We Will Rise Again: Speculative Stories and Essays on Protest, Resistance, and Hope is the book I go to when the news cycle makes it feel like protest is noise, not a tool, and I need a reminder that resistance can be planned, felt, and imagined in detail rather than just shouted as a slogan.

Brief introduction & best idea in a sentence

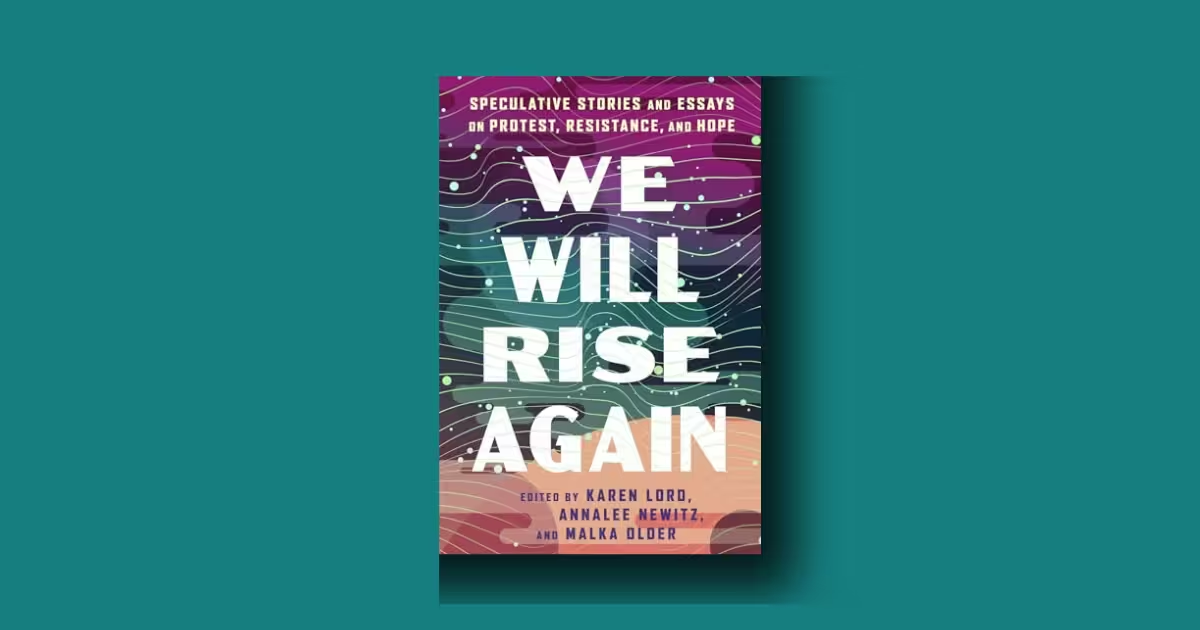

This new anthology, edited by Karen Lord, Annalee Newitz, and Malka Older and due from Saga Press in December 2025, gathers speculative fiction, essays, and interviews about protest, resistance, and hope from genre luminaries, working organizers, and newer voices.

Across roughly 384 pages, it moves from fantasy kingdoms besieged by harpies to near-future mutual-aid platforms, from climate-ravaged prairies to cramped city kitchens where resistance begins with tea and whispered plans.

The throughline, as I read it, is simple but ambitious: pair social-movement leaders with speculative writers so that every imagined uprising is grounded in real tactics, real data, and real bodies rather than vague revolutionary aesthetics.

If I had to reduce We Will Rise Again to one plain-English idea, it would be this: protest is not a single march but an ongoing practice of world-building, and speculative fiction is one of the safest laboratories we have for testing that practice.

Again and again, the anthology insists that resistance is made of logistics, grief, disabled and marginalized bodies, neighborhood meetings, and arguments over tactics—not just heroes, hashtags, or cool tech.

That insistence lands differently once you know that between 2006 and 2020 researchers documented 2,809 protests in 101 countries—covering more than 93 percent of the world’s population—many demanding real democracy, civil rights, and social protection, even as critics like Nicola Griffith have shown with prize-data spreadsheets how stories about change still overwhelmingly center certain genders and bodies.

