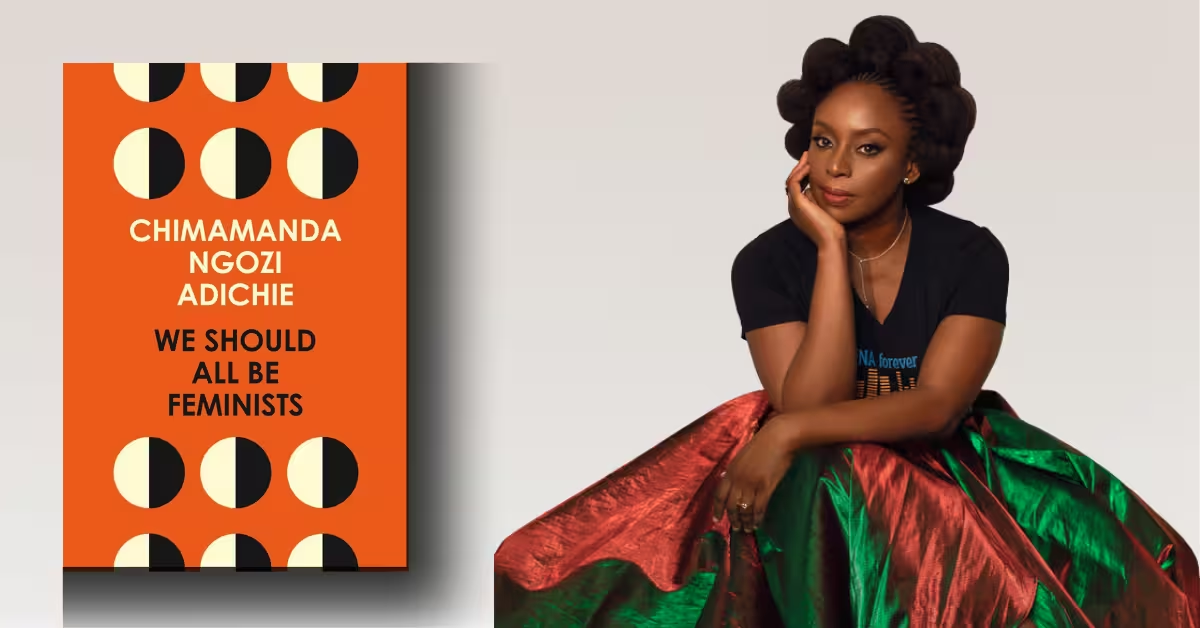

In a world still shaped by invisible rules and inherited expectations, We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie arrives like a clear voice cutting through static—honest, warm, and unafraid to name what so many experience but rarely articulate.

Adapted from her electrifying 2012 TEDxEuston talk and published in 2014, this slim yet resonant manifesto distills the everyday injustices, quiet humiliations, and structural inequalities that define how gender operates across homes, workplaces, and public life.

Adichie draws on vivid personal stories—being denied a childhood class monitor role “because it had to be a boy,” or watching a waiter thank a man for money she herself paid—to expose how culture molds women into smallness and men into rigidity.

With clarity sharpened by lived experience, she insists that the word feminist is neither insult nor ideology but a practical call for “the social, political and economic equality of the sexes.”

What makesWe Should All Be Feminists indispensable is not just its argument but its humanity: it reads less like a lecture and more like a friend explaining the world as it is—and as it could be—if we decided to rewrite its rules.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Gender isn’t a niche problem; it shapes paychecks, politics, safety, and everyday dignity. A feminist is “a person who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes,” and we should all actively build a culture that reflects it.

The World Economic Forum’s 2024 index says the world is 68.5% of the way to parity and, at today’s pace, parity is 134 years away; women hold 31.7% of senior leadership roles and 33% of parliamentary seats globally.

We Should All Be Feminists is best for readers who want a concise, story-rich, globally relevant definition of feminism that welcomes men and women. Not for those seeking an academic history of feminist theory or a comprehensive policy manual—this is a lucid manifesto, not a textbook.

