Last updated on September 2nd, 2025 at 02:25 pm

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein is a groundbreaking work that explores the ways in which subtle changes in the way choices are presented, or “choice architecture,” can significantly influence human behavior.

The book introduces the concept of “libertarian paternalism,” which advocates for policies that nudge individuals towards making better decisions for themselves without restricting their freedom of choice.

By blending insights from behavioral economics, psychology, and policy, the authors demonstrate how nudging can be effectively used to improve decision-making in areas ranging from personal finance and healthcare to environmental sustainability and public policy.

Thaler and Sunstein offer compelling examples and practical applications, proving that small, well-designed changes can guide people towards better choices without sacrificing their autonomy.

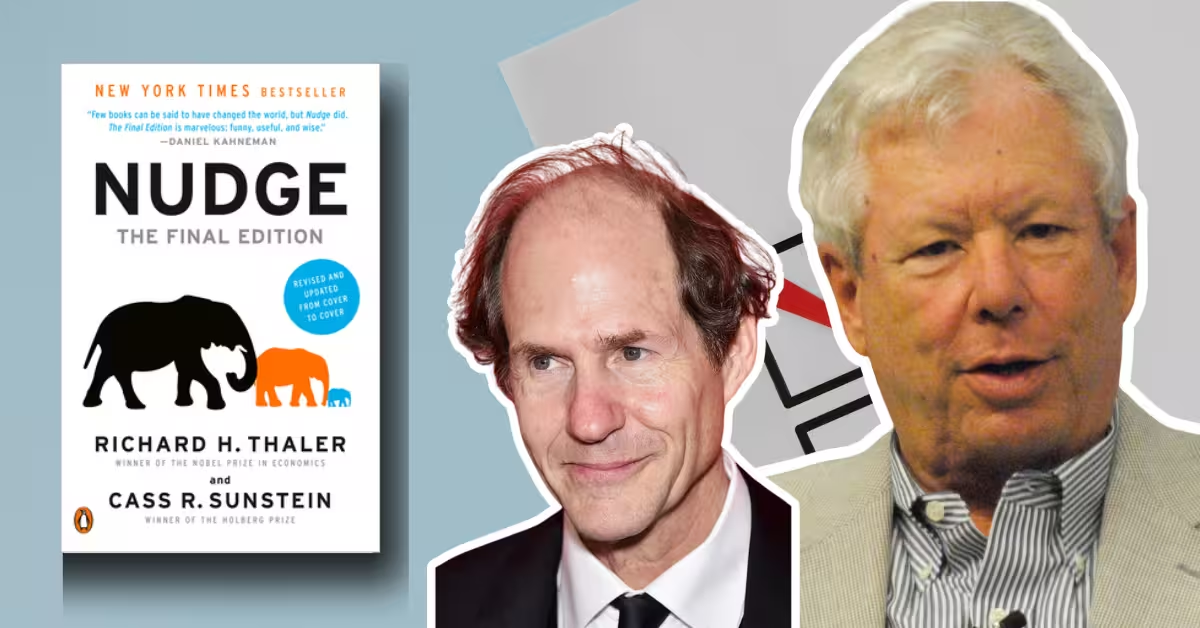

When I first read Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, I wasn’t just intrigued — I was quietly revolutionized. Richard H. Thaler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, and Cass R. Sunstein, a distinguished professor at Harvard Law School, weave an intellectually gripping narrative grounded in behavioral economics and psychology. The book is not just theory; it is an elegant manifesto for libertarian paternalism—a term that at first sounds paradoxical, but slowly reveals its practical genius.

Published by Yale University Press in 2008 and later revised in 2021 as The Final Edition, Nudge isn’t merely a scholarly read; it’s an armchair guide to smarter living. It addresses a fundamental human paradox: we want to make good decisions, yet we often don’t. Why? Because our brains are fallible, influenced by biases, heuristics, and the “architecture” of the choices presented to us.

At its core, the book argues:

“A nudge…is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives”.

Table of Contents

Background: The Authors and Their Context

Nudge, written by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, explores the concept of “libertarian paternalism,” where people are nudged toward making better choices without restricting their freedom to choose.

