearning that both elevates and damns him. His relationship with Agamemnon is fraught, their mutual disdain simmering beneath the thin veneer of unity.

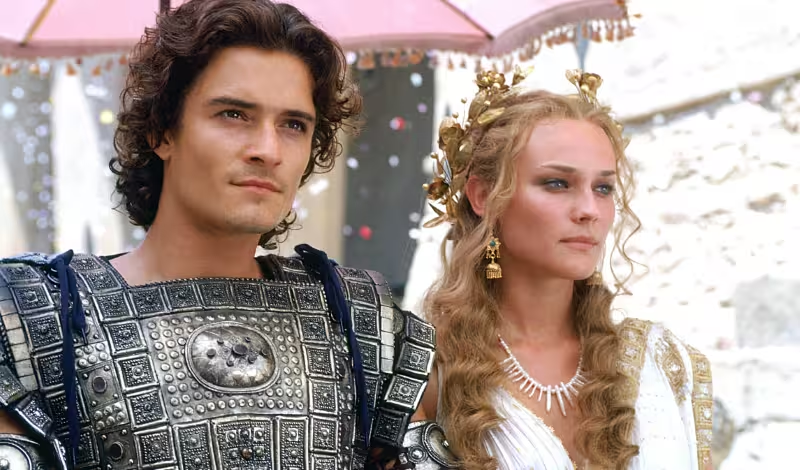

Meanwhile, in the kingdom of Troy, hope briefly flickers as peace talks between Troy and Sparta unfold. Prince Hector (Eric Bana), the embodiment of duty and nobility, and his brother Paris (Orlando Bloom), a reckless romantic, seek to secure peace with King Menelaus (Brendan Gleeson). Yet, fate intervenes in the form of love—or perhaps lust—when Paris and Queen Helen (Diane Kruger) fall for each other. Their secret passion ignites a fire that will consume kingdoms. Paris spirits Helen away to Troy, setting in motion the gears of war that will grind friend and foe alike into dust.

Agamemnon, seeing an opportunity for conquest under the guise of familial duty, rallies the Greeks to sail for Troy, with Achilles reluctantly in tow. From the first moment the Greek army lands on Trojan shores, the film plunges us into a maelstrom of violence and ambition. Achilles, ever the iconoclast, storms the beaches with his Myrmidons, carving a bloody path through Troy’s defenders, establishing the Greeks as an indomitable force—and himself as a living legend.

Inside the walled city, King Priam (Peter O’Toole) greets Helen with the grace of a man burdened by destiny. He knows that Troy’s fate now hangs in the balance, and that Hector must lead his people through the crucible that awaits. Hector’s sense of honor and duty is palpable; he bears the weight of his kingdom on his shoulders, a burden that threatens to crush him with every passing day.

The film takes time to explore the relationship between Achilles and Briseis (Rose Byrne), a captured Trojan priestess who becomes a pawn in the war’s bloody game. When Agamemnon cruelly takes Briseis from Achilles to assert his dominance, the rift between hero and king widens. Achilles withdraws from battle in a move reminiscent of Homer’s epic—a decision that leaves the Greek army vulnerable and the Trojan spirit emboldened.

The story’s beating heart is the tension between personal desire and duty. Paris’s impulsive love for Helen brings ruin; Hector’s loyalty to his family and country forces him into battles he cannot win. Achilles, despite his godlike prowess, is as vulnerable to love as any man, and his relationship with Briseis humanizes him, casting shadows of doubt across his seemingly unassailable confidence.

One of the film’s most powerful moments unfolds when Paris challenges Menelaus to a duel, hoping to end the war with a single stroke. The duel is raw, brutal, and dripping with the weight of honor and pride. Yet, even here, honor proves to be a fragile shield. Paris is wounded, but Hector intervenes to save his brother, violating the duel’s sacred code and setting off a chain reaction of vengeance.

In the chaos that follows, the film delivers spectacle with staggering scale: a cacophony of clashing swords, flaming arrows, and the cries of the dying. The siege of Troy becomes a crucible where humanity’s noblest and darkest impulses collide. Heroes rise and fall; faith in gods and men alike falters.