I first met We Should All Be Feminists as a TEDx talk that exploded into a small, orange-covered book in 2014, adapted from Adichie’s 2012 TEDxEuston speech and now one of the most-cited “on-ramps” to contemporary feminism.

It comes from a novelist whose authority is both literary (Purple Hibiscus, Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah) and lived; Adichie writes as a Nigerian woman navigating Lagos and the U.S., and the essay’s power lies in human-sized stories that unmask how “little things” sting.

We Should All Be Feminists‘ central thesis is disarmingly plain: name the gendered problem, refuse euphemisms, and fix culture—because “culture does not make people. People make culture.” (p. 24)

We should all be feminists.

According to Adichie, refusing the word “feminist” dissolves the specific harm facing women into vague “human rights” talk; using the word keeps the real target in view. (pp. 21–22)

And she makes the case with humor, warmth, and clarifying anger—“Anger has a long history of bringing about positive change”—without which comfort usually protects the status quo. (p. 13)

2. Background

Adichie’s essay is literary nonfiction—part memoir vignette, part social commentary, part civic invitation—distilled from a talk that has been watched millions of times and then sampled in pop culture (Beyoncé’s “Flawless” in 2013).

In 2015, Sweden’s Women’s Lobby coordinated the distribution of the book to every 16-year-old student, treating it as civic reading; a public signal that gender literacy is as foundational as math.

That trajectory—from TEDx stage to school classrooms—captures the essay’s genre: a manifesto designed to be read quickly, remembered easily, and applied immediately.

Its stories—from a nine-year-old denied class monitor because “it had to be a boy” to waiters who greet the man and ignore the woman—translate abstraction into pattern recognition. (pp. 9–12)

And the author’s definition is crystalline and quotable: “Feminist: a person who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes.” (p. 24)

3. We Should All Be Feminists Summary

I came to We Should All Be Feminists expecting a short polemic; I left with a compact map for changing how we raise children, speak to each other, and name the problem—because “culture does not make people. People make culture.”

Across this adapted TEDxEuston talk (delivered in 2012 and published as a book in 2014), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie braids memory, definition, and practical prompts: how gender shapes who gets greeted at a restaurant, who is allowed to speak without being labeled “aggressive,” and who is expected to pay the bill.

She opens with the origins of the label—“You’re a feminist,” an old friend once said, not as a compliment—and how a word thick with stereotypes pushed her first toward irony (“Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men… And Who Likes To Wear Lip Gloss”) and then toward clarity.

From there, she tells child-sized and adult-sized stories that reveal the same pattern: institutions and “little things” conspire to shrink girls and to trap boys in brittle versions of masculinity. She remembers being the top scorer for class monitor—then told the role “had to be a boy”—and later, as a grown woman in Lagos, watching a tip she paid be thanked to the man beside her.

At heart, the essay is a practical argument for naming gender as the specific problem to solve—“to choose the vague expression human rights is to deny the specific and particular problem of gender”—and for inviting men in, not as patrons, but as partners who question greetings, bills, and hiring habits in the moment.

Finally, Adichie ends where policy meets intimacy: raise daughters and sons differently, detach masculinity from money, and build a culture that recognizes full female humanity as normal, not radical. “All of us, women and men, must do better.”

Highlights

Adichie anchors We Should All Be Feminists in a real stage and a real year—TEDxEuston, December 2012—where she decided “to start a necessary conversation” about feminism’s stereotypes; the text we read is that talk, published 2014 (Fourth Estate/Vintage).

Her personal gateway to the word feminist is a friendship and a death: Okoloma, the childhood friend who first named her a feminist, died in December 2005 in a plane crash; the memory frames why the label matters and why she refuses to abandon it.

She catalogs the word’s baggage—“you hate men… you don’t wear make-up… you don’t use deodorant”—and parries with playful self-relabeling until she lands on definition instead of deflection. The move is strategic: disarm the noise, then state the thesis.

Definition arrives in two key strokes. First, the dictionary: “a person who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes.” Then her own pragmatic version: “a man or a woman who says, ‘Yes, there’s a problem with gender as it is today and we must fix it.’”

