Last updated on July 2nd, 2024 at 04:02 pm

The relationship between nature and human health is profoundly related.

Numerous scholarly researches illustrate that regular exposure to natural environments can meaningfully enhance both mental and physical well-being. Exposure to nature has been shown to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, while also improving mood and cognitive function. Spending time in natural surroundings can lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol and increase feelings of happiness and relaxation.

Additionally, physical activity in green spaces, such as parks and forests, promotes cardiovascular health, helps control obesity, and enhances overall fitness.

Additionally, the presence of urban green spaces is crucial for public health. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that accessible green areas in cities encourage physical activity and social interaction, both of which are essential for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. However, the unequal distribution of these green spaces across socio-economic groups highlights a significant public health challenge, as lower-income communities often have less access to nature, exacerbating health disparities and underlining the need for more inclusive urban planning.

Exposure to nature has been shown to have a profound impact on our health, both physically and mentally. Numerous studies highlight the benefits of spending time in natural environments, suggesting that such exposure can improve overall well-being in several ways.

Today, in rapidly growing urbanization the beauty of pristine nature and wilderness disappearing with it. The new generations of urban people have been developing a taste of synthetic beauty where the modern consumerist products are taking their place away from nature.

The dominance of electricity, people’s longing for artificial beauty over natural, domesticated cultivation of nature and increasing thirst for a material obsession that comes with financial success make us distant from Mother Nature every moment. Can man-made craftsmanship take the place of nature? Are we causing our own destruction by going away from nature and natural? For humankind’s fate hovers around the questions

like ‘Is it the scientific and technological flourishing that we ought to place value on or as a whole to the nature that provides us with unadulterated peace, happiness, and subsistence in the long run”?

Nature, people, survival and health are always knitted together from the time immemorial. All other species, except humankind, still maintain a close tie with it. Time and time again it has been proven to be an antidote, strong palliative and invaluable source of mental stability. The bond and camaraderie of humankind with nature have always been counted as the most valued one.

It is as if in using the facility of language, the thing we believe most separates us from nature, we are constantly pulled back to it– our origins. But the hope is still alive around the corner. An unusual picture of the cities across Bangladesh has been experienced this spring as they were left alone like deserted cities. Holidays and weekends were taken advantage of by the city dwellers who sought tranquillity far from urban mechanical movement. Have people started to realise the worth of nature finally?

The Demands For Green Space and Nature

The definition of Green Urban Areas includes public green areas used predominantly for recreation such as gardens, zoos, parks, and suburban natural areas and forests, or green areas bordered by urban areas that are managed or used for amusement purposes.

World Health Organization’s Urban Green Spaces and Health says it all. It says the connection between green space and health has been recognized throughout history, and was one of the driving forces behind the urban parks movement of the 19th century in Europe and North America. According to its another finding on urban planning, environment and health published in 2010 states that green spaces can positively affect physical activity.

At the Fifth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) in Parma, Italy (2010), the Member States of the WHO European Region pledged “…to provide each child by 2020 with access to healthy and safe environments and settings of daily life in which they can walk and cycle to kindergartens and schools, and to green spaces in which to play and undertake physical activity”.

The publication says, “Improving access to green spaces in cities is also included in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 11.7, which aims to achieve the following: “By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities”.

The review adds that “the effects of green spaces on physical activity and their potential to reduce public health inequalities. Access to public open space and green areas with proper recreation facilities for all age groups is required to support active recreation,” as “studies have provided evidence of multiple benefits from urban green space, through various mechanisms, and with potentially differential impacts in various populations.”

Benefits of Nature in General

As is well-known already, access to green space may produce health benefits through various pathways some of which may have a cooperative effect. WHO proposed various health effects of exposure to green space and green areas:

- it improves relaxation and restoration as nature and green space contain restorative mental health benefits. The study claims that nature does in two ways: a) it reduces psycho‐physiological stress as contact with nature (e.g. views of natural settings) can have a positive effect on those with high levels of stress, by shifting them to a more positive emotional state; and b) it restores attention by drawing our attention to interesting and rich stimuli in natural settings which helps to improve performance in cognitively demanding tasks.

