If you feel stuck between ambition and circumstance, Wings of Fire shows how a boy from Rameswaram turned scarcity into India’s space-and-missile renaissance—without losing humility or hope. It solves the problem of “How do I start from very little and still build something vast?”

Wings of Fire argues that disciplined learning, spiritual steadiness, and team-centered leadership can convert a modest life into national-scale impact—what Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam himself calls giving “wings” to the “divine fire” within us.

The memoir documents the Indian space program’s evolution from hand-lifted sounding rockets to indigenous launch vehicles and ballistic missiles; it records concrete projects (Nike–Apache at Thumba; Rohini; SLV-3; IGMDP) and managerial choices under leaders like Sarabhai and Dhawan.

Externally, historical summaries corroborate the publication details and the IGMDP’s concurrent development of Prithvi, Agni, Akash, Trishul and Nag under Kalam’s stewardship.

Best for readers who want an engineering-grounded, spiritually reflective blueprint for self-education, leadership, and nation-building; not for those seeking gossip, cynicism, or a purely literary memoir without technical context.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

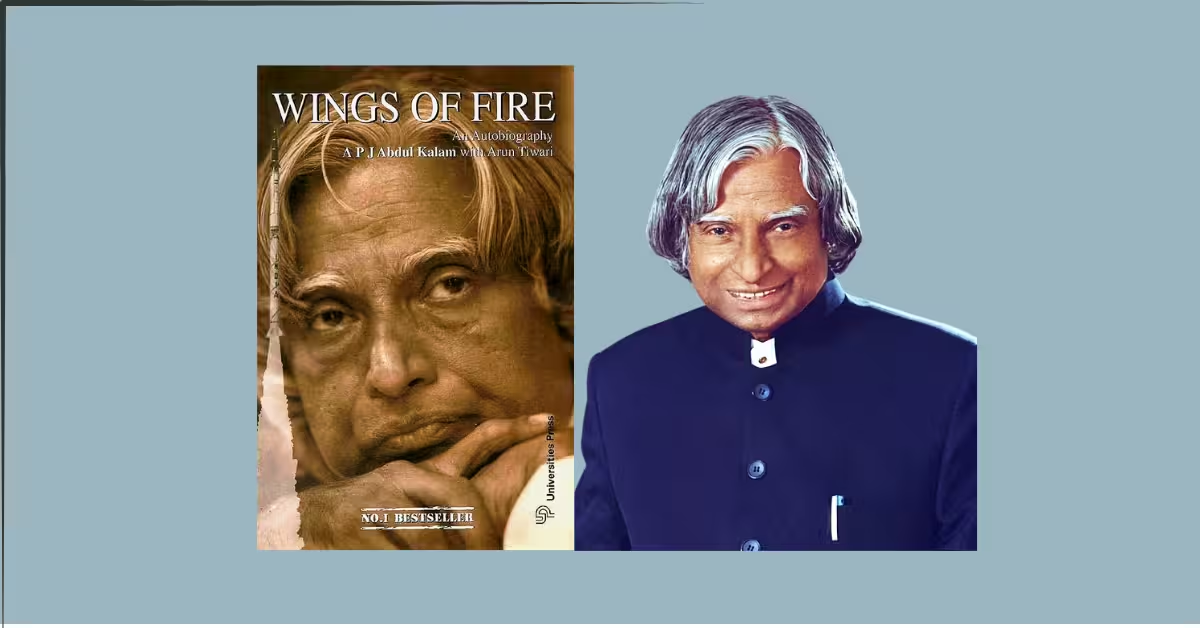

Wings of Fire: An Autobiography is co-authored by A. P. J. Abdul Kalam (1931–2015) and Arun Tiwari; first published by Universities Press (Hyderabad) in 1999, paperback ISBN 9788173711466. Universities Press lists 1999, paperback, and a detailed table of contents; library records echo the 1999 Hyderabad publication.

