Unfettered by John Fetterman isn’t just a political memoir; it’s a manual for surviving public shame, private despair, and a broken justice system—without losing your voice.

Unfettered argues that telling the unvarnished truth about mental health, power, and punishment is not weakness but leverage—personally healing and politically clarifying.

Depression lies, institutions calcify, and politics rewards performative outrage; Unfettered shows how one person clawed back meaning—and why reform and candor can coexist.

Fetterman’s point is plain: depression is a disease, second chances matter, and performative politics can’t stand up to lived facts, whether they’re embroidered on his hoodie or carved into the Pennsylvania code.

Fetterman documents clinical symptoms, hospitalization at Walter Reed for major depressive disorder, and the specific trigger-thought loop that led him to the Great Allegheny Passage in suicidal ideation.

He details Board of Pardons decisions, the legal architecture of felony murder in Pennsylvania (mandatory life without parole), and population-level disparities—with figures by year and county.

External records corroborate the September 27, 2023 Senate dress code vote and his 2022 election results (2,751,012 votes; 51.17%), while national outlets document his Feb. 2023 hospitalization.

Brief introduction focusing the keywords

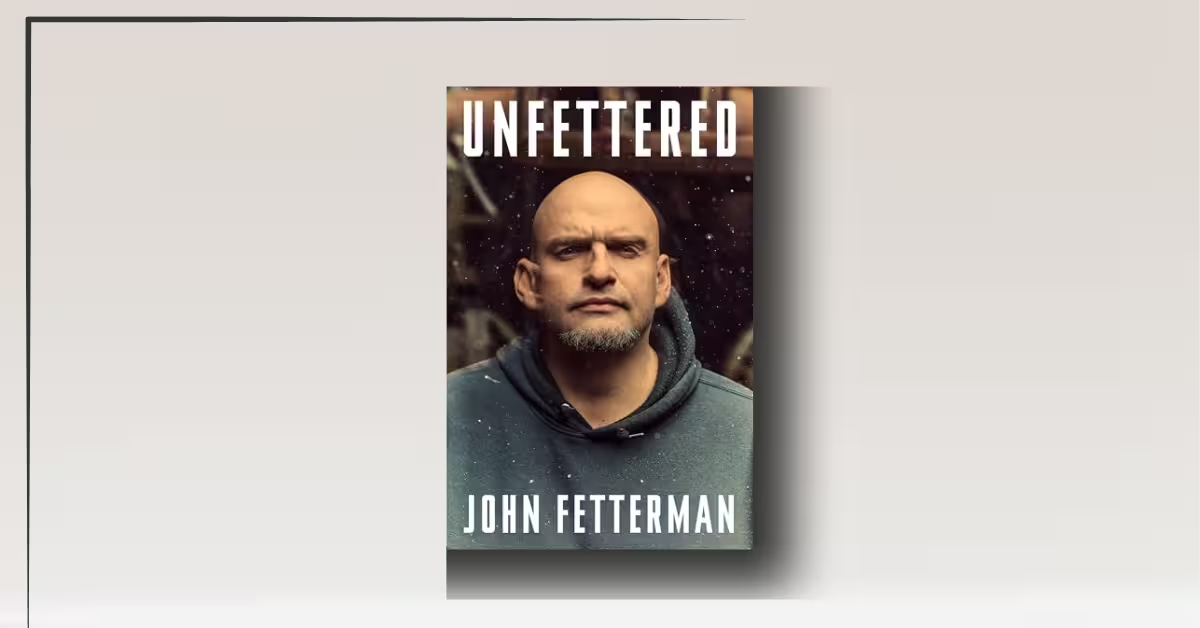

Unfettered by John Fetterman is a contemporary political memoir that doubles as a survival narrative about depression, a tract on criminal justice reform (especially felony murder in Pennsylvania), and a firsthand report from the Senate dress code wars—keywords that real readers search because they’re the pressure points of modern civic life.

And because Unfettered came out with a major publisher in 2025 (ISBN 9780593799826), it’s already shaping searches and debates beyond political news cycles.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Unfettered by John Fetterman, U.S. senator from Pennsylvania, is a 240-page memoir published in 2025 (ISBN 9780593799826).

