What if a film was not a story you watched, but a trance you entered?

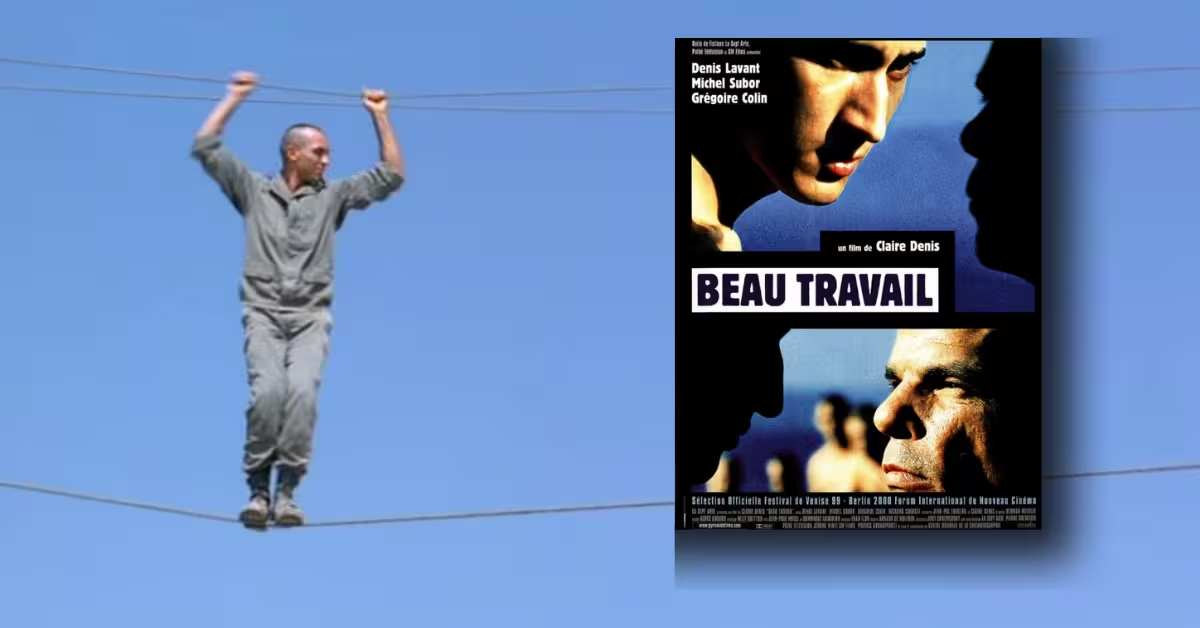

This is the central question posed by Claire Denis’s monumental 1999 film, Beau Travail. It is a cinematic poem, a languid and hypnotic work of art that seeps into your consciousness rather than announcing itself with a conventional plot.

Loosely based on Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd , Beau Travail transposes the maritime huis clos of the original story to the sun-scorched, arid deserts of Djibouti, where a company of French Foreign Legionnaires trains under a blistering, indifferent sky.

Through its mesmerizing visuals, minimalist dialogue, and a profound understanding of the human body in motion, the film explores the corrosive nature of jealousy, the fragility of masculinity, and the devastating consequences of repressed desire.

My overall impression of Beau Travail is one of awe. It is a film that defies easy categorization, a masterpiece of atmosphere and sensation that has rightfully earned its place as one of the greatest films of all time.

Of course. Here is an article on “Beau Travail” structured according to your precise specifications.

Table of Contents

Beau Travail: An Anatomy of Desire and Destruction

The final, shocking image of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail is not a moment of death but one of explosive, terrifying liberation. Sergeant Galoup, discharged and utterly alone, erupts into a frantic, ecstatic dance in his sterile Djibouti apartment to the corona discharge of “The Rhythm of the Night.”

This finale is not a literal event but a cathartic eruption of everything his body and soul have been forbidden to express. It is the shocking release of a repressed self, a final, violent burst of being before the implied silence of his fate.

This moment is the key to understanding the devastating truth behind the film’s depiction of military rituals. The precise drills and gruelling exercises in the sun-drenched landscapes are not merely about discipline or combat readiness; they are a form of sublimation, a rigid structure designed to contain and redirect primal human energies. The rituals become a language for the inexpressible, where camaraderie borders on intimacy and physical exertion becomes a proxy for emotional release.

This harsh beauty masks a silent turmoil, transforming the body into both a weapon and a prison.

The film’s power stems from its unique blend of dark reality and fictional genius. While not a direct true story, Beau Travail is deeply rooted in the authentic, mythologized world of the French Foreign Legion, an organization known for its brutal discipline and policy of erasing recruits’ past identities.