- It improves social capital by fostering social interactions and promoting a sense of community. They found an association between the quantity and, even more strongly, the quality of streetscape greenery and perceived social cohesion at the neighbourhood scale.

- Exposure to greenery improves the functioning of the immune system as the report indicates that the studies on Japanese have demonstrated associations between visiting forests and beneficial immune responses, including expression of anti‐cancer proteins which suggest that immune systems may benefit from relaxation provided by the natural environment or through contact with certain physical or chemical factors in the green space.

- While physical inactivity is identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, exposure to green space enhances physical activity, improves fitness and reduces obesity.

- While due to continuing urbanization, rising traffic volumes, industrial activities, and a decreasing availability of quiet places in cities, green space provides anthropogenic noise buffering and production of natural sounds promoting human health. Evidence suggests that a well‐designed urban green space can buffer the noise, or the negative perception of noise, emanating from non‐natural sources, such as traffic, and provide relief from city noise.

Reduction of the urban heat island effect review indicated that urban greenery, including parks, street trees and green roofs, mitigates Urban Heat Island effects

- Greenery or nature enhances pro-environmental behaviour, the “behaviour that consciously seeks to minimize the negative impact of one’s actions on the natural and built world”. The WHO recommends that external stimuli, like experiencing natural environments promote pro-environmental behaviour; and “exposure to nature may increase cooperation and sustainable intentions and behaviour with the suggestive proof that that childhood experiences in nature appear to enhance adult environmentalism meaning that “If pro-environmental actions are widely adopted, people can contribute to substantially reducing carbon emissions.

- Nature Improves mental health and cognitive function, as studies of green spaces and health have demonstrated stronger evidence for mental health benefits, and for stress reduction, compared with other potential pathways to health. An Australian study has shown perceived neighbourhood greenness to be more strongly associated with mental health than with physical health.

Nature reduces cardiovascular morbidity as a study in the United Kingdom suggests an association between low quantities of neighbourhood green space and elevated risk of circulatory disease.

Exposure to nature was found to be associated with reduced prevalence of type 2 diabetes and reduced mortality. Evidence that exposure to urban green space is linked to reduced mortality rates is accumulating. Moreover, findings in Japan reveal that the five‐year survival rate in individuals aged over 70 was positively associated with having access to more space for walking and with parks and tree‐lined streets near the residence.

Nature And Human Health

The way nature helps us cure is known as “Wilderness therapy” which is a further emerging treatment intervention which uses a systematic approach to work with adolescents with behavioural problems. Although this is not the only group that can be benefited from the outdoors, wilderness therapy is most often used with young people at risk to help them address any emotional, adjustment, addiction or psychological problems.

According to The World Health Organization (WHO), health is ” A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

The definition implies a person’s physical, mental, and social condition and affirms health as multidimensional which includes physical, psychological, social and environmental factors. According to researchers from the Institute for Housing and Urban Research, Uppsala University, Sweden, “it implies that people can enjoy relatively good health or suffer relatively poor health in different ways at the same time.”

For example, a person who is physically and mentally fit may still have relatively poor health because he or she is socially isolated or the target of discrimination. Being fit does not mean being healthy. Philip B. Maffetone and Paul B. Laursen differentiate the two in the article Athletes: Fit but Unhealthy?

The American Psychological Association discusses the benefits of nature for mental health, underscoring how exposure to natural environments can reduce stress and improve mood and cognitive function. They say, spending time in nature can act as a balm for our busy brains. Both correlational and experimental research have shown that interacting with nature has cognitive benefits.

The preventive work can aim at positive as well as negative aspects of human-environment relations. For example, environmental health professionals can promote health not only by identifying and removing toxic agents but also by identifying salutary features of environments, including possibilities for experiences of nature.

