Doubt (2008) is a gripping psychological drama that explores the unsettling grey areas between certainty and suspicion, morality and manipulation.

Directed by John Patrick Shanley and based on his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, the film stars Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis in a tense, emotionally charged story set in a 1964 Bronx Catholic school. Doubt tackles controversial themes such as faith, authority, sexual misconduct, and institutional silence, delivering a narrative that challenges viewers to question their own assumptions about guilt, truth, and justice.

With powerhouse performances and a screenplay that thrives on ambiguity, Doubt (2008) remains one of the most thought-provoking films of its era, inviting audiences into a morally complex world where knowing the full story may be impossible.

Table of Contents

Introduction

What happens when your faith is shaken, not by blasphemy, but by suspicion? When certainty becomes a weapon and truth slips through the cracks of silence? Doubt (2008), directed by John Patrick Shanley, is not merely a movie—it is a moral confrontation draped in silence, shadow, and suspicion.

Adapted from Shanley’s own Pulitzer Prize–winning play Doubt: A Parable, this searing American drama takes place in a Catholic elementary school in the Bronx during the turbulent 1960s. With a powerhouse cast led by Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis, the film strips belief down to its trembling bones.

The brilliance of Doubt lies in its refusal to provide closure. And for me, it was personal. As someone who grew up questioning inherited truths, the film offered a mirror to those moments where moral clarity faltered—and I found myself desperately grasping for something solid in a fog of human fallibility.

In this long-form Doubt movie review, we’ll dive into the plot, performances, themes, and why this film remains a masterclass in ambiguity.

Plot Summary

Set in 1964, Doubt (2008) begins in a church in the Bronx where Father Brendan Flynn (Philip Seymour Hoffman) delivers a homily on uncertainty—a subtle foreshadowing of the storm to come. He speaks of doubt not as weakness, but as the force that binds us in our shared struggle to believe.

Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Meryl Streep), the stern, hawk-eyed principal of St. Nicholas School, runs her domain like a military operation. Her beliefs are fixed, her suspicions constant, and her faith is rooted in tradition rather than grace. She represents an old-school Catholicism, deeply hierarchical, immovable, and sometimes weaponized.