The book examines how small, strategic changes in the way choices are presented—referred to as “choice architecture”—can have a significant impact on improving decisions in areas like health, finance, and society, all while preserving individual freedom. Through various examples, the authors demonstrate how these “nudges” can help people make better decisions that align with their long-term interests, without coercion or mandates.

The intellectual backbone of Nudge lies in the professional harmony between its authors. Richard Thaler, whose seminal research helped found the discipline of behavioral economics, and Cass Sunstein, a constitutional scholar and behavioral policy expert, bring an unmatched confluence of economics and legal theory.

The book is structured around understanding human decision-making and the role of nudges in guiding people to better outcomes. It includes discussions on biases, the importance of defaults, the potential of smart disclosures, and how nudging is used in both private and public sectors to improve behavior.

Thaler and Sunstein aim to provide insights on how to design systems and policies that promote well-being, advocating for subtle yet effective interventions that respect individual choice.

Summary: Navigating the Mind’s Blind Spots

They build on decades of work, including insights from Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky—pioneers who shattered the myth of Homo economicus, the idea that humans are perfectly rational decision-makers. Instead, Thaler and Sunstein introduce a far more accurate depiction: Homo sapiens, flawed but improvable.

The book follows a thematic structure rather than a chronological or linear format. It’s divided into sections that explore cognitive biases, apply them to real-world domains, and suggest policy interventions using “nudges.”

Part I: Humans and econs

Central Premise

Part I of Nudge lays the philosophical and cognitive groundwork for the book’s core thesis: that humans are not the hyper-rational agents that classical economics (and much of public policy) assumes them to be. Thaler and Sunstein introduce a dichotomy between “Econs”, the idealized agents of economic theory, and “Humans”, the fallible beings studied by behavioral economists and psychologists.

“The distinction between Econs and Humans is the starting point for our book” (p. 6).

This section challenges traditional economic assumptions, introducing the reader to systematic human biases, the dual-system model of thinking, and the idea of libertarian paternalism, a gentle form of policy guidance that nudges people toward better choices without eliminating freedom of choice.

1. Humans vs. Econs: A Foundational Contrast

One of the primary intellectual moves in Part I is the drawing of a sharp contrast between Econs and Humans:

- Econs: These are the creatures of standard economic theory. They make logical decisions, consider all alternatives, and choose what maximizes their utility. They are consistent, calculating, and immune to cognitive bias.

- Humans: In contrast, humans are subject to heuristics and biases, inconsistencies, and influence by seemingly trivial factors like the order of options or the phrasing of a question.

The authors write:

“Econs can think like Einstein, store as much memory as IBM’s Big Blue, and exercise the willpower of Mahatma Gandhi. Humans, by contrast, have limited attention, are forgetful, and have imperfect self-control” (p. 7).

This recognition is not just academic; it forms the basis for an argument in favor of reshaping policy and environments to fit how people actually behave.

2. The Two Systems of Thinking

In an important cognitive turn, Thaler and Sunstein align their argument with insights from psychology and neuroscience—especially the dual-process model of cognition.

- Automatic System: Fast, intuitive, often emotional. This system allows us to respond quickly, but it’s also error-prone.

- Reflective System: Slower, deliberate, rational. It’s effortful but can catch the mistakes of the automatic system—when we use it.

“Humans have two cognitive systems—an Automatic System and a Reflective System—and the former often dominates” (p. 19).

This distinction explains why even intelligent, educated people make irrational decisions—because they’re often on cognitive autopilot. The key takeaway here is that choice environments must accommodate the realities of the automatic system if they are to be effective and humane.

3. What Is Choice Architecture?

This is where the key term choice architecture enters the scene.

A choice architect is “someone who has the responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions” (p. 3). From cafeteria managers choosing how to arrange food, to government officials designing tax forms, everyone engaged in structuring decisions is influencing behavior—intentionally or not.

Thaler and Sunstein’s genius lies in recognizing that neutral design is a myth. Since some design must exist, the authors argue we ought to use design intentionally to improve welfare.

“Small and apparently insignificant details can have major impacts on people’s behavior. A good rule of thumb is to assume that ‘everything matters’” (p. 3).

This line undergirds their central claim: nudges work precisely because design matters.