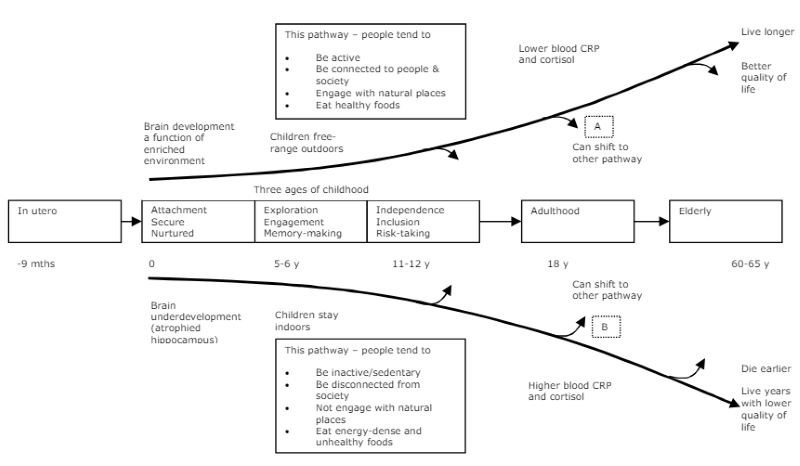

However, infant mortality rates have fallen over half a century from new health problems such as mental health disorders and obesity because of physical inactivity and distant relations with nature. The scientific literature now suggests that there are three distinct ages of childhood during which there are different needs and thus differing implications for adult behaviour and public policy.

The Relationship Between Children and Nature

Open green space and access to nature are both important for children, with the quality of their environmental exposure inextricably linked to their well-being. The outdoor environment is perceived as a social space which influences children’s choice of informal play activities and promotes healthy personal development.

Furthermore, children’s relationship with nature is a fundamental part of their development, allowing opportunities for self-discovery and natural environmental experience. However, access to high-quality natural environments is unequally distributed across social groups.

- 1. First Age of childhood (0 to 5 years) – this is when attachment, security, and nurture are most important. The parental sphere of influence is dominant, and so relations between parent and child are vital for children’s development.

- 2. Second Age of Childhood (6 to 11 years) – this is when memories are first laid down in continuous narratives. Children engage more outside the parental sphere of control and explore their environments to make memories and develop cognitive capacities.

- 3. Third Age of Childhood (12 to 18 years) – this is when children increasingly disengage from parents as they seek both independence (from existing structures) and inclusion (in peer social networks) when more risks are taken, and the limits of the world tested.

The interaction between the environment and children’s physical activity is complex. Physical activity is strongly related to both the fitness and the fatness of children, as well as cognitive development. Both fitness and fatness track into adulthood where they become risk factors for metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease and early mortality. More physically active children are likely to have better behaved in the classroom.

Through outdoor exploration, nature allows for unstructured play, generating a sense of freedom, independence and inner strength which children can draw upon when experiencing future incidents of stress.

There is, therefore, growing evidence to show that children’s contact with nature and consequents’ levels of physical activity affects not only their well-being but also their health in later life. A bunch of researchers from the University of Essex suggest a funnel of pathways within which all our lives are shaped. At the top, people live longer with a better quality of life; at the bottom, they die earlier and often live years with a lower quality of life. On the healthy pathway, people tend to be active, be connected to people and society, engage with natural places, and eat healthy foods.

As a result, they tend to have higher self-esteem and better mood, be members of groups and volunteer more, keep learning, engage regularly with nature and be more resilient to stress.

Children’s lack of experience with the environment and nature gave rise to a phenomenon known as the ‘extinction of experience’, whereby children are experiencing nature far less than ever before in history. As a consequence, they are unfamiliar with nature’s many components.

This suggests a need to establish good behaviours early. Engagement with wild nature secures positive adult outcomes. A visit to woodland as a child increases the number of visits made as an adult. Play affects brain development. Outdoor activity has a positive effect on long-term memory, and cognitive development is influenced by free play and exploration.