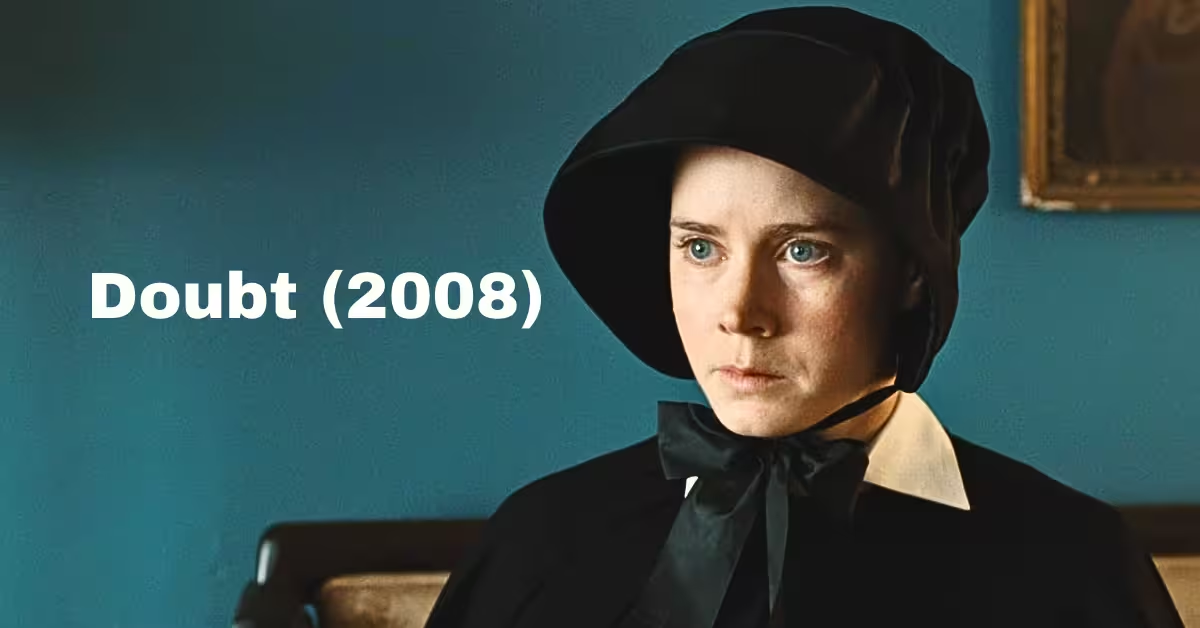

Sister James (Amy Adams), a sweet and idealistic young teacher, notices that Father Flynn has taken a particular interest in Donald Miller—the school’s only Black student and a vulnerable figure due to both his race and his implied sexuality. After Donald returns from a private meeting with Flynn visibly upset and smelling of alcohol, Sister James confides in Sister Aloysius.

Here begins the core tension of the film: Sister Aloysius becomes convinced that Father Flynn has abused Donald, although she possesses no concrete proof. What she does have, she claims, is “certainty.”

Flynn insists he’s innocent and explains that he discovered Donald drinking sacramental wine and was protecting him from harsh punishment. But Sister Aloysius is unconvinced. Their verbal battles become theological duels—between openness and rigidity, between progressive empathy and dogmatic authority.

The pivotal scene in Doubt arrives when Sister Aloysius meets Donald’s mother, Mrs. Miller (Viola Davis), whose performance—though brief—is devastating. Rather than reacting with outrage, Mrs. Miller pleads with Aloysius to let her son finish the year. Her husband beats him. Donald is already suffering, and Flynn, in her eyes, is perhaps the only adult who shows the boy kindness—even if it might be “that kind” of kindness.

This exchange complicates the narrative in a profoundly uncomfortable way. Mrs. Miller’s concern is not the moral high ground but survival and opportunity. Her reaction shifts the film from a simple moral whodunit into a complex story of competing truths and social power.

Aloysius eventually confronts Flynn directly. She claims to have contacted a nun at his former parish who confirmed his guilt. Flynn resigns from his position and leaves.

In the final scene, Sister Aloysius confesses to Sister James that she lied—she never contacted anyone. But she still believes he was guilty. Then, finally, in a moment that unravels her moral steel, she breaks down and says, “I have doubts… I have such doubts.”

That line haunted me.

And therein lies the genius of Doubt: the film doesn’t tell us if Father Flynn is guilty or not. It weaponizes ambiguity, making us confront our own assumptions, our need for answers, our desperate craving for moral clarity. It is, above all else, a film about the terrifying complexity of being human.

Direction and Cinematography

John Patrick Shanley, a playwright first and filmmaker second, makes his directorial approach in Doubt feel deeply theatrical—and I mean that as high praise. Rather than transforming the story into a cinematic spectacle, he allows the drama to simmer quietly within confined spaces. The result is an emotionally charged atmosphere that feels almost suffocating, forcing the viewer to confront characters as if seated in the front row of a stage play.

There’s a striking intimacy in how Shanley blocks his characters—particularly in scenes where power dynamics shift mid-conversation. The camera often lingers too long or swings just a second late, creating an unease that mimics the discomfort of unspoken suspicion. The claustrophobic interiors of the school and church, coupled with long pauses in dialogue, allow ambiguity to fester like a wound that refuses to close.

Then there’s Roger Deakins, the visual maestro behind the lens. His cinematography is almost its own character. Gray skies dominate the outdoor scenes, while shadows play a crucial role indoors. Light is seldom pure in Doubt; it often filters through cracked windows or illuminates only one face at a time. It’s a visual metaphor for the film’s central concern: no one ever sees the whole picture.

In one particularly symbolic shot, we see leaves blown wildly across a courtyard, the wind invisible yet undeniable. Like doubt itself, its presence is felt rather than seen. That shot lingered in my mind for days—it reminded me that even when you think you know, you’re often at the mercy of forces you can’t pin down.

Shanley’s direction is not flashy. It’s firm, elegant, restrained—and for a film about moral grayness, that’s exactly what it needed. It’s not here to entertain. It’s here to provoke, to stir something that most films shy away from: the ache of ambiguity.