Patroclus (Garrett Hedlund), Achilles’ beloved cousin and protégé, disguises himself in Achilles’ armor to rally the Greek forces. His death at Hector’s hands is a tragedy that shatters both Achilles’ fragile detachment and Hector’s sense of honor. It is a moment that feels deeply human—a reminder that even in myth, grief binds us all.

Achilles’ rage erupts in a storm of vengeance. His duel with Hector outside the gates of Troy is both brutal and poetic, an elegy for a civilization’s dying breath. Hector fights with every ounce of his strength, but he cannot withstand Achilles’ wrath. His death is a profound loss, not just for Troy but for humanity’s collective sense of dignity. Achilles drags Hector’s lifeless body through the dirt—a visceral image that captures the dehumanizing toll of war.

Yet in the darkness, a spark of humanity remains. Priam, in one of the film’s most affecting scenes, sneaks into the Greek camp to beg Achilles for his son’s body. Peter O’Toole’s performance is heartbreaking, his aged king’s voice trembling with grief and dignity. Achilles, moved by Priam’s humility and sorrow, relents, allowing Hector’s funeral rites to proceed. This gesture—small in the face of so much bloodshed—feels like a flicker of redemption.

The film hurtles toward its inevitable conclusion: the Greeks’ infamous trick of the wooden horse. The Trojans, desperate for hope, drag it inside their walls, sealing their own fate. At nightfall, Greek soldiers pour from the horse’s belly like a plague, opening the gates to the waiting army. The sack of Troy is merciless: men slaughtered, women dragged away, and fires consuming everything. The city that had once been a symbol of human resilience now crumbles into dust.

In a final, tragic twist, Paris shoots Achilles with an arrow to the heel—his only vulnerability. Achilles dies in Briseis’ arms, their love reduced to ashes in the aftermath of war. As Troy burns, the film closes with the survivors fleeing into the night—a new beginning born from a sea of grief and ruin.

Analysis

1. Direction and Cinematography

Wolfgang Petersen’s direction in Troy is a masterclass in orchestrating chaos—a visual spectacle that attempts to balance grand-scale battles with the intimate struggles of its characters. His vision is evident from the film’s opening shots, where we see vast Greek armies mustering on the shores of Troy, each frame dripping with a sense of ancient grandeur. Yet, amidst this grandeur, Petersen’s direction is sometimes at odds with the emotional core of the story.

Petersen’s approach leans heavily on visual storytelling, emphasizing the physicality of war through elaborate set pieces and visceral combat sequences. Roger Pratt’s cinematography, with its rich, sun-baked hues and sweeping shots of the Mediterranean landscapes, immerses us in a world that feels both mythic and tangible. The film’s palette, dominated by dusty ochres and blazing golds, evokes the sun-scorched plains of ancient Troy, lending authenticity to the narrative.

However, while the visuals are undeniably striking, they sometimes overshadow the characters’ emotional arcs. Petersen occasionally sacrifices subtlety for spectacle, opting for wide shots of armies clashing rather than lingering on the human faces within the maelstrom. This choice, while thrilling, can leave the viewer yearning for deeper insight into the emotional toll of war.

Still, Petersen’s commitment to scale cannot be denied. The battle sequences—particularly the duel between Hector and Achilles—are choreographed with an almost balletic precision, capturing both the brutality and the tragic beauty of combat. These scenes resonate because they remind us that even in the chaos of war, moments of human connection and vulnerability can still shine through.

2. Acting Performances

The ensemble cast of Troy delivers performances that range from the transcendent to the underwhelming, a testament to both the film’s ambition and its uneven execution. At the center of it all is Brad Pitt as Achilles—a performance that has divided audiences and critics alike. Pitt’s Achilles is a study in contradictions: a man driven by ego and glory, yet vulnerable to the stirrings of love and grief. Pitt brings a modern intensity to the role, imbuing Achilles with a brooding charisma that commands attention even in the film’s quieter moments.

Eric Bana’s portrayal of Hector, by contrast, is a revelation. Bana captures Hector’s nobility, his sense of duty, and the quiet desperation that comes from knowing his city’s fate rests on his shoulders. His chemistry with Peter O’Toole’s Priam is particularly poignant, grounding the film in a father-son dynamic that feels achingly real.