4. The Importance of Defaults

One of the most potent tools of the choice architect is the default option—what happens if the chooser does nothing.

The authors demonstrate this with powerful examples, like organ donation rates:

“In countries where people must opt in to be donors, the rate of donation is dramatically lower than in countries where people must opt out” (p. 34).

This stark difference—despite similar cultural attitudes—illustrates how defaults capitalize on human inertia and the automatic system. Nudges work not by changing hearts and minds, but by gently steering behavior through smarter design.

5. Libertarian Paternalism

Perhaps the most innovative and provocative concept introduced is libertarian paternalism. At first glance, the term seems oxymoronic: How can one be both a libertarian and a paternalist?

Thaler and Sunstein argue that it’s possible—and often desirable—to steer people’s choices in welfare-enhancing directions without restricting freedom.

“We strive to design policies that maintain or increase freedom of choice while also guiding people in directions that will improve their lives” (p. 5).

They reject coercion and insist that any nudge must be transparent, easy to opt out of, and motivated by the chooser’s own interests, not the architect’s.

This blend of ethics and behavioral science redefines the role of policymakers and marketers alike.

6. Real-World Implications and Ethical Guardrails

Part I ends by subtly asking a crucial question: If humans are fallible, who gets to decide what’s best for them? The authors are aware of the dangers of overreach and manipulation. They advocate for a humble, evidence-based approach—favoring nudges that are:

- Based on robust behavioral research.

- Designed with welfare and autonomy in mind.

- Subject to scrutiny and revision.

“Nudging is not about coercion… but about making it easier for people to make good decisions” (p. 6).

Conclusion

Part I of Nudge is a masterclass in interdisciplinary synthesis. It blends behavioral psychology, economics, ethics, and public policy into a compelling call to rethink how we influence decisions.

The authors position nudging as a humane and effective alternative to both laissez-faire neglect and heavy-handed regulation. By recognizing the limitations of the human mind, the power of defaults, and the moral obligations of choice architects, Thaler and Sunstein provide not just critique, but a path forward.

In sum, the key messages are:

- Humans are not Econs; we’re error-prone and irrational in systematic ways.

- Choices are never presented neutrally; the architecture always influences outcomes.

- Nudges can correct for cognitive biases without sacrificing freedom.

- Policymakers must embrace libertarian paternalism: guiding choices while preserving liberty.

Part II: The Tools of The Choice Architect

The Architecture of Influence

In Part II, Thaler and Sunstein move from theoretical exposition to applied behavioral engineering. If Part I answers why people err in their decisions, Part II addresses how those decisions can be improved—without coercion, only by design.

At the heart of this discussion is a central assertion:

“Every environment in which people make choices is filled with nudges, whether intentional or not” (p. 89).

This means that every website, cafeteria, tax form, or health plan is an instance of choice architecture, and its design profoundly affects individual behavior and decision-making.

The authors stress that this is not a call for manipulation, but rather an appeal to conscious and responsible design. Their approach is rooted in libertarian paternalism, where freedom of choice remains paramount, but context is optimized for better outcomes.

Chapter 4: When Do We Need a Nudge?

Here, Thaler and Sunstein ask: Under what conditions are nudges most necessary and effective? They argue that nudges are especially vital in situations characterized by:

- Benefits now, costs later (e.g., overeating, smoking).

- Decision-making that’s infrequent (e.g., choosing a mortgage).

- Limited feedback (e.g., climate-related behaviors).

- Complex choices with many variables (e.g., health insurance plans).

- Poorly understood consequences (e.g., saving for retirement).

The authors state:

“Nudges are most helpful when people have trouble translating their choices into outcomes they care about” (p. 74).

In such cases, even the reflective system—the slow, deliberate part of our minds—may be overwhelmed. Meanwhile, the automatic system tends to take over, often relying on biases, shortcuts, or even inaction.

Chapter 5: Choice Architecture

This pivotal chapter outlines six key principles of choice architecture that can be wielded to improve outcomes through subtle but powerful nudges.

1. Defaults

“Never underestimate the power of inertia” (p. 83).

Defaults are perhaps the most potent tool of all. Whether it’s automatic enrollment in retirement plans or opt-out organ donation systems, defaults often govern real-world behavior simply because people stick with the status quo. This is where nudge theory shines: changing a default can shift millions of decisions without restricting freedom.