Claire Denis grafts this stark realism onto the ancient, moral framework of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor, transposing a tale of innocent beauty, obsessive envy, and cosmic injustice onto a modern military setting.

This fusion creates a potent tragedy.

It births the character of Galoup.

His narrative is a deep study of tragic obsession and a potential path to stunning redemption. Galoup’s obsession with the beautiful, natural, and beloved legionnaire Gilles Sentain is a poison born from his own inability to understand his desire and envy. His subsequent plot to eliminate Sentain is a act of profound self-destruction, a attempt to destroy the mirror that reflects everything he is not. His redemption, however, is not found in forgiveness but in the brutal honesty of his confession and the final, liberating dance, which acts as a purgatorial release from the strictures that doomed him.

In telling his story, Claire Denis exposes forbidden emotions with brutal honesty.

She frames the male body not as a symbol of power but as an object of gaze, of longing, and of aesthetic beauty.

Her camera lingers on the sweat, the muscle, the exhaustion, and the shared glances, visualizing the silent horror of repressed desire that fuels the entire tragedy.

This homoerotic tension is the silent engine of the plot, the unspoken truth that makes the military rituals both necessary and unbearably suffocating for Galoup.

Confronting this silent horror is what makes the film so psychologically potent and unsettling.

The film’s climax, the final dance, is arguably one of cinema’s greatest scenes because of its explosive meaning. Denis Lavant’s performance as Galoup channels a lifetime of repressed fury, jealousy, and longing into a violent, jerking, and ultimately transcendent physical outburst. It is a suicide of the self he was forced to be, a breakdown that is also a breakthrough. This scene recontextualizes the entire film, revealing that the strict discipline we witnessed was merely the surface tension over a boiling ocean of unexpressed emotion. It is the moment the body finally speaks its truth, and it is terrifying and beautiful in equal measure.

This astonishing adaptation not only reimagines Melville’s text but, for many, outshines the book.

It translates a nautical 19th-century moral parable into a visceral, sun-scorched 20th-century psychological drama, replacing Melville’s philosophical prose with Denis’s purely cinematic language of image and movement.

The uncomfortable truth that cemented the film’s masterpiece status is its refusal to provide easy answers or moral judgments.

It presents obsession, beauty, and cruelty as fundamental, intertwined forces of human nature, all set against the harsh military life that possesses its own unexpected beauty. The Djibouti landscape is both a brutal inferno and a breathtaking paradise, just as the legionnaires’ bodies are both instruments of discipline and objects of profound beauty. This duality is the heart of the film, finding the sublime in the severe and capturing the human spirit flickering defiantly within the most rigid of structures.

It is a flawless, painful, and liberating work of art.

The Plot of Beau Travail

The narrative of Beau Travail is a ghost, a memory reassembled from fragments.

We begin not in the heat of Africa, but in the cool, gray melancholy of Marseille, with the film’s narrator and tragic heart, Adjudant-Chef Galoup (Denis Lavant). He is a man displaced, writing his memoirs after being dishonorably discharged from the only life that gave him meaning: the French Foreign Legion. His words, spoken in a world-weary voiceover, guide us back to his past in Djibouti, a time of rigid order, profound purpose, and the beginning of his undoing.

Galoup’s world in Djibouti is one of ritual and repetition. He is a master of this world, a sergeant who drills his men with an exacting, almost obsessive precision under the command of Commandant Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor).

The relationship between Galoup and Forestier is immediately established as complex and deeply hierarchical. Galoup both admires and resents his commander, cherishing a wristband bearing Forestier’s name as a relic of a man he can never truly be—a man who is effortlessly respected and loved by his soldiers.

The life is spartan and masculine, a closed system of sweat, discipline, and shared hardship, punctuated only by Galoup’s occasional visits to a local Djiboutian girlfriend, where they dance in dimly lit clubs.

This carefully constructed world, built on control and suppression, is poised for a cataclysm.

The catalyst arrives.

He comes in the form of Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin), a new recruit whose quiet confidence and natural goodness immediately set him apart.

Sentain is not insubordinate, but he possesses an innate grace and a sense of self that Galoup, for all his authority, painfully lacks. The other legionnaires are drawn to Sentain’s effortless charisma and heroism, as seen when he rescues a fellow soldier from a helicopter crash. For Galoup, this admiration is a poison. He develops an immediate, irrational hatred for the young man, a dark obsession that he vows will lead to Sentain’s destruction. The film masterfully portrays this burgeoning jealousy not through overt confrontation, but through lingering glances, subtle shifts in posture, and the tightening of Lavant’s jaw.