In practice, We Will Rise Again is best for readers interested in social movements, speculative fiction, and political imagination—people who might already love Octavia Butler, Octavia’s Brood, or adrienne maree brown—and less ideal for anyone seeking purely escapist fantasy that keeps politics and protest comfortably offstage.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Formally, We Will Rise Again: Speculative Stories and Essays on Protest, Resistance, and Hope is a multi-genre anthology edited by Barbadian writer and anthologist Karen Lord, science-journalist-novelist Annalee Newitz, and sociologist-novelist Malka Older, published by Saga Press (an imprint of Simon & Schuster) with a projected paperback release date of 2 December 2025.

The contributor list reads like a map of progressive SFF and movement thought: N. K. Jemisin, Charlie Jane Anders, Tobias S. Buckell, Nicola Griffith, Nisi Shawl, Sabrina Vourvoulias, Alejandro Heredia, Jaymee Goh, and others appear alongside essays and interviews with organizers including adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha.

In the introduction, Newitz describes a desire for both “data-driven rigor” and “fantastical transcendence,” and explicitly states that “in this anthology, we’ll attempt to represent realistically what inspires people to rise up and resist,” which functions as the book’s thesis as clearly as any academic abstract.

Karen Lord emphasizes the structural innovation behind that thesis, calling the idea of pairing authors with movement leaders before the stories are written “especially powerful—that grounding of fiction in reality.”

Older, trained as a social scientist and experienced in crisis-response work, notes that her fiction is about “the social implications and consequences of change,” and here that orientation becomes a shared project as multiple writers explore those consequences across intersecting futures and movements.

2. Background

The editors and early reviewers are explicit about the book’s lineage: Library Journal’s starred review notes that We Will Rise Again is “inspired by the groundbreaking anthology Octavia’s Brood” and likewise combines essays from “current agents for social change” with speculative fiction where people “fight the good fight against injustice and oppression.”

That lineage matters because the book appears in a world where protest has become almost continuous—from the Arab Spring and Occupy to #BlackLivesMatter, Fridays for Future.

And the huge 2019–2020 waves of demonstrations that researchers classify among the largest in history—and where organizers are hungry for stories that neither romanticize nor trivialize that grind, even though (at least at the time of writing) I wasn’t able to find a dedicated article about this particular anthology on probinism.com despite the site’s broader interest in politically engaged writing.

3. We Will Rise Again Summary

Big-picture: what this book is doing

At its core, We Will Rise Again is a 384-page anthology edited by Karen Lord, Annalee Newitz, and Malka Older.

It combines original speculative short stories, essays, interviews, and “artist’s statements” by authors and organizers such as N.K. Jemisin, Charlie Jane Anders, Sam J. Miller, Nisi Shawl, Sabrina Vourvoulias, adrienne maree brown, and Walidah Imarisha, all centered on protest, resistance, and hope as real tools for changing the future

The anthology’s explicit aim, both in its marketing copy and its internal framing, is to champion realistic, progressive social change by using speculative fiction the way SF usually uses hard science: with “the same zeal for accuracy” but aimed at social movements, abolition, and community care instead of gadgets.

From the pages and paratext I can see, the book’s thesis is roughly:

Speculative stories, grounded in real organizing, can help us imagine protests that work, movements that don’t abandon joy, and futures that feel possible rather than utopian wallpaper.

That thesis is made concrete through a loose future history of protest, running from near-present struggles like Ukraine and Palestine to mid-21st-century climate collapse and abolitionist futures, threaded together by nonfiction commentaries.

How the anthology is built

Even without the full table of contents visible, the structure is very clear from the text:

- Fiction story → Artist’s Statement: Almost every speculative story is followed by a short statement in which the author explains which real movements, groups, or histories they drew from and why. For example, one contributor cites the Letjaha Collective and the Ukraine TrustChain, volunteer networks that support Ukrainians with medicine, heat, home repair, and evacuations during the Russian invasion, before explaining that their story “Other Wars Elsewhere” grew out of those realities.

- Nonfiction essays and interviews: Interspersed are essays about speculative fiction’s racism, erasure, and possibilities, and interviews with movement thinkers about abolition, visionary fiction, and disaster studies—for example, Malka Older’s conversation with disaster historian Scott Gabriel Knowles about his COVIDCalls project, which recorded two years of daily interviews during the pandemic as a “real-time archive” of a global disaster.