Genre-wise, it’s political nonfiction threaded with mental-health reportage and criminal-justice advocacy; Fetterman served as Braddock mayor, Pennsylvania lieutenant governor (and Board of Pardons chair), then won the 2022 Senate race (51.17%).

The throughline is explicit from the prologue and author’s note: to pay forward survival lessons—“Depression lies to you”—while explaining why second chances in law and life are not a luxury but an obligation.

Quotation (book): “Depression lies to you. It will try to convince you that taking your life is the solution.”

2. Background

Unfettered begins with the Great Allegheny Passage and a blue bridge near the old Carrie Furnace, anchoring his suicidal ideation in a geography of industrial collapse—and in the private echo chamber of self-contempt that accompanies major depression.

Public reporting places his inpatient treatment at Walter Reed in mid-February 2023, with six weeks of care before returning to the Senate in April; clinical coverage underscores how common post-stroke depression is.

3. Unfettered Summary

Unfettered is John Fetterman’s braided narrative of mental-health crisis and political reform—how a suicidal spiral after a stroke collided with his years chairing Pennsylvania’s Board of Pardons and a very public fight over what counts as “decorum,” and why telling the hard truth is the only workable politics left.

Fetterman opens with why he writes: not for image burnishing but to leave a usable record—“an authentic advocate”—of surviving depression while governing in a performative age. He frames Washington as a place where people “lose their [minds] over the dress code” while ignoring structural problems, then rewinds to explain why suits always felt like armor that didn’t fit.

Unfettered’s first movement walks through the 2023 shorts-and-hoodie furor and the Senate’s reaction—Schumer’s brief relaxation of tradition and, on September 27, 2023, a unanimous resolution reinstating a formal dress code (briefly nicknamed the SHORTS Act)—as a primer on symbolism versus substance in American politics.

From there, he pivots to the personal engine of the book: the stroke, the shattering onset of major depression, and his voluntary inpatient treatment at Walter Reed in early 2023.

He details the cascade—medication interactions, plummeting blood pressure, cognitive fog, and the shame spiral that followed—then strips away any romanticism: he wasn’t in a VIP psych ward; he was in the Traumatic Brain Injury Unit, seen daily by a team of cardiologists, neurologists, and psychiatrists, and learning—slowly—that “depression is treatable.”

The national press frenzy becomes a background hum to the real work: therapy several times a week, re-hydration, a healing-garden routine, and the hard restart of speaking aloud and reading to rebuild fluency and confidence.

He notes that a typical inpatient stay for clinical depression runs about six days, but he remained more than forty—a number chosen to ensure both his mind and heart were stable for a return to the Senate.

While that medical arc supplies the human stakes, the policy arc explains the fights that made him controversial long before shorts. As lieutenant governor, Fetterman chaired the five-member Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, where commutations of life sentences (especially for felony murder) require a unanimous 5–0 vote—an extreme threshold imposed after the Reginald McFadden debacle of the 1990s.

He reconstructs how McFadden’s post-release murders and the politics of fear (amplified nationally by Willie Horton ads) choked off mercy statewide: after Gov. Robert Casey left office, commutations for lifers dwindled to six total, compared with 251 granted by Gov. Milton Shapp in the 1970s.

That context is essential to understanding later clashes with then–Attorney General Josh Shapiro, who sat on the same board and whose caution, in Fetterman’s telling, often vetoed cases that had support from wardens, prosecutors, and the Department of Corrections.

The statistics are the book’s cold center. Pennsylvania mandates life without parole for second-degree (felony) murder—even when the defendant didn’t kill anyone, had no weapon, and could not have foreseen a co-felon’s violence.

As of 2024, 1,131 people in the state were serving life for felony murder; 8,242 were serving life overall (second-highest in the world), two-thirds without any chance at parole except by commutation. The racial skew is stark: Black Pennsylvanians are 17× more likely than whites to be imprisoned for felony murder; 71% of people serving life for felony murder are Black, including 83% in Allegheny County and 87% in Philadelphia.