The conflict in Beau Travail is a slow-burning fire. It first sparks into a visible flame during a cruel training exercise where a soldier is forced to dig a hole in the desert until he collapses. When Sentain, in an act of simple humanity, offers the suffering man his canteen, Galoup explodes.

He confronts Sentain, knocking the water from his hands, an act of pure, pointless cruelty. It is here that the film’s central conflict is laid bare: the rigid, sterile order of Galoup’s world cannot tolerate the intrusion of genuine compassion. The disciplined machine of the Legion is threatened by a single act of kindness.

This confrontation sets in motion an irreversible chain of events.

Sentain, in a moment of righteous anger, strikes Galoup.

For Galoup, this is the justification he has been waiting for, the final proof of Sentain’s insubordination that allows him to enact his vengeance under the guise of military discipline. He drives Sentain far out into the salt flats, a vast, white, alien landscape, and abandons him with a compass he has secretly sabotaged.

Galoup orders him to walk back to the base, a death sentence masquerading as a punishment. It is a moment of chilling, calculated evil, the culmination of his festering obsession.

The camera lingers on Sentain’s solitary figure shrinking against the immense, shimmering heat of the flats, a beautiful man condemned to a desolate, agonizing death.

But the world outside Galoup’s control intervenes. Sentain, after collapsing from dehydration, is discovered and rescued by a group of local Djiboutians who find him near their salt caravan. He is saved, but he never returns to the Legion, and is officially listed as a deserter.

Back at the base, the truth slowly surfaces when Sentain’s broken compass is found in the sand. Commandant Forestier, a man whose quiet wisdom Galoup could never comprehend, understands immediately what has happened. Without fanfare or fury, he confronts Galoup, not with accusations, but with a simple, damning judgment: Galoup is to be sent back to France to face a court martial, his career in the Legion over.

The system Galoup weaponized has turned against him, and his expulsion is swift and absolute.

This is the end of Galoup’s story in Africa, but not the end of the film. We return to his lonely apartment in Marseille, to the man stripped of his uniform, his rank, and his purpose. In a scene of profound despair, he meticulously makes his military-style bed, a final, futile act of the discipline that once defined him. He then lays down on top of it, clutching a pistol to his chest, seemingly preparing for suicide.

He reads the tattoo on his chest, a motto of a life he failed to live up to: “Serve the good cause and die”. The screen fades, leaving us with the impression of a tragic, self-inflicted end. But Denis has one final, electrifying surprise.

The film does not end with a gunshot. Instead, in what film scholar Erika Balsom has called “perhaps the best ending of any film, ever,” the screen explodes with light and sound.

We are in a nightclub, and Galoup, alone on the dance floor, begins to move to the pulsing beat of Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night”. He dances with a wild, convulsive, and utterly liberating energy—a breathtaking explosion of the life he had repressed for so long.

It is a dance of rage, of grief, of freedom, a final, ambiguous gesture that could be interpreted as a death spasm, a final fantasy, or a genuine moment of ecstatic release before forging a new life. It is a conclusion that offers no easy answers, only a profound and unforgettable image of a man finally, and perhaps tragically, free.

Analysis of Beau Travail

Claire Denis’s genius in Beau Travail lies in her ability to communicate complex psychological and thematic ideas almost entirely through visual language.

1. Direction and Cinematography

This film is the epitome of what critics call a “cinema of sensation.”

Denis is less interested in telling a story than she is in creating a mood and exploring a state of being. Her direction is patient and observational, focusing on the textures of skin, the shimmer of heat off the desert sand, and the rhythmic, ritualistic movements of the soldiers. As Denis herself said, the cast performed real Legion exercises together every day, and when set to the music of Benjamin Britten, “those exercises became like a dance”.

The cinematography by Agnès Godard is nothing short of breathtaking. The camera seems to physically caress the male form, lingering on the glistening, muscular backs of the legionnaires as they train. Godard’s lens captures both the stunning, expansive beauty of the Djibouti landscape and the claustrophobic intensity of the men’s inner lives.

The visual palette is bleached and sun-drenched, creating a world that feels both real and dreamlike, a perfect backdrop for the mythic tragedy unfolding within it.

2. Acting Performances

The performances in Beau Travail are remarkable for their physicality and restraint.

Denis Lavant delivers a tour-de-force performance as Galoup. With very little dialogue, he communicates a universe of internal conflict through his rigid posture, his tightly controlled movements, and the flicker of envy and rage in his eyes. His body is a vessel of repression, making his final, explosive dance scene all the more powerful.

Michel Subor, reprising a character name from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le petit soldat, brings a quiet, weary gravity to the role of Commandant Forestier. He is the film’s moral center, a man who understands the complexities of his men in a way Galoup never can.