Being able to recognise and name something is a prerequisite to forming a bond with it and, thus, caring about it. As a result of their lack of familiarity with the natural components, they act less to protect the species with which they are unfamiliar, and further species loss and environmental destruction can continue unnoticed and unabated. This downward spiral of disconnection and disassociation can begin in childhood and continue through adulthood, meaning that the habit of being and not being with nature actually develops at an early age.

Health Benefits of Green Spaces in Urban Areas

Researchers from the Univesity of Essex UK found that “Many of the drivers pushing individuals towards the unhealthy lower pathway are very recent in human history: consumption of unhealthy foods, increasing inactivity, atomization of families and communities, and disengagement from nature.”

A group of researchers from Norway and Sweden add that, “Experiencing or viewing nature both play an important role in positively influencing our health and wellbeing. It is well-known that physical activity improves both physical and mental health”. Green space is important for mental well-being, and levels of interaction/engagement have been linked with longevity and decreased risk of mental ill-health in Japan, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands.

According to WHO’s Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health 2010, Physical inactivity (lack of physical activity) has been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality (6% of deaths globally). Moreover, physical inactivity is estimated to be the main cause of approximately 21–25% of breast and colon cancers, 27% of diabetes and approximately 30% of ischaemic heart disease burden.

WHO says the physical inactivity is causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths worldwide. When it is a significant risk factor for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as stroke, diabetes and cancer. Less and less physical activity is occurring in many countries. Globally, 23% of adults and 81% of school-going adolescents are not active enough

Pre-industrial humans spent 1000 kcal on activity per day, whereas for modern humans the average is only 300 kcal (kilocalorie) expended. Researchers from McMaster University Maureen Dobbins at el, Canada found that “Inactivity increases the likelihood of obesity, and reduces life expectancy. Such physical inactivity is known to track from childhood, and is a key risk factor in many chronic diseases of later life”.

Watching TV for considerably an excessive amount of time; electronic devices such as smartphones, computers and gaming devices; fewer distance-travelled by cycle or on foot, excessive dependence on vehicles for mundane movements are the causes of the death of physical activities or frequent visitation to nature that involves physical movement.

It is now well-established that exposure to natural places can lead to positive mental health outcomes, whether a view of nature from a window, being within natural places or exercising in these environments.

With its astonishing technological advances in modern life, it has also led to rapid changes in ways of living that have pervasive health outcomes. Research findings reveal that “dietary habits of the populations have so been changed that obesity has within a generation risen in incidence to take it from 3-6% of adult populations to more than 25% in many industrialized and developing countries. Furthermore, less time spent outdoors in green spaces has resulted in drops in ecological knowledge and understanding, as well as having negative effects on mental health”.

The unorganised traditional games that include a lot of moving around, are now changing into sitting in front of your private computer playing computer games. The most active physical activities include skiing, hiking, climbing trees, enjoying water activities and soccer in the fields.

The natural environment represents dynamic and rough play spaces that challenge motor activity in children. The topography, like slopes and rocks, affords natural obstacles that children have to cope with. The vegetation provides shelter and trees for climbing. The meadows are for running.

The prevalence of adolescent problem behaviour has steadily increased with drug, tobacco and alcohol abuse, aggressive and anti-social behaviour, violence, teenage pregnancy and suicide rates becoming growing problems.

“In addition, the importance of vitamin D obtained from being outdoors in the sunshine has recently been identified as playing a role in long-term health. Humans depend on exposure to the sun for the synthesis of adequate amounts of vitamin D. Lack of vitamin D has long been recognised as causing rickets in children, as well as exacerbating osteoporosis and even osteomalacia in adults. More recently it has been recognised that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased risks of some cancers, cardiovascular disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and type I diabetes, with possible links to type II diabetes and schizophrenia.”

The research titled More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment by Gerd Kempermann et al, reveals that “rats and mice have shown that those raised in enriched environments have more hippocampal neurons and better memories.