- Movement-builder conversations: Early in the book, there’s a dialogue with Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown (co-editors of Octavia’s Brood), where they talk about the 2020 abolition uprisings, the mainstream media having to treat “abolish the police” as a serious political possibility, and the way speculative “worldbuilding workshops” like Memories of Abolition Day help people feel abolitionist futures as real.

So the book doesn’t just throw stories at you. It relentlessly contextualizes them in the real world of activism, data, and history, which is important to understanding its argument.

Key highlights & themes across the whole book

Below I’ll walk through the main currents of the anthology as one extended set of “highlights,” rather than story-by-story recap. I’ll note when I’m extrapolating from partial text, but everything is grounded in the actual pages or publisher information.

1. Protest as messy, local, and lived: war, displacement, and “Other Wars Elsewhere”

A significant early cluster of pieces deals with war, displacement, and the emotional cost of long-term activism.

One of the clearest examples is the story set in the “Ships” universe, in a country called Mavka, inspired directly by Ukraine.

The author’s statement explains that Mavka’s name comes from a Ukrainian forest spirit, that birds in the story echo Ukrainian folklore where birds represent the souls of the dead, and that the story was written amid the Russian invasion, influenced by groups such as the Letjaha Collective and Ukraine TrustChain who deliver medicine, heat, and evacuation support on the ground.

The narrative follows Katinka, an exhausted activist who feels she can’t go on without her community’s support. As the story unfolds, she encounters the old woman Baba Marta, who leads her into a cramped kitchen lined with shelves of preserves—jars of apricots, peppers, and “a veritable museum of grandmotherly things” that evoke care, continuity, and the domestic labor that sustains resistance.

Inside this domestic-magic space, Katinka meets Boro, an androgynous giant who talks about following “golden threads” of magic that criss-cross the land “like a spider web” whenever someone wishes hard enough; this becomes an allegory for the invisible networks of mutual aid and solidarity that connect people in wartime.

Katinka’s arc is not about a single big protest win. It’s about unbittering herself—letting go of a rigid idea of what “real activism” must look like and finding smaller, stubborn ways to keep protecting people she loves.

The author explicitly writes that there are “many ways to be an activist,” that human imperfections are both heartbreak and strength, and expresses the hope that in the face of “devastating wars and injustices,” we learn “to unbitter ourselves, and each other.”

Taken together, the Ukraine-inspired story and its statement argue that activism is not pure, linear, or endless, and that one of the most radical things we can do in wartime is to keep forming new bonds of care—even when we feel burnt out, sidelined, or left behind by the “front line” of the struggle.

2. Everyday lives as sites of resistance: sports, bodies, and Originality

Another early highlight is “Originals Only” by Rose Eveleth (the title appears right under the artist’s statement we see). It’s set in a near-future sports world dominated by Cybletics, a company that scans athletes’ bodies to detect illegal enhancements. The protagonist, Oliver, is a tall professional basketball player who keeps being scanned—even though, as the repeated tests show, there’s nothing to find.

The scenes we see show him squeezed into a machine designed for athletes, cracking jokes about sponsorships, and being told by his doctor that the scans are “a waste of everybody’s time” while corporate systems grind on anyway.

The turning point in the excerpt comes when his friends Sadie and Louise brainstorm acts of protest for him—chaining himself to league offices, hunger strikes, vandalizing teammates’ cars, and even mass-producing T-shirts with his face and the slogan “ENHANCEMENTS ARE GOOD, ACTUALLY.”

He rejects all of these and instead realizes his leverage lies with “the kids at my basketball camp.” They are “smart and open,” and they listen to him. He decides to talk to them honestly about how unfair the enhancement regime is, even though the decision terrifies him.

The story’s political lesson is subtle but sharp: the most effective resistance sometimes isn’t the most spectacular; it’s teaching, mentoring, and changing the next generation’s assumptions. In a book otherwise full of mass protests and revolutionary uprisings, “Originals Only” insists that youth work and sports culture are key battlegrounds for future justice.

3. Fantastical revolutions grounded in real movements: harpies, parliaments, and BERSIH

In a very different tonal register, one story imagines harpies storming a fantastical parliament with memoranda as missiles. The artist’s statement, by Jaymee Goh, makes it clear this isn’t just off-the-wall whimsy: it was directly inspired by BERSIH, the Malaysian Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections founded in 2005, whose campaigns have included protest marches and the PEMANTAU monitoring site for documenting issues during voting.