The book is an autobiography that doubles as an institutional history of India’s rocket and missile programs, spanning childhood in Rameswaram to leadership at ISRO and DRDO. It interleaves prayerful reflection with precise engineering milestones—e.g., Nike–Apache at Thumba (1963), Rohini sounding rockets, SLV-3, and later IGMDP.

Kalam’s thesis is that we are “all born with a divine fire” that must be given “wings” through work, learning, and service—an inclusive, spiritual-technical credo repeated at the book’s threshold.

2. Background

I came to Wings of Fire as a reader who oscillates between policy, technology, and the humanities; the book lands at that intersection. It emerged during the late-1990s moment when India’s space successes and guided-missile program were becoming national identity markers, with Kalam soon to be called the “People’s President” (2002–2007), as global profiles and obituaries later reinforced.

The memoir should be read against the historical arc: from colonial-era setbacks (Tipu Sultan’s rocket legacy) to modern reverse engineering and indigenous capability—an arc the book narrates vividly, including the Wallops painting of Tipu’s rockets that jolts the author into historical continuity.

3.Wings of Fire Summary

Origin—Rameswaram

Kalam, “a short boy with rather undistinguished looks,” grows up on Mosque Street, Rameswaram, in a mixed Hindu–Muslim neighborhood, secure “materially and emotionally,” with a father of “great innate wisdom” and a mother whose generosity fed “far more outsiders” than family.

Prayer and pluralism are formative. Even without understanding the Arabic words, he knows the prayers “reached God,” and the temple’s high priest Pakshi Lakshmana Sastry is his father’s close friend—images that prefigure Kalam’s lifelong blending of faith and science. His father’s definition of prayer—“communion of the spirit … you transcend your body and become a part of the cosmos”—becomes a cognitive habit for ideation.

Teachers and hunger for learning

From Schwartz High School to the Madras Institute of Technology, teachers channel his “intellectual hunger” (Prof. Sponder, Pandalai, Narasingha Rao). This teacher-centric ethos—“feed their students’ intellectual hunger by sheer brilliance and untiring zeal”—later informs his own leadership style at ISRO and DRDO.

NASA apprenticeship and the Nike–Apache launch

A stint at Langley and Goddard immerses Kalam in U.S. R&D. A painting at Wallops shows Tipu Sultan’s rocket troops—South Asian faces firing rockets—reminding him that Indian rocketry isn’t a copy; it is a revival.

Back in India, the 21 November 1963 Nike–Apache launch is executed with barebones equipment, a leaking crane, and sheer human strength—Kalam handles integration and safety while colleagues manage radar and ground support.

Leadership by trust—Sarabhai and Dhawan

Vikram Sarabhai’s genius, says Kalam, was trusting young, inexperienced teams and resolving uncertainty through experimentation. Later, when a senior scientist questions Kalam’s own contribution, Sarabhai intervenes—“the project leader [is] an integrator of people”—a line that crystallizes Kalam’s team philosophy.

Rohini sounding rockets → SLV-3

The book distinguishes sounding rockets, launch vehicles, and missiles with clarity; Rohini grows from a 32-kg motor lifting 7 kg to two-stage configurations lifting ~100 kg to >350 km, seeding indigenous propellant and guidance capability and leading to VSSC and SLV-3.

Setbacks and grit

There are burns, failures, and grief. In 1979 an RFNA tank bursts, severely injuring six; Kalam keeps vigil and records a colleague’s first words—regret for schedule slippage even in pain—a portrait of team ethic. He frames the period as “single-minded devotion,” rejecting the label workaholic: “If I do that which I desire … such work can never be an aberration.”

RATO to SLV-3, then IGMDP

The RATO system (jet-assisted take-off) shortens a Sukhoi-16’s run from 2 km to 1.2 km, saving ~₹4 crore in foreign exchange; indigenization reduces unit cost from ₹33,000 (imported) to ~₹17,000. Kalam recounts budgets (<₹25 lakh) and management structures that made it possible.