Orlando Bloom’s Paris, on the other hand, struggles to transcend the script’s limitations. While Bloom embodies the youthful impulsiveness that defines Paris, his performance occasionally veers into melodrama, leaving the character feeling somewhat one-dimensional. Diane Kruger’s Helen fares slightly better, capturing both the allure and the tragedy of a woman caught in a conflict far larger than herself.

Supporting performances by Brian Cox as Agamemnon and Sean Bean as Odysseus add gravitas to the film’s political intrigue. Cox’s Agamemnon is a study in ruthless ambition, while Bean’s Odysseus brings a wry pragmatism that serves as a counterpoint to the film’s more mythic elements.

3. Script and Dialogue

David Benioff’s screenplay for Troy is an ambitious undertaking—condensing the sprawling Trojan War into a two-and-a-half-hour epic while attempting to humanize its legendary figures. At its best, the script shines in its quieter moments, such as Priam’s plea to Achilles for Hector’s body—a scene that captures the essence of humanity amidst the ruins of war.

However, the screenplay sometimes falters under the weight of its own ambition. The decision to compress a decade-long conflict into a matter of weeks robs the story of some of its epic sweep, and character arcs can feel rushed or underdeveloped. The dialogue, too, vacillates between poetic and pedestrian. Lines like “War is young men dying and old men talking” resonate with bitter truth, while others (“Imagine a king who fights his own battles. Wouldn’t that be a sight?”) land with the subtlety of a war hammer.

Benioff’s decision to strip away most references to the gods—a deliberate move to ground the story in human motivations—yields mixed results. While it makes the characters’ choices feel more personal and relatable, it also strips the narrative of the mythic resonance that made Homer’s Iliad so enduring. The film becomes a study in human frailty rather than a meditation on fate and divine justice.

4. Music and Sound Design

James Horner’s score for Troy is a triumph of atmosphere over subtlety—a sweeping, percussive soundtrack that infuses the film with a sense of grandeur and tragedy. Horner’s use of traditional Eastern Mediterranean instruments, combined with Carovska’s haunting vocals, transports us to an ancient world teetering on the edge of collapse.

The music often serves as an emotional anchor, heightening the tension during battle sequences and lending a mournful beauty to the film’s quieter moments. The end credits song “Remember Me,” performed by Josh Groban, is a bittersweet coda that encapsulates the film’s themes of love, loss, and the human desire for immortality.

Sound design plays a crucial role in immersing the audience in the chaos of war. The clang of swords, the whistling of arrows, and the roar of the battlefield are rendered with visceral intensity, ensuring that every clash feels immediate and real. However, some critics have noted that Horner’s score, while powerful, can at times overwhelm the on-screen action, making it difficult for quieter character moments to breathe.

5. Themes and Messages

At its core, Troy is a meditation on the futility of war, the hunger for glory, and the fragile beauty of human connection. The film grapples with the tension between the pursuit of immortality through heroism and the simple, enduring bonds of love and family. Achilles’ journey—from arrogant warrior to a man capable of empathy—embodies this struggle, highlighting the universal human desire for meaning beyond the battlefield.

The film also examines the collateral damage of ambition. Agamemnon’s lust for power consumes not only Troy but his own men, reminding us that even the mightiest empires crumble under the weight of hubris. Hector’s sacrifice is a testament to the tragic nobility of those who fight not for glory but for the people they love.

In stripping away the intervention of gods, Petersen and Benioff force us to confront the raw humanity at the heart of the legend. The choices made by Achilles, Hector, and even Paris are driven by deeply human impulses—love, fear, pride, and desperation. This human perspective makes Troy resonate as more than just a historical epic; it becomes a mirror reflecting our own struggles with duty, desire, and destiny.

Comparison

When considering Troy (2004) alongside other epic historical dramas, such as Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) or Oliver Stone’s Alexander (2004), one cannot ignore the distinct approach each film takes in balancing spectacle with substance. Where Gladiator found a near-perfect harmony between its protagonist’s personal journey and the grandeur of ancient Rome, Troy often leans more heavily into the spectacle than the introspection.