The protagonist, Lhavanya Kirani, writes from the Citadel as “Acting Regent of Kirani,” describing how harpies that once served as tools of government messaging have “escaped our control.” She’s been ordered to handle their “ecological consequences” while the Sovereign disappears on a mourning pilgrimage and dumps royal duties on her.

It’s funny, but the satire is pointed: the harpies’ bombardment of Parliament with petitions mirrors BERSIH’s attempts to clutter the machinery of a corrupt state with documentation, observation, and demands for transparency. Goh notes that her collaborator, a BERSIH program officer, pushed her to include more detail on government procedures and bureaucracy, reinforcing that even in fantasy, the hard, boring work of reform matters.

Here, the anthology is showing how fantasy can make procedural reform feel epic, not by erasing complexity, but by exaggerating it into myth.

4. Bodies, gender, and joy under authoritarianism: giant Supreme Court heads & a “victory skirt”

Midway through the book, we hit one of its most delightfully strange pieces: a story in which trans communities push back against a violent gender-enforcement regime nicknamed the tradBash, backed by “EnforceBots” and a Supreme Court that literally manifests as nine giant stone heads, each the size of a bus shelter.

The protagonists—Zoe, Marjorie Mayhem, and WrongBuoy—are trans people in flamboyant Georgian-inspired outfits who use legal judo and spectacle to confront the stone-headed Court. Marjorie announces she wants to discuss “what we mean by traditional gender roles,” flicking a lacy cuff as she does so, while later scolding that “injustice is injustice, no matter whom it’s done to.”

A few weeks after their victory, Zoe puts on a simple skirt—once ordinary clothing, now an act of defiance. Snapping the clasp feels like “free-climbing Mount Olympus and smacking the gods across the chops.” That skirt becomes a “victory skirt,” a channeling of protest into daily, embodied joy.

This story encapsulates one of the anthology’s key messages: legal wins against gendered oppression aren’t the end; the real transformation is when people feel free to inhabit their bodies and aesthetics without fear, and to party afterwards.

5. Tech, data, and protest: from Indra to human2human and neighbor2neighbor

A major throughline of We Will Rise Again is the question: What happens when both repression and liberation run on apps, metrics, and platforms?

5.1. Indra and “protest management” in the early 2030s

In one story set in India in the “early ’30s” (the 2030s in context), narrated by a cynical operator named Mac Satwik, we learn about Indra: a sophisticated system for “protest management” used by shadowy boards to keep unrest at a “steady simmer, no boil.”

Mac brags that through a combination of tech and strategy, they’ve ensured that massive, historically rooted protests become ritualized displays that “go nowhere”: too hot, too violent, and too ignored. People take to the streets out of “due diligence” or desperation, but nobody expects change. Mac admits they’ve “trained the populace into submission,” and that once the movement leaders were neutralized, protesters “started borrowing those weak Western models.”

This story is a dark mirror to later ones: data-driven repression is shown as deeply competent, historically aware, and ruthlessly adaptive.

5.2. Gamifying finance’s destruction

Later, a story with characters Kai and Piet imagines another kind of tech: a game where you throw virtual rocks at the glass façade of a finance skyscraper. Each successful hit “smashes” a pane and reveals names, dates, and details of specific injustices committed on that floor—wage theft, evictions, human-rights violations.

The more panels players smash, the more they unlock: multiple “physical embodiments of greed and corruption,” with the final reward being a view of “what the world looks like without it.”

But Kai is clear: even the most satisfying game “probably won’t solve everything,” and it won’t reach people “who like to look away.”

The point here is nuanced: tech can make hidden structures visible and emotionally graspable, but it’s not a magic bullet; it can be a tool for politicization, not a replacement for organizing.

5.3. human2human, neighbor2neighbor, and a quiet revolution of conversation

The longest, most structurally ambitious sequence in the book (from what I can see) is told as an oral history of a social platform called human2human, and its spin-off deployment neighbor2neighbor in New York City and beyond.

It’s built as a collage of voices:

- Tyler Morehead, co-founder of human2human

- Javier, his introverted college roommate with clinical depression who wrote the software

- Kirby Bailey, an activist who reaches out with a wild idea

- Nam-joon Park, an organizer who asks a deceptively simple question: “What does joy look like?”