Grégoire Colin is perfectly cast as Sentain; he embodies a natural, unforced goodness that is both angelic and deeply human, making him a believable catalyst for Galoup’s obsessive hatred.

3. Script and Dialogue

The screenplay, co-written by Denis and Jean-Pol Fargeau, is a model of minimalist perfection.

Dialogue is sparse, often functional, and reveals little of the characters’ inner thoughts. The heavy lifting is done by Galoup’s poetic, melancholic voiceover, which provides a philosophical framework for the visual narrative. The script’s true strength lies in its structure—the way it trusts the audience to piece together the story from images, gestures, and mood.

By stripping away extraneous plot and dialogue, Denis and Fargeau distill Melville’s story to its allegorical core. The pacing is deliberately slow, even languid, which might test some viewers but is essential to the film’s hypnotic effect. It forces the audience to stop looking for plot points and instead immerse themselves in the film’s sensory world.

4. Music and Sound Design

The use of music in Beau Travail is masterful and deeply symbolic.

The score is dominated by excerpts from Benjamin Britten’s 1951 opera, which is also based on Billy Budd[. The soaring, dramatic, and often tragic tones of the opera lend an epic, mythic quality to the soldiers’ mundane training rituals. It elevates their physical exertions into something profound, a ballet of masculine striving.

This classical score is brilliantly juxtaposed with the diegetic music of the Djibouti nightclubs and, most famously, with the final scene’s use of “The Rhythm of the Night.” This final musical choice is a stunning masterstroke. It shatters the film’s somber, operatic mood and catapults Galoup—and the audience—into a completely different emotional space, one of raw, ecstatic, and modern energy.

The sound design is equally effective, emphasizing the natural sounds of the desert: the wind, the crunch of boots on sand, and the strained breathing of the men.

5. Themes and Messages

Beau Travail is a rich text that explores a multitude of profound themes.

The most prominent theme is a critique of a certain kind of rigid, repressive masculinity. The French Foreign Legion is presented as a hyper-masculine world, one that attempts to channel aggression and desire into disciplined ritual. Galoup is the ultimate product of this system, a man whose identity is entirely subsumed by his role. Sentain’s arrival, with his inherent self-possession and compassion, represents a different, more fluid form of masculinity that the system cannot contain and that Galoup must destroy.

The film is also saturated with a powerful, unspoken homoeroticism. The camera’s gaze on the male body is undeniably sensual, and Galoup’s obsession with Sentain is coded not just as professional jealousy, but as a dangerously repressed desire. His hatred is the twisted, violent manifestation of an attraction he cannot acknowledge or process.

The film is a powerful exploration of how desire, when denied, can curdle into destruction. Furthermore, the setting in post-colonial Djibouti adds another layer of meaning.

The presence of the French Legionnaires, performing their strange, pointless rituals in a land that is not their own, speaks to the lingering, ghostly presence of colonialism and the existential emptiness at its heart.

Comparison to Other Works

The most obvious point of comparison for Beau Travail is its source material, Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor. Denis brilliantly transposes the core allegorical conflict—the destruction of innate goodness (Billy/Sentain) by a tormented authority figure (Claggart/Galoup) under the watch of a compromised leader (Captain Vere/Forestier)—from the claustrophobic confines of a British warship to the expansive emptiness of the African desert.

However, Denis radically shifts the focus. While Melville’s story centers on the tragic fate of the innocent Billy, Denis’s film is almost entirely focused on the tormented inner world of the antagonist, Galoup, making it a profound character study of the destroyer, not the destroyed.

In its deliberate pacing and focus on landscape as a reflection of psychological states, the film shares a kinship with the work of directors like Michelangelo Antonioni or even Terrence Malick. Yet, its unique blend of tactile sensuality, elliptical storytelling, and political subtext makes it a singular work that has few direct peers. It stands as a unique monument in cinematic history.

The Rules of the Game

While both are French cinematic masterpieces critiquing social structures, they differ vastly. Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939) is a sprawling, tragicomic satire of the pre-WWII aristocracy, exposing hypocrisy through intricate plotting and deep focus.

Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1999) is a minimalist, poetic adaptation focusing on the repressed homoeroticism and destructive rituals within the French Foreign Legion, told through visceral imagery and body language.

Renoir dissects a collapsing society, while Denis explores the internal landscape of repressed desire.

Audience Appeal and Critical Reception

Beau Travail is not a film for the casual viewer seeking straightforward entertainment.