Unfettered then zooms into the human files behind those numbers—people Fetterman believed no longer posed a threat after decades served, whose petitions had institutional support, and whose denials or delays (he argues) reflected optics more than facts.

That conflict crescendos in the chapters that trace the Horton brothers (Reid and Wyatt) and other high-profile petitions.

We watch live-streamed hearings (pandemic era), “under advisement” maneuvers that slow-walk cases, and an infamous hot-mic moment when Fetterman—furious at another delay—calls Shapiro a “f—ing asshole.”

The emotional temperature is high, but the procedural lesson is clearer still: under a unanimity rule, one “no” is a life sentence. He juxtaposes a rare breakthrough—September 13, 2019, when nine lifers were recommended for commutation in a single day (more than the previous 24 years combined)—with a later December 20, 2019 docket where only two of 15 cases advanced, and his reading-glasses hit the floor in frustration.

The uneasy truth he presses on the reader: politicians “never lose votes by refusing to give a prisoner a second chance,” and that incentive structure deforms justice.

Returning to Washington, the dress-code saga becomes a parable: forty-six senators can rally overnight to police clothing, he notes, even as bipartisan coalitions struggle to muster courage on clemency, sentencing, or mental-health access.

His workaround—vote by stepping just inside the chamber door in standard clothes, then ducking back out—reads both comic and cutting, a physical illustration of a broader thesis: “A suit doesn’t mean anything… the seditionists wore suits.”

The closing movement knits together his family’s experience of the media storm (Gisele taking the kids to Niagara Falls to escape cameras for two days; the “worst wife in America” pile-on) with his own non-negotiable message to readers: don’t confuse shame with responsibility; get help. If there’s one sentence he wants repeated, it’s simple: “Depression is a disease… and it is eminently treatable.”

Highlighted takeaways

- Aug. 15, 1969 — Birth in Reading, PA. Early body-image discomfort and an aversion to suits seed later symbolism; the memoir repeatedly links attire to belonging and anxiety.

- Board of Pardons mandate (2019–2022) — Role & rules. As lieutenant governor, Fetterman chairs the five-member board; commutations for lifers require unanimity (5–0) after the McFadden case changed the law.

- Felony-murder architecture (Pennsylvania). Statute imposes mandatory life without parole for second-degree murder; the person need not be the killer, armed, nor intend a killing. This creates extreme sentencing outcomes and carries a racial skew (Black imprisonment 17× higher for felony murder; 71% of felony-murder lifers are Black).

- Sept. 13, 2019 — A rare mercy surge. Nine lifers recommended for commutation in a single day—more than the previous 24 years combined—signed off by Gov. Tom Wolf.

- Dec. 20, 2019 — The “Shapiro Affair.” Only two of 15 cases advance; Fetterman describes the soul-crushing ritual of pleading for freedom before strangers and the anger that boiled over.

- Case studies (2019–2020) — What a single “no” does.

• Pedro Reynoso: 13 alibi witnesses, model prisoner, 25 years served—Denied.

• Francisco Mojica, Jr.: Shooter brother served 6–12 years; Francisco got life—Denied.

• Reid & Wyatt Horton: Carjacking with no intent to kill; victim died later of a heart attack—Denied; reconsideration delayed; hot-mic slur at Shapiro; father pleads for sons’ release before he dies. - The McFadden & Horton (Willie) hangovers (1990s–1988). McFadden’s killings after clemency torpedoed Mark Singel’s gubernatorial run and hardened Pennsylvania law; nationally, the Horton ad showed how fear can dominate policy for decades. Result: mercy became politically radioactive.

- Numbers to remember (as of 2024).

• 1,131 people serving life for felony murder.

• 8,242 serving life total; ⅔ LWOP unless commuted.

• 17× higher felony-murder incarceration for Black Pennsylvanians; 83% of Allegheny, 87% of Philadelphia felony-murder lifers are Black. - Sept. 27, 2023 — Senate dress-code resolution. After Schumer’s informal relaxation, the Senate votes unanimously to formalize business attire; the SHORTS moniker is dropped after Fetterman’s office objects. He keeps voting by stepping just inside the door.