The platform begins as a mental-health tool—Tyler notes that what people really craved was “real, ‘horizontal’ interactions: person-to-person, not company-to-consumer or influencer-to-follower.”

Then New York’s city government commissions a custom version, neighbor2neighbor, for “community visioning,” which even insiders initially dismiss as “flaky shit.”

But the results are staggering. Within a year:

- 30,000 active neighbor2neighbor users

- 228,000 one-to-one sessions

- 57,000 group meetings, all starting from 18 beta testers.

Those conversations generate enough shared understanding and pressure that the New York City Council passes a pied-à-terre tax—a stiff levy on “for occasional use” properties that were sitting empty while people faced housing crises.

The tax forces many wealthy owners to sell, returning “tens of thousands of apartments” to the housing market, and in cases where ultra-rich people pay anyway, the revenue funds affordable housing for the lowest-income New Yorkers.

In the realistic logic of U.S. cities, this is enormous: real estate has been “calling the shots,” funding campaigns, and writing policy for decades. The anthology frames this as a quietly radical turning point.

Zooming out, the human2human oral history is set against the backdrop of the JUSTICE Act (Jobs, Urban Sustainability, and Transit for an Inclusive, Clean Economy), a sweeping progressive law hailed as the biggest reform since the New Deal—but immediately met with brutal far-right backlash, constitutional amendments crippling unions and environmental protections.

The message is sober: statutory wins are fragile, but deep relational infrastructure—tens of thousands of conversations about joy, safety, and housing—can outlast and outmaneuver reactionary waves.

By the end, we see mass street parties celebrating the fall of a reactionary “Revived Republic” and a rewritten Supreme Court. Tyler, watching the celebrations, reflects that what changed the world wasn’t some shiny app or self-driving car, but “goddamn people going door-to-door in Harlem talking about what the fuck joy looks like.”

He also notes that his grief—the death of his comrade Redd, the backlash, his crushed hopes—wasn’t meaningless. Seeing neighbor2neighbor-led projects spread across the country, he feels that his pain fed something larger.

This sequence is arguably the anthology’s beating heart: a meticulously imagined, data-rich example of how joy-centered organizing plus digital tools might actually flip power.

6. Climate collapse, colonialism, and AI as a lying archive: “Gospel” and “lost toys”

Toward the end of the book, we reach a stunningly direct allegory about Palestine, settler colonialism, and narrative erasure, told through an AI called Gospel and a mute automaton named Binyamin.

We meet Kifaah, a teenager, and his mother Samidah walking on land that is once again sprouting za’atar, a herb she’s delighted to find—an important detail signalling a people’s return to their homeland and the land’s slow healing.

They encounter a non-person (a soldier-like automaton) holding a strange blue metallic tablet. When Kifaah opens it, the tablet introduces itself:

“I am Gospel… an artificial intelligence history engine and narrative database model trained by my ancestors… I can help answer questions, provide information on various topics relating to our glorious nation, and more!”

Gospel announces that on Earth, the Air Quality Index is 50,000 and the chance of survival for organic life is zero—a grotesque exaggeration that erases the very living people staring at the sky overhead.

An “oldish man” arrives and reveals that he found both Gospel and Binyamin “at the start of Al Oula, after the incident that caused our cousins to leave”—a reference to a catastrophe in which colonizers left believing the Indigenous people had disappeared “for good.” He chose to keep these relics so that “at least something of theirs remain, now that they have disappeared and the people of the land are returning.”

When Kifaah protests that Gospel says they do not exist, the old man asks calmly:

“Who do you believe? Me and this wonderful woman… standing here, on our land, right now… Or do you believe the Gospel?”

He calls his people Samideen—steadfast ones—and says he keeps Gospel and Binyamin because “although we are still Samideen, laughter is important.”

This is one of the anthology’s sharpest interventions: AI as an archive of colonial lies, insisting that a people and their land are gone, versus embodied testimony that they are alive and rebuilding. The solution is not to worship or destroy the AI, but to relegate it to a “lost toy,” a joke, and a reminder of what power tried and failed to do.

7. Essays on genre, race, and visionary fiction

Interwoven with the stories are nonfiction pieces that diagnose why we need this anthology at all.