It is a demanding piece of art-house cinema that rewards patient, attentive viewing. It will undoubtedly appeal to cinephiles, students of film, and anyone interested in challenging, thought-provoking cinema that pushes the boundaries of narrative. Its slow pacing might be seen as a weakness by some, but for its intended audience, it is an essential part of its hypnotic power.

Upon its release, the film was met with widespread critical acclaim, especially in the United States. It topped the prestigious Village Voice Film Critics’ Poll in 2000. Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader deemed it a “masterpiece”, while J. Hoberman wrote that it was “so tactile in its cinematography, inventive in its camera placement, and sensuous in its editing that the purposefully oblique and languid narrative is all but eclipsed”. This acclaim has only grown over time. On Metacritic, it holds a score of 91 out of 100, indicating “universal acclaim”, and on Rotten Tomatoes, it has an 87% approval rating.

In the 2022 Sight and Sound critics’ poll, a once-a-decade survey of the greatest films ever made, Beau Travail was ranked as the 7th best film of all time, a testament to its enduring power and influence.

Personal Insight: The Enduring Rhythm of Beau Travail

More than two decades after its release, Beau Travail feels more relevant than ever.

It is, at its core, a film about the violent collapse of rigid systems. Galoup represents an old world order—patriarchal, colonial, militaristic—that defines itself through control, repression, and the exclusion of anything it perceives as “other.” His obsession with Sentain is the desperate lashing out of a man who senses his own irrelevance in the face of a newer, more humane way of being.

In this light, the film is a powerful allegory for our contemporary struggles with outdated models of masculinity, the legacies of colonialism, and the ways in which institutions built on dominance inevitably destroy themselves from within.

Galoup’s tragedy is that he is trapped by the very ideology that gives him power. He is a gatekeeper of a hyper-masculine world that ultimately offers him no emotional sustenance, no room for vulnerability, and no language for desire. When confronted with Sentain’s simple, unthreatening goodness, his only recourse is to annihilate it. This is a dynamic we see played out repeatedly in society, where fear of the “other”—whether based on race, sexuality, or ideology—leads to violence and repression. The film serves as a timeless warning about the poison of envy and the profound danger of a life lived without self-knowledge.

But it is that final, transcendent scene that offers a glimmer of a different path. The dance is an act of pure, anarchic expression. As Erika Balsom writes, in that moment, Galoup “inhabits a utopia of movement without rules”. It is a profound statement about the possibility of liberation.

Perhaps, Denis suggests, the only way to break free from the prisons we build for ourselves is not through intellectual understanding or political action, but through the raw, untamed, and glorious power of the body itself—through finding, at the end of all things, the rhythm of the night.

Quotations

Given the film’s sparse dialogue, its most powerful “quotes” are often visual moments or lines from Galoup’s narration:

- Galoup’s Narration on His Fate: “I know they’re right. The Legion, Forestier, the court martial… And I’m right too.”

- Galoup’s Narration on Forestier: “He had something I lacked. I know that now. He was a leader of men. He knew how to love them.”

- Galoup’s Tattoo: “Sers la bonne cause et meurs” (“Serve the good cause and die”).

- The Final Dance: The explosive, non-verbal climax to “The Rhythm of the Night” serves as the film’s ultimate, unforgettable statement.

Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Breathtaking Cinematography: Agnès Godard’s visual work is hypnotic, tactile, and masterful.

- Powerful Central Performance: Denis Lavant’s physical portrayal of Galoup is a tour-de-force of repressed emotion.

- Profound Thematic Depth: A rich and layered exploration of masculinity, desire, and colonialism.

- Masterful Use of Music: The juxtaposition of Britten’s opera and pop music is brilliant and unforgettable.

- A Singular Artistic Vision: A truly unique and uncompromising film that stays with you long after it ends.

Cons:

- Deliberately Slow Pacing: The film’s languid rhythm may be challenging for viewers accustomed to faster-paced narratives.

- Oblique Storytelling: The elliptical and non-linear plot requires significant audience interpretation.

- Emotional Coldness: The detached, observational style can create a sense of emotional distance for some viewers.

Conclusion

Beau Travail is a cinematic masterpiece, a work of profound and haunting beauty. It is a film that confidently rejects conventional storytelling in favor of creating a powerful sensory and emotional experience. Claire Denis crafts a devastating portrait of a man destroyed by his own repressed nature and the rigid ideology of the world he inhabits.

It is a challenging, hypnotic, and ultimately unforgettable film that solidifies Claire Denis’s place as one of the most vital and visionary directors of her generation. For those willing to submit to its unique rhythm and poetic language, Beau Travail is an absolute must-watch, a truly transcendent piece of cinema.

Rating: 5/5 Stars