Second, the boundary with human rights: using the generic term, she argues, politely erases women’s specific exclusion—“to choose the vague expression human rights is to deny the specific and particular problem of gender.” Naming keeps the target in view.

The “evidence” is cultural pattern made visible through story. As a girl in Nsukka, she aces the test for class monitor but is disqualified because the role “had to be a boy.” As an adult, she watches a waiter thank the man for her money; later, she notes hotels and clubs that police women’s presence without men. Each small slight maps to a larger lesson: what we repeat becomes “normal.”

She names the emotional economy too: women are trained to be “likeable,” to avoid anger, while men are praised for bluntness; the same behavior read as “tough go-getter” in a man becomes “aggressive” in a woman. The point is not tone but permission.

Then she flips the lens to boys: masculinity as a “hard, small cage” that leaves men with “very fragile egos.” The cost is universal—boys are denied vulnerability; girls are asked to “cater to the fragile egos of males.” Her remedy is developmental: raise both differently.

Marriage becomes a case study in ownership versus partnership: language and expectations assume the woman’s respect is owed upward, while men’s “help” at home is treated as exceptional. She shows how rings, titles, and chores encode hierarchy that love alone cannot erase.

She refuses common conversational detours: appeals to apes, to “poor men have it hard,” or to “bottom power.” We are not apes; class and gender are distinct; “bottom power is not power at all,” merely access to another’s power and thus unstable. The target stays: gender.

Finally, she situates culture in time. Igbo history once marked twins as an “evil omen”—today that is “unimaginable”—which proves culture changes and can be remade to include “the full humanity of women.” She closes by reclaiming the word and the work: “All of us, women and men, must do better.”

Extended summary

Adichie begins with a scene of loss and naming: Okoloma, the friend who first called her a feminist, dies in a 2005 plane crash; his voice survives as the essay’s conscience, the nudge that moves her from discomfort with the word to ownership of it. The point of starting here is ethical—labels are not trivia when they track real harms and real hopes.

She then inventories the myths around feminist—man-hating, humorless, anti-African—and shows how deflection (“Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men…”) doesn’t solve the real problem: a culture that encodes men as default and women as accessory. The pivot to definition—dictionary and her own—reclaims feminism as ordinary fairness.

To demonstrate that gender is structure, not sentiment, she narrates two emblematic experiences. First, childhood: top score, denied class monitor because “it had to be a boy.” Second, adulthood: giving a tip that gets thanked to the man nearby because the waiter assumes money flows from male authority. Repetition, she argues, normalizes bias: what we see “over and over again” becomes what we think is natural.

From these “small” moments, she widens the lens to the workplace and public space. In Lagos hotels and clubs, a woman alone is suspect; at restaurants, the waiter greets the man and “ignores me,” a sting that is intellectually explainable but emotionally bruising. Anger, she insists, is appropriate because “gender as it functions today is a grave injustice”—and anger has “a long history of bringing about positive change.”

She also names how the same behavior is differentially priced: a man’s bluntness is “tough,” a woman’s is “aggressive.” Women learn to chase being “liked” and to swallow resentment rather than speak. The lesson she extracts is not to shame individuals but to notice the rule: we socialize girls to avoid power and boys to ignore likeability; reform must target scripts, not women’s personalities.

Her middle chapters are a manifesto for child-rearing: start again. Raise daughters and sons differently. “Masculinity is a hard, small cage,” she writes, and the cage leaves men with “very fragile egos”; then we ask girls to tiptoe around those egos by shrinking their ambition and pretending not to out-earn men.

The fix is practical: detach masculinity from money, ask “whoever has more should pay,” and teach both children to cook because nourishing yourself is a human skill, not a female gene.

Adichie anticipates common derailments. Evolutionary “ape talk”? We are not apes. “Poor men have it hard”? Class and gender are distinct; poor men still benefit from being men. “Bottom power”? Not real power—merely a precarious route to someone else’s. Each rebuttal keeps the conversation from dissolving into vagueness.