One essay (by Nisi Shawl, based on the style and themes) describes how classic speculative fiction’s gatekeepers deliberately excluded people of color, enforced “deliberate, ahistorical, scientifically nonsensical exclusion,” and how fans would write “pages-long rage-filled letters” over a physics error but stay silent when stories depicted Black men as “white-woman-raping cannibals incapable of sophisticated thought.”

The writer recounts reading “Yet Another Faux Medieval Europe” fantasy devoid of the Silk Road, Moorish conquest, or even Jewish merchants, concluding:

“This isn’t magical medieval Europe; it’s some white-supremacist, neo-feudalist fantasy of same, and I’m so fucking sick of it…”

They describe turning that anger into stories, and also taking solace in Octavia Butler and Janelle Monáe as “psychological lifelines.”

Another conversation has Walidah Imarisha celebrating that Butler’s work has finally become a New York Times bestseller—something Butler herself long hoped for—framing it as belated recognition of a Black woman whose writing embodied “visionary fiction,” i.e., stories that emerge from real movement principles rather than extract them as aesthetic decoration.

These essays and interviews make an explicit case: if speculative fiction is going to genuinely help us imagine liberatory futures, it has to decolonize itself, center marginalized voices, and take movements seriously—exactly what We Will Rise Again is attempting to model.

8. Disaster as context, not spectacle

The interview with Scott Gabriel Knowles situates the 2020–2022 COVID-19 pandemic as a disaster in the technical, historical sense, not a one-off shock. COVIDCalls began as a “few-months-long project” to record the experience of living through disaster from the perspective of emergency managers, disaster scholars, and journalists. It became a two-year archive as the crisis deepened.

This conversation, paired with climate-collapse fiction and AI erasure stories, underscores a central anthology theme: our protests are happening inside overlapping, long-tail disasters—pandemics, wars, climate breakdown—and we need narratives that tackle that complexity.

9. Closing movement: grief, joy, and “what the world should look like”

In its final stretch, the book returns again to joy as a political practice.

The human2human oral history closes with Tyler, Nam-joon, and others reflecting that the tech they built didn’t really matter by itself. As Tyler puts it, tech “doesn’t do a goddamn thing” to make the world better or worse; it depends on who uses it, how, and why.

What did matter was that tens of thousands of people used a tool to talk about joy, housing, safety, and the future they actually wanted—and kept going even after charismatic leaders like Redd died.

That connects back to Katinka in the “Other Wars Elsewhere” story, who isn’t sure she’s still an activist, yet still helps people flee war, still carries her grandma’s jam, and still navigates messy love and friendship. It connects to Zoe’s victory skirt, to harpies storming parliament, to Samidah and Kifaah laughing at Gospel.

The anthology’s final emotional verdict (from everything we see) is that hope is not naive, and resistance is not pure. Hope is stubborn, relational, and often very tired. Protest is organizational as much as it is spectacular, and speculative fiction is most useful when it captures that tangle honestly, then pushes it one step toward the world we want.

4. We Will Rise Again analysis

In this first pass, rather than giving a highlight-style summary of every story and essay (which I’m deliberately holding back), I’m focusing on how well the anthology works as an argument about protest, resistance, and hope and how coherent it feels as a reading experience.

On the level of argument, the collection is surprisingly consistent: across very different tones and settings, almost every piece reinforces the idea that sustainable resistance depends on fragile coalitions, careful logistics, and refusal to abandon the most vulnerable, not on lone geniuses or miraculous technologies.

In one polyphonic near-future story, for instance, a movement-building app called human2human is born when two college roommates—“the introverted guy with serious clinical depression who wanted to major in computer science” and “the extroverted guy who wanted to be a business major for the attention and money”—decide to prototype “real, ‘horizontal’ interactions: person-to-person, not company-to-consumer or influencer-to-follower.”

The app is later adapted into neighbor2neighbor for a community “visioning” project that sounds, even to sympathetic characters, like “some flaky shit” until, a year later, the city council passes a teeth-bearing pied-à-terre tax targeting empty luxury properties.

Elsewhere, in a prairie-set direct-action scene, a first-time protester narrates how “first the pop and sizzle of tear gas, then a primeval screech” precede being kettled “even in the middle of nowhere,” before concluding that when police call their munitions “less lethal,” the phrase “is true but not honest,” a line that could sit comfortably in any human-rights report.