The missile decade

By the early 1980s, DRDL channels R-&-D from “reverse-engineering” to original design. The IGMDP emerges, backed by Defence Minister R. Venkataraman’s insistence on simultaneous development and his exhortation—“What you imagine is what will transpire”—and builds Prithvi, Agni, Akash, Trishul, Nag, with the Interim Test Range at Chandipur/Balasore.

The tone of service

The book’s final movement is devotional: “All these rockets and missiles are His work through a small person called Kalam … We are all born with a divine fire… give wings to this fire.” This is not ornament; it’s his operating system—humility tethered to scale.

Highlighted lessons across the narrative

- Purpose amplifies talent. “We are all born with a divine fire … give wings to this fire.”

- Leadership integrates people. “A project leader [is] an integrator of people.”

- Trust breeds institutions. “Leadership by trust” at INCOSPAR empowered the young to build TERLS and beyond.

- Adversity → introspection → progress. “Adversity always presents opportunities for introspection.”

- Humility ≠ softness. Beware “contemptuous pride” in organizations; draw the “fine line” between firmness and bullying.

- From history to strategy. Tipu’s rockets symbolize a continuity reclaimed by modern Indian rocketry.

- Infrastructure is sacred. When siting test ranges, “design … without disturbing” Chandipur’s bird sanctuary—technology with stewardship.

4. Wings of Fire Quotations

Here are 20 inspiring, quotable lines/passages from Wings of Fire (APJ Abdul Kalam with Arun Tiwari). I’ve kept each excerpt exactly as in the book and cited the precise location so you can verify or quote with confidence.

- “We are all born with a divine fire in us. Our efforts should be to give wings to this fire and fill the world with the glow of its goodness.”

- “I have always seen a project leader as an integrator of people and that is precisely what Kalam is.” — Vikram Sarabhai (during an SLV-3 review)

- “What makes life in Indian organizations difficult is the widespread prevalence of this very contemptuous pride… The line between firmness and harshness, between strong leadership and bullying, between discipline and vindictiveness is very fine, but it has to be drawn.”

- “Problems can be the cutting edge that actually distinguish between success and failure. They draw out innate courage and wisdom.”

- “As we were fast approaching the launch time… any repairs to the crane had to be ruled out. Fortunately, the leak was not large and we managed to lift the rocket manually, using our collective muscle power and finally placing it on the launcher.” (on India’s first Nike–Apache launch, 21 Nov 1963)

- “Prayer made possible a communion of the spirit between people. ‘When you pray,’ he said, ‘you transcend your body and become a part of the cosmos, which knows no division of wealth, age, caste, or creed.’” (Kalam quoting his father)

- “In his own time, in his own place, in what he really is, and in the stage he has reached—good or bad—every human being is a specific element within the whole of the manifest divine Being… Adversity always presents opportunities for introspection.”

- “I take responsibility for the SLV-3 failure. … Then Prof. Dhawan got up and said, ‘I am going to put Kalam in orbit!’”

- “The pursuit of science is a combination of great elation and great despair.”

- “Big scientific projects are like mountains, which should be climbed with as little effort as possible and without urgency… You should climb the mountain in a state of equilibrium.” (Dr. Brahm Prakash’s counsel)

- “To live only for some unknown future is superficial. It is like climbing a mountain to reach the peak without experiencing its sides.”

- “I laid the foundation for Stage IV on two rocks—sensible approximation and unawed support. I have always considered the price of perfection prohibitive and allowed mistakes as a part of the learning process. I prefer a dash of daring and persistence to perfection.”

- “Within the next four months, we conducted 64 static tests. And we were just about 20 engineers working on the project!” (on RATO)

- “Leaders can create a high productivity level by providing the appropriate organizational structure and job design, and by acknowledging and appreciating hard work.”

- “I wanted men who had the capability to grow with possibilities… share their power with others and work in teams… take responsibility for slip-ups. Above all, they should be able to take failure in their stride and share in both success and failure.”

- “What makes a productive leader? … He should give appropriate credit where it is due; praise publicly, but criticize privately.”

- “If there is one thing outsiders dislike, it is unpleasant surprises. Good teams ensure that there are none.”