In one of the book’s clearest historical turns, she cites the late Wangari Maathai—“The higher you go, the fewer women there are”—before contrasting a past that rewarded brute strength with a present that rewards intelligence and creativity (“there are no hormones for those attributes”). We’ve evolved; our gender ideas haven’t. That mismatch is the modern policy problem.

Toward the end, she returns to culture with an Igbo example: twins once marked as an evil omen (and killed) are now unimaginable as taboo—proof that culture changes. So, if “the full humanity of women is not our culture,” we must make it our culture. In the final cadence, she reclaims the word feminist—dictionary, then deed—and asks everyone to do better, together.

4. 10 Lessons from We Should All Be Feminists

1. Name the problem clearly—call it feminism, not “human rights.”

Adichie insists that avoiding the word feminist blurs the real issue. Using softer, more “acceptable” labels allows society to sidestep confronting gender inequality directly. Naming the problem is the first step toward solving it.

2. Gender inequality thrives in the “little things” we normalize.

From waiters who address men first to girls taught to be quieter and “likeable,” Adichie shows that structural inequality is built from small daily habits that seem harmless but shape confidence, opportunity, and power.

3. We teach girls to shrink themselves—and boys to overinflate.

Girls grow up hearing they must not be “too ambitious,” “too loud,” or “too assertive,” while boys are raised to believe that vulnerability is weakness. Both scripts stunt human potential and distort relationships.

4. Masculinity is a cage—one that harms men too.

According to Adichie, we raise boys in “a hard, small cage” of masculinity, forbidding emotional expression and tying their worth to dominance and financial success. Feminism frees men by expanding who they are allowed to be.

5. Respectability politics keep women silent.

Women are trained to be “likeable,” to avoid anger, and to sugarcoat truth. This pressure to be agreeable is a tool of control. Adichie argues that women should not have to choose between honesty and social acceptance.

6. Economic independence should not threaten relationships.

Adichie challenges the belief that men must always earn more or pay the bill. Instead, whoever has more should pay—because relationships grounded in hierarchy, not partnership, are doomed to imbalance.

7. “Bottom power” is not real power.

Relying on beauty, charm, or sexuality to gain influence is not empowerment—it’s a fragile, unstable dependence on male approval. Real power is economic, social, and political autonomy.

8. Culture is man-made—and can be remade.

One of We Should All Be Feminists‘ most quoted lines: “Culture does not make people. People make culture.” Harmful traditions weren’t formed by nature; they were built by humans and can be changed by humans.

9. Feminism must include men as allies, not adversaries.

Adichie is clear: the goal is not female superiority but equal partnership. Men need to challenge unfair norms too—by speaking up in restaurants, boardrooms, families, and friendships.

10. To create a just world, we must raise children differently.

The most practical call to action: gender equality begins at home. Teach children—regardless of gender—to cook, care, show emotion, think critically, and value fairness over tradition. A new world requires new socialization.

5. We Should All Be Feminists Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Adichie supports her argument through layered evidence: precise anecdotes, social observations, and a refusal to let language hide power. When she writes “Masculinity is a hard, small cage, and we put boys inside this cage” (p. 15), the metaphor works as both diagnosis and policy brief—raise sons differently.

She integrates data by implication and invites us to check the world outside the page. In 2024, the world had closed 68.5% of the gender gap; full parity is 134 years away; women are 31.7% of senior leaders and 33% of parliamentarians globally—numbers that mirror her insistence that “the higher you go, the fewer women there are.” (pp. 11–12)

The essay’s method is rhetorical judo: instead of blaming girls, it dismantles the expectations that make them shrink—“You can have ambition, but not too much.” (pp. 16, 21) It’s an argument about socialization as destiny unless we intervene.

The purpose is fulfilled.

Her goal is to normalize the identity “feminist,” to claim the word without apology, and to translate feminism into everyday choices—from who pays the bill to who does the dishes to who speaks in meetings. And because the text refuses esoterica, it contributes meaningfully to public literacy on gender for readers who’ll never crack a theory anthology.

6. Reception, Criticism, Influence

The TEDx talk seeded cultural afterlives: Beyoncé’s Flawless” sampled the speech in *2013*, broadcasting Adichie’s definition to global pop audiences and reframing mainstream debates about feminism’s reach.