Acting Performances

I can still hear Meryl Streep’s voice, cold and clipped, her eyes narrowed not just in judgment but in fear. As Sister Aloysius, Streep delivers a performance so controlled that every breath feels calculated. And yet, her final breakdown—“I have doubts”—cracks the steel, revealing the fragile soul beneath the habit. It’s not just acting. It’s an excavation of character.

Philip Seymour Hoffman brings an equally formidable presence to Father Flynn. His warmth, charisma, and vulnerability complicate our feelings toward him. Is he a predator? A protector? Both? His defensive posture during confrontations feels real, human, heartbreaking. That’s the power of his performance—you never feel like you’re watching a villain, even when you suspect he might be.

Amy Adams as Sister James is the film’s moral compass, a stand-in for the audience. Her eyes often glisten with tears, caught between loyalty and fear, between belief and uncertainty. It’s a delicate role, and Adams plays it with heartbreaking sincerity.

And then there’s Viola Davis. In a performance that spans only one extended scene, she detonates every expectation. Her character, Mrs. Miller, offers perhaps the most devastating emotional perspective in the entire film. Her tears aren’t cinematic—they’re maternal. Desperate. Real. Watching her struggle with the possibility of abuse but also the terrifying alternative—a violent father—was the emotional gut punch I never recovered from.

As Salon wrote, Davis delivers “a near-miraculous level of believability.” According to NPR, hers is “the film’s most wrenching performance,” and Roger Ebert believed she deserved an Oscar. I agree.

Together, this cast turns Doubt into an ensemble triumph. Every glance, pause, and vocal tremor adds texture to a world that feels terrifyingly real.

Script and Dialogue

“Doubt can be a bond as powerful and sustaining as certainty.”

That line from Father Flynn’s opening sermon sets the tone for the entire screenplay—and what a screenplay it is. Shanley’s adaptation of his own stage play is an exercise in precision. The words are lean but heavy, like bricks. You feel their weight even when they’re whispered.

What stands out is how little is actually said about the central issue. No character names the crime aloud. Instead, the script dances around it—invoking suspicion, morality, faith, and fear without ever confirming or denying the truth. That restraint is genius.

The dialogue between Flynn and Aloysius reads like intellectual warfare. There are no easy victories, no dramatic mic drops. Just two people fighting for their version of justice, armed with words, emotion, and instinct.

The pacing is deliberate, slow-burning, but never boring. Shanley gives space for silence—those deadly, pregnant pauses where uncertainty festers. And those moments, I believe, are where the real writing lives.

Music and Sound Design

Howard Shore’s score is hauntingly sparse. Known for his grand orchestral work in The Lord of the Rings, here Shore goes minimal, using subtle strings and lingering piano chords to underscore the tension without overpowering it.

The music doesn’t instruct you how to feel—it invites you to question what you’re feeling. That, in itself, is rare.

Sound design, too, plays a quiet role in building tension. The rustle of a habit, the echo of footsteps in a hall, the low hum of wind outside stained-glass windows—each sound sharpens the unease.

This isn’t a film where music swells to tell you you’ve reached an emotional high. This is a film that stares at you in silence until you can’t take it anymore.

Themes and Messages

At its core, Doubt is not about whether Father Flynn is guilty. It’s about what happens to people—communities, churches, entire societies—when certainty becomes a weapon.

It explores how doubt, while uncomfortable, is essential. Without it, we’re left with zealotry. With it, we find humility.

The film also engages deeply with themes of institutional power, race, gender, and moral authority. Donald Miller’s status as the only Black student, and possibly a gay child in a Catholic institution, heightens the stakes. His mother’s heart-wrenching plea reveals the intersection of societal cruelty and maternal survival.

Sister Aloysius represents an authoritarian system—unquestioning, cold, morally rigid. But by the end, her very soul is cracked open by doubt. That transformation isn’t just dramatic. It’s spiritual.

According to scholar Daniel Cutrara, the film operates as a metaphor for worldwide crises involving priest abuse allegations. That’s what makes Doubt tragically timeless: it resonates just as loudly in today’s world as it did in 2008.