In early childhood, social conditions are vital. Scandinavian research demonstrates that factors such as children’s social play, concentration and motor ability are all positively influenced following play in nature. This was particularly apparent in a study involving children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Children worked better and their concentration improved after participating in activities in green surroundings.

Louise Chawla University of Colorado Boulder writes “that children usually prefer open spaces with trees compared to barren ones that lack nature, and they are found to be more creative in plays and were seen to spend more time with adults and engage in social development.

Saraha E. Pilgrim et al Study have shown a strong correlation between ecological knowledge and the frequency of visits to green spaces. In the past local ecological knowledge was taught in schools. Today, however, global environmental issues such as climate change and regional biodiversity loss take precedence in the school curriculum over local species and habitats. Are we at risk of training a generation of ecologists able to predict slight global shifts but unable to notice the decline of sparrows in their garden?

Natural environments are varied and changeable and so provide greater opportunities for free explorative play. Indeed this type of unstructured play gives greater opportunities for decision-making while at the same time promoting creative, diverse and imaginative play, which are all seen as important elements of a child’s personal and cognitive development.

Society has become increasingly risk-averse for young children, and this may mean a whole generation is condemned to poorer quality later lives. This suggests that the whole community should be encouraged to recognize the value of having children and young people spend time outside. If children are over-supervised, they will be prevented from taking risks and thus will learn less about a potentially dangerous world. Risk-taking is about learning limits. If today’s children cannot learn about taking risks, where will the country’s entrepreneurs come from in the future?

Time spent in ‘wild’ nature such as hiking and playing in the woods has been shown to have more positive long-term effects on children than time spent in ‘domesticated’ nature such as picking flowers, and planting seeds or trees. It has been suggested that the structure of ‘domesticated’ outdoor activities may hinder the experience by not allowing for “extensive, spontaneous engagement with nature” and so do not have such a profound influence on the individual. Spending time in wilderness environments enabled young people to connect with nature and connectedness-to-nature scores steadily increased over the duration of the project.

Two researchers Nancy M Wells and Kristi S Lekies from Cornell University, USA, explored the relationship between childhood that experiences nature and the urban children who have chances to opportunities to enjoy the domesticated natural environment.

Titled Nature and the Life Course: Pathways from Childhood Nature Experiences to Adult Environmentalism they say, “Adolescents who, as children, had more often played in wilderness areas were more likely to prefer a wildland walking path than those who had mostly played in the yard before the age of ten. Those who played in wilderness areas also had a greater tolerance for living without modern comforts when presented with a hypothetical scenario and had the greatest preference for outdoor occupations.

They add, “Associations between childhood foraging and later environmental knowledge. People who reported having foraged the greatest breadth of things—from acorns, arrowheads, and cattails, to fireflies, fish, and turtles—in childhood had, as teenagers, better knowledge of biodiversity, early life outdoor experiences and environmental attitudes in early adulthood”.

Their data on surveying undergraduate students indicated that appreciative outdoor activities, such as, time outdoors enjoying nature, consumptive outdoor activities, such as, hunting and fishing; media exposure, such as, books and television; and witnessing negative environmental events, such as, seeing a special outdoor area be developed during one’s youth were predictive of later life ecocentric versus anthropocentric beliefs. Two prior studies examine connections between childhood exposure to nature and adult attitudes about nature or plants, that children’s playtime in the natural environment as well as other experiences impact later life attitudes, knowledge, or behaviours regarding the environment. Other research examines the effects of more structured activities such as environmental education programs.

Mental ill-health brings stigma, prejudice and discrimination, and is known to be carried forward from childhood to adulthood. Positive mental health is not the same as a lack of ill health: it is about living life well. Positive emotions and well-being improve health and long-term survival. Positive mood increases serotonin, and green exercise improves mood.