In 2015, 100,000+ Swedish teens received We Should All Be Feminists via a national initiative—“to work as a stepping stone for a discussion about gender equality”—and outlets from PBS to The Independent covered it as civic pedagogy.

Fashion followed suit: in 2016, Dior sent “We Should All Be Feminists” down a Paris runway, a sign that the phrase had migrated from podium to T-shirt to zeitgeist.

Meanwhile, the world Adichie names remains structurally unequal. In 2024 women held 33% of parliamentary seats and 31.7% of senior leadership roles, with political empowerment on track to parity in 169 years; violence also persists at scale—1 in 3 women globally experience physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetimes.

Critics occasionally fault the essay for brevity or for centering heteronormative scenarios; supporters answer that its clarity is precisely why it scales across classrooms, boardrooms, and living rooms—the point is to start the conversation and widen it, not to end it.

7. Comparison with Similar Works

If you’ve read bell hooks’s Feminism Is for Everybody, Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist, or Mary Beard’s Women & Power, you’ll recognize Adichie’s project: meet readers where they live, then tip the furniture.

hooks does it with pedagogy and intersectionality, Beard with classics and power, Gay with cultural essays; Adichie does it with narrative jolts and a tight manifesto frame. (For reading-list corroboration, see contemporary “best feminist books” lists naming Adichie’s essay as a top primer.)

Unlike Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (economics of creativity) or Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (existential analysis), We Should All Be Feminists is radically brief; its trick is to exchange comprehensiveness for memorability so that people repeat its lines, not just respect them.

And unlike policy-heavy texts, Adichie grounds reform in counter-socialization: raise children differently, invite men in, and treat equality as cultural common sense—not as women’s extracurricular burden. (pp. 15–20)

8. Thematic Close Read

Adichie’s engine is language. She de-weasels generalities—human rights—to name the specific: “to use the vague expression human rights is to deny the specific and particular problem of gender.” (p. 21)

She rejects respectability politics: “I have chosen to no longer be apologetic for my femininity… I want to be respected in all my femaleness.” (p. 21)

She refuses the gendered gag order on anger: “Gender as it functions today is a grave injustice. I am angry. We should all be angry.” (p. 13)

She puts boys in the frame: “Masculinity is a hard, small cage… we put boys inside this cage.” (p. 15) And she names the cost to girls: “We teach girls to shrink themselves, to make themselves smaller.” (p. 16)

Her cultural stance is active: “Culture does not make people. People make culture. If it is true that the full humanity of women is not our culture, then we can and must make it our culture.” (p. 24)

9. Evidence, Numbers, Context

Parity: 68.5% of the global gender gap closed in 2024; at this speed the finish line is in 2158 (approximately 134 years). Women are 42% of the global workforce, 31.7% of senior leaders, and 33% of parliamentarians; economic parity alone could take 152 years.

Safety: The WHO estimates 1 in 3 women experience physical and/or sexual violence; UN agencies reported about 140 women and girls killed each day by a partner or relative in 2023.

Cultural diffusion: Beyoncé’s Flawless (2013/2014) sample carried Adichie’s lines—“We teach girls that they can have ambition, but not too much…”—from TEDx to radio; this pop-cultural echo chamber matters because repetition normalizes ideas.

Civic adoption: Sweden’s nationwide distribution to 11th-graders in 2015 anchored the essay as a classroom conversation starter, backed by discussion guides.

Together, these numbers and moments corroborate what Adichie narrates: the bias is cultural, structural, and fixable only by changing what we teach, reward, and expect.

10. Conclusion

Read We Should All Be Feminists if you want an honest, generous, usable definition of feminism that doesn’t make you choose between data and story.

It is suitable for general readers—teens through executives—precisely because it compresses complexity into language that sticks, and it invites specialists to do the follow-up work of policy, research, and reform.

And it leaves you with lines you can carry into meetings and homes: “People make culture”; “We should all be angry”; “All of us, women and men, must do better.” (pp. 24, 13, 24)

Related