Comparison (Optional but Insightful)

When placed alongside similar films dealing with moral ambiguity and institutional tension, Doubt (2008) holds a distinct and haunting resonance. It calls to mind Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men (1957), where the search for truth is as much about the accuser as it is the accused. Yet unlike that film, Doubt offers no resolution—only reflection.

It also echoes the thematic intensity of Spotlight (2015), another film centered around the Catholic Church and abuse allegations. But while Spotlight relies on investigative journalism to unveil truth, Doubt operates in the shadows of what cannot be proven. That contrast is important: it shifts the burden from external evidence to internal conviction.

Director John Patrick Shanley’s previous screenplays, including Moonstruck, lean more into romantic and whimsical territory. Doubt is his starkest, coldest, and most provocative work—akin to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible in its exploration of hysteria, power, and righteous certainty.

What sets Doubt apart, though, is how it thrives on tension without requiring a payoff. It is content with discomfort. In an industry obsessed with clarity and closure, this film is a bold act of resistance.

Audience Appeal and Reception

Doubt is not for casual viewers seeking entertainment. It’s a film for thinkers—those who engage with film as an extension of philosophy, ethics, and theology. Cinephiles, critics, educators, and anyone who has questioned authority (especially religious) will find much to contemplate here.

Despite its theatrical roots, it performed solidly at the box office—grossing $50.9 million against a $20 million budget. That success was buoyed by critical acclaim and its prestige cast.

The film has a 79% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a 68/100 on Metacritic, signaling generally favorable reviews. Audiences praised the writing, performances, and emotional weight.

And yet, Doubt did something rare: it sparked moral dialogue long after the credits rolled. Viewers walked away debating not just who was right—but what “right” even means.

Personal Insight: Why Doubt (2008) Still Matters

Few films have ever made me examine my own worldview like Doubt. Raised in a system that worshipped certainty, I recognized myself in Sister James—wide-eyed, soft-spoken, aching for simplicity. But as I grew older, I became Sister Aloysius in my own life—questioning authority, pushing back, driven by intuition even when I lacked proof.

And now? I find myself in the space between.

This movie makes that space real. It validates it. In an age of tribalism, polarization, and binary thinking, Doubt (2008) reminds us that the most honest position might be the most painful: not knowing.

It’s also deeply relevant to contemporary issues—be it whistleblowing, institutional abuse, or the courage it takes to confront power. Its lesson isn’t just religious. It’s universal.

As Roger Ebert once said, “Shanley leaves us doubting.” And that, I believe, is the film’s greatest achievement.

Quotations

- “Doubt can be a bond as powerful and sustaining as certainty.”

- “You haven’t the slightest proof of anything!” – Father Flynn

- “I have doubts… I have such doubts.” – Sister Aloysius

- “In the pursuit of wrongdoing, one steps away from God… but in His service.”

- “The truth makes for a bad sermon. It tends to be confusing and have no clear conclusion.”

These lines pierce deeper than any revelation. They encapsulate the philosophical backbone of the film.

Pros and Cons

Pros:

- 🔥 Tour-de-force performances by Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Viola Davis, and Amy Adams

- 🧠 Intellectually rich, morally provocative narrative

- 🎥 Masterful cinematography by Roger Deakins

- ✍️ Exceptionally written dialogue with powerful subtext

- 🎭 Oscar-nominated ensemble chemistry

Cons:

- 🐢 Slow pacing might test casual viewers

- 🤐 Lack of closure may frustrate audiences craving resolution

- 🎭 Stage-like staging can feel static for some moviegoers

Conclusion

Doubt (2008) isn’t about the truth. It’s about how we search for it—and the cost of believing without proof. It offers no easy answers, and that’s what makes it unforgettable.

With unforgettable performances, razor-sharp writing, and a directorial hand that respects the audience’s intelligence, this film is a meditation on faith, fear, and the frightening limits of certainty. It deserves to be revisited, taught in classrooms, and whispered about in late-night conversations.

I walked into this film expecting drama. I left with a tremor in my chest and questions that still echo today.

A must-watch for fans of powerful, thoughtful cinema.