- Feb.–Apr. 2023 — Walter Reed inpatient arc. Depression intertwined with post-stroke treatment; he learns to name symptoms, accept multi-specialty care, and say publicly: “depression is treatable.” A typical six-day stay turns into >40 days to ensure stability.

- Family & media. Gisele shields the kids with a short trip to Niagara Falls while cameras swarm their home; headlines and social-media pile-ons mischaracterize her choice; the lesson for readers is explicit: seeking help is courage, not scandal.

- Governing thesis. “The bureaucracy… is the evil empire,” he writes; unless you “sharpen your elbows,” nothing moves. Mercy is hard, optics are easy, and institutions will default to inaction unless pushed.

What the chapters add up to

1) Honesty beats optics. The dress-code saga teaches that the Senate can act fast on aesthetics while moving glacially on substance; he refuses to equate formalwear with integrity—“A suit doesn’t mean anything”—and votes in his own skin. The upshot: use your energy where it frees people, not where it flatters institutions.

2) Mercy requires structure, not vibes. Pennsylvania’s unanimity rule weaponizes caution; a single dissenter can lock a case for life. When nine lifers clear the board in one day after 24 barren years, Unfettered demonstrates that process—not personality alone—decides who gets out. If you want more mercy, change the rules that punish it.

3) Data clarifies courage. The felony-murder numbers (1,131 lifers; 17× racial disparity) are not rhetorical flourishes; they are the evidentiary backbone for an argument about proportionality and risk. He owns the fear—“your biggest fear is [a released person] committing a violent crime”—but insists good governance isn’t the absence of risk; it’s the management of it with facts.

4) Depression lies; treatment works. Fetterman shows how shame and physiological aftershocks feed each other, and how admitting yourself can reset the cycle. The “>40-day” inpatient choice models leadership as boundary-setting, not stoicism. Message to readers: ask for help early and loudly.

5) Politics is a human contact sport. The Shapiro chapters aren’t scored as heroes vs. villains so much as opposing philosophies of risk under a unanimity constraint. The book’s most unsparing passages are aimed not at one man but at a system where optics punish mercy and reward delay. If incentives don’t change, outcomes won’t, either.

Selective Quotes

- “Depression is… eminently treatable.”

- “A suit doesn’t mean anything.”

- “The bureaucracy in government is the evil empire.”

- “When you’re on the Board of Pardons, your biggest fear [is a released person harming someone].”

- “A unanimous vote of 5–0 [is required for commutations].”

4. Unfettered Analysis

Fetterman’s evidence is both intimate (symptom checklists; domestic fallout; the bench across from the bridge) and institutional (vote counts; legal statutes; racialized impact metrics of felony murder), which lets the narrative move credibly from hospital room to hearing room.

He itemizes eight of nine DSM symptoms—“feelings of sadness and emptiness… recurrent suicidal ideation”—before situating them in the schedule and symbolism of the Senate.

He also names names and dates in the dress code saga, noting Sept. 27, 2023 as the day the Senate unanimously formalized business attire (after an unwritten-code relaxation), an account verified by the official resolution text.

Yes: Unfettered gives enough clinical candor to de-stigmatize treatment—“depression is a disease… eminently treatable”—and enough policy scaffolding to show how justice reform works (or stalls) in practice.

Quotation (book): “When you’re on the Board of Pardons, your biggest fear is that a person you’ve released will get out and commit a violent crime… I was willing to stake my political career on it.”

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

What worked for me.

First, the statistical clarity: Fetterman cites 1,131 Pennsylvanians serving life for felony murder as of 2024; 8,242 life terms overall; a 17× Black-white disparity; 71% of felony-murder lifers are Black—data that aligns with independent reporting.

Second, the moral specificity: he threads the Horton brothers case through his conflict with then–Attorney General Josh Shapiro, showing how politics shadows mercy and why unanimity rules (5–0) are such high bars.

Third, the anti-performance ethic: he skewers the notion that decorum (a suit) equals decency; the SHORTS acronym’s petty dig becomes a lesson in institutional priority inversion.

Where it strained me.