Ridley Scott’s use of shadow and intimacy in Gladiator allows for a visceral connection to Maximus’ tragedy, whereas Petersen’s sweeping wide shots sometimes render Achilles and Hector more as icons than fully realized men. In contrast, Alexander—though less successful critically—embraces a more ambitious, almost operatic tone, with Stone delving deep into the psychological complexities of his protagonist. Troy situates itself somewhere between these two poles: striving for psychological depth but often getting lost in the bombast of its own battles.

Compared to Petersen’s own earlier work (Das Boot, 1981), Troy feels more commercially driven, with its focus on star power and visual spectacle sometimes undermining its emotional core. Yet, in its best moments—such as Priam’s entreaty to Achilles or Hector’s farewell to Andromache—the film rises above its limitations, offering glimpses of the tragic humanity that made the legend timeless.

Audience Appeal/Reception

Who is Troy (2004) for? Primarily, it’s a film that appeals to lovers of historical epics, those who revel in the clang of swords, the sweep of vast armies, and the grand scale of myth. The film’s action sequences, handsome production design, and star-studded cast draw casual viewers seeking an immersive experience.

Yet, its uneven storytelling and lack of adherence to Homer’s Iliad may frustrate purists and scholars who yearn for a more faithful adaptation. As BBC observed, Troy “excels in entertainment value but struggles to capture the poetic soul of its source material” (BBC). Even so, the film found significant box office success—grossing nearly \$500 million worldwide—proving that its blend of spectacle and star power had undeniable mass appeal.

For cinephiles seeking nuanced character studies or profound philosophical insights, Troy may leave them wanting. However, for those who appreciate sweeping visuals, larger-than-life heroes, and timeless tales of love and war, the film offers a satisfying—if imperfect—cinematic journey.

Personal Insight

As I reflect on Troy (2004) from the vantage point of our own turbulent times, I can’t help but see echoes of humanity’s perennial struggles: the allure of glory, the sacrifice of loved ones, the cost of ambition. Watching Hector’s farewell to Andromache is a painful reminder of every soldier who has kissed their family goodbye, uncertain if they will return.

Achilles’ yearning for immortality—his refusal to be just another name lost to history—mirrors our own modern obsessions with legacy and digital permanence. The film’s final image of a city in flames, of a civilization laid low by hubris and heartbreak, feels hauntingly prescient in a world grappling with its own cycles of violence and collapse.

In the end, Troy is a reminder that no matter how far we think we’ve come, the human heart still beats to the same rhythms: love, rage, fear, and the desperate hope that something of us will endure beyond the ashes.

Quotations

- “War is young men dying and old men talking.” — Achilles

- “Imagine a king who fights his own battles. Wouldn’t that be a sight?” — Achilles

- “I’ve fought many wars in my time. Some for country, some for kings. But I’ve never fought for myself.” — Achilles

- “Let no man forget how menacing we are; we are lions!” — Achilles

- “Even the mightiest of men, even the greatest of heroes, can be felled by a single arrow.” — Priam

✅ Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Stunning visuals that bring ancient Troy to life

- Gripping battle sequences with visceral realism

- Strong performances by Eric Bana and Peter O’Toole

- James Horner’s sweeping score adds emotional weight

- Thought-provoking human themes about glory, duty, and mortality

Cons:

- Uneven character development, especially for secondary roles

- Dialogue occasionally feels stilted or melodramatic

- Rushed pacing due to condensing a decade-long war into weeks

- Overemphasis on spectacle at the expense of emotional depth

Conclusion

In the grand tradition of sword-and-sandal epics, Troy (2004) carves its place as a visually arresting, if imperfect, retelling of Homer’s immortal tale. It dazzles with its scale, its star power, and its commitment to spectacle, yet it sometimes stumbles in capturing the profound humanity at the heart of the legend.

Brad Pitt’s Achilles may not be the definitive hero, but his struggle with glory and mortality mirrors our own deepest fears and desires. Eric Bana’s Hector reminds us that heroism often comes not from grand gestures but from small acts of love and sacrifice. James Horner’s score swells with the weight of history, anchoring the film’s greatest triumphs and tragedies.

In the end, Troy invites us to gaze upon a world both ancient and achingly familiar, to see ourselves in the clash of empires and the tears of widows. It may not achieve cinematic immortality, but like Achilles, it leaves a mark on the heart—a reminder that even in our grandest myths, it is the human story that endures.

Rating

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ (4/5 stars)