The sense of positivity is related to self-esteem. Self-esteem and mood are important indicators of current and future well-being and therefore affect the life pathways of both adults and children. Self-esteem is a determinant of short- and long-term psychological well-being. It refers to a positive or negative attitude towards self and is an evaluation of a person’s sense of worth or value.

It is commonly accepted as a key indicator of emotional stability and is thus a contributor to mental well-being, quality of life and survival. High self-esteem is related to security and closeness in relationships which helps to foster social connectedness.

Young people with high self-esteem are less susceptible to peer pressure and alcohol abuse and perform better at school, and adolescents with high self-esteem are less vulnerable to bullying. By contrast, low self-esteem is closely linked to mental illness and the absence of psychological well-being. Individuals exhibiting low self-esteem often show signs of self-rejection, self-dissatisfaction and self-contempt.

An individual’s level of self-esteem also has implications for health behaviours, motivations and lifestyle choices. High levels of self-esteem are associated with healthy behaviours, such as healthy eating, participating in physical activities, not smoking and lower suicide risk. High self-esteem is also associated with positive qualities such as independence, adaptability, leadership, stress resilience, life satisfaction, social adjustment and greater academic and work achievements.

Some work reflects concerns that urbanization, environmental degradation, and lifestyle changes are quantitatively and qualitatively diminishing possibilities for human contact with nature. For example, dense urban settings, if poorly designed (without accessible green space), may reduce opportunities for stress-reducing nature contact as well as increase exposure to environmental stressors. Other work considers nature as just one aspect of the physical environment that is potentially beneficial for health. For example, epidemic obesity in some countries has focused attention on sedentary lifestyles and environmental supports for physical activity, including but not limited to nearby parks.

The mere presence of trees encourages more frequent use of the outdoor space and experiencing nature reduces mental fatigue, diminishes sensations of stress and has positive effects on mood. This raises a question as to why we do not do this routinely in the planning of settlements.

Trees and forests affect human health in a variety of ways. They help to preserve people’s health by maintaining air quality, by providing nutritious foods and medicinal substances, and by protecting homes, crops and vital infrastructure from intense sunlight, high winds, and flooding. They also challenge health by discharging pollen, harbouring disease-bearing insects, and posing hazards from fire and falling objects. In addition to such physical and biochemical influences, trees and forests affect health in ways that primarily have to do with people’s behaviour and experiences. For example, surveys in numerous countries have found that many people like to visit natural areas such as forests and that they do so to relax and ease feelings of tension.

Domesticated urbanised natural environments are no way comparable to nature. Moreover, in order to maintain a healthy physiological, psychological state, and for long healthy life the nurturing, fostering, cultivating and promoting green plants and vegetation have not alternative. Instead of a financial promotion, economic prosperity frequent visitation to nature helps us grow and grow wise with natural phenomenon. Knowing nature, living in nature, consuming natural, promoting nature and contemplation on nature have the sweetest payoff and long-lasting rewards.

Conclusion

Incorporating more nature into daily life can lead to significant health benefits.

Whether through simple activities like walking in a park, gardening, or participating in outdoor sports, making time for nature can improve physical health, reduce stress, and enhance mental well-being. Encouraging the integration of natural elements in urban environments and promoting nature-based therapies can further support public health initiatives.

References

- Book chapter: Health Benefits of Nature Experience: Psychological, Social and Cultural Processes by Terry Hartig et al.

- WHO: Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health 2010

- Nature, Childhood, Health and Life Pathways by Jules Pretty et al.

- What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or “modernization”? by Ashley Fox, Wenhui Feng and Victor Asal

- Nature and its Influence on Children’s Outdoor Play by Kellie Dowdell, Tonia Gray and Karen Malone

- Benefits of Nature Contact for Children by Louise Chawla

- Nature and the Life Course: Pathways from Childhood Nature Experiences to Adult Environmentalism by Nancy M. Wells and Kristi S. Lekies

- WHO: Urban green spaces and health

- Athletes: Fit but Unhealthy by Philip B. Maffetone and Paul B. Laursen