At times Unfettered’s righteous pressure on specific adversaries (and the rawness of personal language) can feel like being pulled into a long corridor of grievance—understandable, but occasionally narrowing the aperture of empathy.

Quotation (book): “The bureaucracy in government is the evil empire… Somebody had to be [a bully].”

6. Reception, criticism, and influence

News coverage since 2023 has reinforced (not softened) the memoir’s two pillars: credible transparency about depression treatment and a willingness to absorb political heat over minor theatrics (hoodies) to focus attention on major policies (commutations). AP, TIME, and The Guardian documented his hospitalization timeline and return, becoming part of the public ledger that Unfettered expands with primary-source detail.

The Senate dress code episode—formalized Sept. 27, 2023—also sparked a lasting debate about symbolism versus substance; even ABC’s recap notes the bipartisan push to reinstate “business attire,” which Unfettered frames as institutional energy misallocated from governing to garments.

In Pennsylvania legal circles, the book’s felony-murder critique intersects with active litigation and commentary on life-without-parole mandates; State Court Report has tracked constitutional challenges, showing how the Unfettered thesis touches real dockets.

7. Comparison with similar works

If you appreciated candid political memoirs that prioritize health and ethics—think Sherrod Brown’s blue-collar dispatches or Katie Porter’s whiteboard populism—Unfettered is rawer and more procedural about clemency.

Where many books offer posture, Fetterman offers vote mechanics (unanimity rules), case histories (Reginald McFadden fallout), and county-level disparities, more reminiscent of an activist’s field manual in passages.

And compared with classic mental-health memoirs, his diction can be scathing toward the self—“Depression is a dark and terrible devil”—which reads more like a firefighter’s log than a therapist’s couch, and may connect especially well with readers allergic to euphemism.

8. A few Pivotal scenes

The blue bridge by the Passage, and the single thought looping—proof that ideation often rides on geography and routine.

The tattoos marking Braddock murders are not performative; they are body-kept ledgers—12-12-07 (Ian Seibert) and 05-24-08 (Radee Berry)—that anchor memory and policy, and the narrative traces how cameras, policing, and community pressure reduced killings for five and a half years. The prose refuses to let those numbers become abstractions. That approach grounds later pardons-board risk calculus.

The McFadden case kneecapped commutations for decades, flipping the standard from simple majority to 5–0 unanimity; six total commutations followed for lifers until a cautious thaw. Knowing that history, you understand why nine lifers recommended for release in one day (Sept. 2019) felt seismic.

Elections still reduce to numbers and patience: 2,751,012 votes and 51.17% in 2022, hard-won even after a halting debate.

The Senate can mobilize in a day to codify suits, but justice reform takes years—Unfettered shows the cost of that asymmetry.

“In Pennsylvania, the mandated sentence for second-degree murder (or felony murder) is life imprisonment without the chance of parole,” Fetterman writes, emphasizing that culpability can hinge on participation in a felony, not on killing. He cites 1,131 felony-murder lifers (2024), 8,242 total lifers, and a 17× Black-white incarceration likelihood on felony murder, with 71% of those cases involving Black prisoners; 87% in Philadelphia, 83% in Allegheny County.

The Felony Murder Reporting Project independently confirms the magnitude and the 17× disparity. When mercy is politicized, he adds, unanimity turns compassion into a near-impossibility, and individual tragedies calcify into policy inertia. That’s the argument in numbers, and it’s hard to shake.

“I had eight” of nine clinical symptoms, he admits, stressing how the mind lies—“depression is a disease… eminently treatable.” His willingness to be treated—documented in Feb. 2023 reports—reframes help-seeking as duty, not detour.

“A suit doesn’t mean anything,” a reader quips, and Unfettered nods: attire can mask sedition as easily as it can mask recovery.

9. Conclusion

If you want an honest, data-literate, post-partisan political memoir that treats mental health, clemency, and governing as one braided story, Unfettered by John Fetterman delivers with receipts, scars, and a measurable theory of change.

General readers will find a survival narrative; policy readers will find a commutations primer; political readers will find a case study in how to withstand the noise long enough to do the work.

Best for readers who want candor and numbers; not for those who require varnish or purely ceremonial civics