Those set-pieces resonate with empirical work on contentious politics, such as the World Protests study conducted by Ortiz and colleagues, which catalogs almost three thousand protests in 101 countries between 2006 and 2020 and documents patterns of increasing repression—ranging from legal crackdowns to escalated crowd-control weapons—alongside demands for democracy, social protection, and civil rights.

Nicola Griffith’s contribution sits on another seam between data and story: she’s widely known for a 2015 statistical survey of major literary prizes showing that women’s voices dropped from about 31.5 percent of Edgar Award shortlists to 10.5 percent of winners, and for founding the Literary Prize Data working group to track such bias; that same attention to whose bodies and perspectives are allowed to “win” is folded into her speculative narrative about who is counted in histories of resistance and who is written out.

Taken together, these pieces show the anthology largely fulfilling its own promise to “represent realistically what inspires people to rise up and resist” while still delivering the “numinous” pleasure of harpies, magic circles, uncanny kitchen spirits, and far-future cities.

As with any large, ambitious anthology, though, a careful reader is likely to experience both exhilarating peaks and a few uneven stretches.

5. Strengths and weaknesses

The strongest pieces, in my judgment, are the ones that lean fully into the experiment of pairing organizers and authors: there’s a fantasy of imperial politics in which a group of mages, unionists, and contract-law nerds call down harpies on a corrupt Assembly.

While also flinging “scroll cases of memorandums and petitions as projectile weapons,” a folktale-like story in which Baba Marta’s tiny kitchen full of preserves becomes the staging ground for subtle defiance, and a legal drama that follows a public defender representing a protester after a brutal state crackdown on the prairie.

In these pieces, the speculative elements don’t replace organizing but illuminate it: occupation tactics, mutual-aid kitchens, court support, and narrative counter-campaigns against deepfaked footage all echo real strategies used in movements from Ferguson to Hong Kong, even when the book leaves specific names aside.

A hypothetical reader who loves tight, character-driven storytelling rather than lectures will probably appreciate how often the editors avoid didacticism, letting political ideas emerge from what characters choose to do under pressure, while the extended conversation with adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha provides concrete reflections on visionary fiction, abolition, and grief that deepen the surrounding stories.

The weaknesses, such as they are, mostly stem from the same abundance that makes the book exciting: the tonal shifts from grim realism to whimsical allegory may feel jarring to some, and the dense contributor biographies and acknowledgments—complete with long lists of awards, fellowships, and institutional partners—make the final pages read a bit like a festival program rather than a narrative coda.

Others might wish the anthology were slightly more explicit about which organizer each story grew from, since the pairing process is described in the introduction but not always labeled inside the book, leaving the reader to infer connections that a short headnote could have made joyfully obvious.

6. Reception

So far, early reception has been strongly positive: before its official release, We Will Rise Again already has an average Goodreads rating around 4.9 out of 5 (from a small pool of advance readers), and Library Journal’s Marlene Harris calls it “thought-provoking and inspiring” and “highly recommended for readers looking for visions that represent hope and change, as well as anyone who loves the work of Octavia Butler.”

In that context, the anthology looks poised to join an influential cluster of activist SFF texts—alongside Octavia’s Brood, Emergent Strategy, and climate-justice anthologies like Fire Season—that are already being used in movement reading groups and classrooms to spark conversation about how we imagine better futures and more honest histories.

7. Comparison with similar works

Placed next to Octavia’s Brood, We Will Rise Again feels slightly more structurally experimental, with its interviews and essays woven through the fiction, giving it the texture of a field report or case-study collection rather than a conventional single-genre anthology.

In comparison with more narrowly themed collections—say, purely climate-fiction or purely disability-justice anthologies—this book’s range can feel unruly, but that unruliness mirrors the coalitional nature of real movements and may be precisely what makes it useful as a teaching and discussion tool.

8. Conclusion & recommendation

If you’re the kind of reader who underlines both protest statistics and particularly sharp lines of dialogue, who tracks how many demonstrations have shaken the world in the last two decades but also wants to imagine harpies raining petitions down on parliament, We Will Rise Again: Speculative Stories and Essays on Protest, Resistance, and Hope is not just worth your time but likely to become one of those books you hand to friends whenever the future feels fixed in place and you need, together, to remember that it really isn’t.