- “‘Know where you are going. The great thing in the world is not knowing so much where we stand, as in what direction we are moving.’” (epigraph quoted in the book while framing IGMDP)

- “[Prof. Sponder] told me that one should never worry about one’s future prospects: instead, it was more important to lay sound foundations, to have sufficient enthusiasm and an accompanying passion for one’s chosen field of study.”

- “A project team member must in fact act like a detective. He should probe for clues… and then piece together different bits of evidence to build up a clear, comprehensive and deep understanding of the project’s requirements.”

5. Critical analysis

Yes—through project-level details rarely present in political memoirs: dates (e.g., 21 Nov 1963 Nike–Apache), roles (integration, telemetry), costs (RATO unit costs), and explicit definitions (sounding rocket vs SLV vs missile). These ground the inspirational claims in operational engineering.

As autobiography, it’s unusually institutional: it shows how organizations grow by trust, cross-functional integration, and explicit learning loops. Sarabhai’s remark on project leaders as integrators is essentially a human-systems theory of complex engineering management.

6. Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths (pleasant/positive).

First, the granularity—from a leaking crane at T-minus minutes to the human chain lifting a rocket—creates skin-in-the-game texture. That sequence alone refutes the myth that breakthroughs require opulence; they require people who lift.

Second, the leadership anthropology—Sarabhai’s defense of Kalam as an “integrator,” Dhawan’s mentoring through grief, Brahm Prakash’s humility after SLV failure—offers a transferable playbook for any R&D lab: trust youth, integrate talents, normalize experiments, institutionalize compassion.

Third, the ethical ecology—insisting the Interim Test Range spare a bird sanctuary—models development without callousness.

Weaknesses (unpleasant/negative).

At times the hagiographic tone softens critique; e.g., institutional friction appears mostly as “contemptuous pride” to be overcome, but less as structural policy or procurement analysis (though costs are wonderfully specific).

Literary readers may also find the prose didactic—parables and scripture interleaved with engineering—though I found the blend refreshingly adult, not adolescent “STEM vs belief” polemics.

7. Reception, criticism, and influence

The book has remained a staple in Indian classrooms and reading lists, and Kalam’s status as Missile Man and later President of India (2002–2007) magnified its reach. Major outlets memorialized him as a scientist-educator whose books inspired youth; the national response to his death—state mourning, cross-party tributes—confirms the cultural staying power of the Wings of Fire ethos.

Universities Press continues to carry the title with world territorial rights, indicating sustained demand; library catalogs show the 1999 Hyderabad imprint is standard.

Critically, academics have discussed the memoir’s fusion of spirituality with scientific achievement, claiming it offers a psychologically protective framework for long-term, high-uncertainty projects—an interpretive lens you can feel in the book’s cadence.

8. Comparison with similar works

If you admired Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! for curiosity and Werner von Braun’s technical reminiscences for systems engineering, Wings of Fire sits closer to a nation-building memoir: less eccentric anecdote, more institutional ramp-up.

Compared to Homi Bhabha–centered narratives of India’s nuclear program or Satish Dhawan biographies, Kalam foregrounds young engineers, cost realism, and integrator-leadership.

It also contrasts with purely spiritual autobiographies—Kalam’s spirituality is ergonomically linked to creative work: prayer as a cognitive tool to “tap and develop” inner resources for problem solving.

9. Conclusion

I read Wings of Fire as both a personal compass and a professional manual. The compass part: “We are all born with a divine fire…”—not as metaphor, but as a reminder to convert attention into contribution. The manual part: define systems precisely (sounding rocket vs SLV vs missile), embrace trust-led leadership, track costs and capabilities obsessively, and protect the living world even as you build new tools.

Who should read this?

- Students and early-career builders seeking a motivational book grounded in real engineering.

- Managers of complex projects, who need examples of trust-based integration and experimentation.

- General readers open to a memoir that speaks fluently about both prayer and propellants.

Who might bounce?

- Readers who want literary experiment over institutional substance.

- Readers allergic to didactic, values-forward prose.