2. Expect Error

The authors champion an error-tolerant design, suggesting:

“Humans make mistakes. A well-designed system expects its users to err and is as forgiving as possible” (p. 84).

Airplane cockpits, for example, are engineered to prevent pilots from retracting landing gear during takeoff. In public systems—like financial forms or safety protocols—choice architects should embed safeguards anticipating user confusion.

3. Give Feedback

Timely, understandable feedback improves decision-making. Thaler and Sunstein offer the example of energy bills that include neighborhood comparisons:

“If people learn they are using more energy than their neighbors, they tend to cut back” (p. 86).

This simple nudge relies on social comparison—another human heuristic—but redirects it for beneficial outcomes.

4. Understand Mappings

Consumers often struggle to relate choices to their consequences. For example, many can’t translate a car’s fuel efficiency rating into long-term cost. The authors recommend designing tools that “translate attributes into evaluable dimensions” (p. 89), such as expressing fuel costs in dollars per year rather than miles per gallon.

5. Structure Complex Choices

In domains like Medicare, health plans, and investing, choices are daunting. Choice architects should aid by simplifying options or breaking them down into manageable sub-decisions. They argue:

“When there are too many choices, people often make worse decisions—or none at all” (p. 91).

6. Incentives

While incentives are not nudges in the strictest sense, highlighting them can serve as a nudge. People often misinterpret or ignore incentives (such as long-term tax benefits), and well-designed choice architecture ensures these incentives are visible and salient.

Chapter 6: But Wait, There’s More

This chapter draws from marketing to show how presentation shapes behavior. Anchoring, framing, and priming are discussed not as gimmicks but as empirical nudging tools.

- A retirement plan’s matching contribution sounds more appealing as “free money” than a percentage-based incentive.

- Describing a surgery as having a 90% survival rate leads to more favorable reactions than saying it has a 10% mortality rate—framing at work.

- When consumers are primed with words like “clean” and “pure,” they behave differently—subconscious nudging.

“The way choices are framed can affect outcomes as much as the actual economic incentives involved” (p. 98).

This insight echoes Kahneman and Tversky’s foundational work on prospect theory: losses loom larger than gains, and framing a situation as a potential loss is often more persuasive.

Chapter 7: Smart Disclosure

Smart disclosure is a 21st-century solution to an old problem: information asymmetry. Thaler and Sunstein argue that modern institutions should not just disclose information, but make it usable.

“We call for institutions to disclose data in standardized, machine-readable formats that enable comparison, customization, and comprehension” (p. 104).

The authors call these tools “choice engines”, digital platforms that personalize and simplify decision-making in fields such as finance, nutrition, and health insurance.

For example:

- A website that lets you compare cell phone plans based on your actual usage.

- A food scanner app that flags allergens based on your personal medical profile.

🕸️ Chapter 8: #Sludge

In a departure from the uplifting tone of most nudge discussions, Chapter 8 introduces the concept of sludge—the evil twin of nudging. Where nudges aim to help people make better choices, sludge consists of friction, confusion, and opacity deliberately introduced to impede action.

“Sludge is any friction that makes it harder for people to obtain benefits to which they are entitled or to make good choices” (p. 111).

Examples include:

- Confusing paperwork that discourages welfare enrollment.

- Complex unsubscribe procedures in email marketing.

- Endless clicks required to cancel a subscription.

The antidote to sludge? Clear, simple, and accessible design. The authors call on both public and private institutions to conduct sludge audits, rooting out unnecessary barriers.

Summary: Design With Dignity

Part II is a blueprint for real-world reform. It affirms that people are not weak or stupid—but they are predictably human. The architecture surrounding their decisions should respect their limitations and enhance their agency.

Key insights include:

- Nudges work best when people face rare, complex, or high-stakes choices.

- Defaults, feedback, and framing are subtle but profound tools.

- Smart disclosure empowers people with usable information.

- Sludge is not just annoying; it’s ethically wrong and often regressive.

As the authors note:

“Choice architecture is not about controlling people. It’s about helping them” (p. 88).

This is where libertarian paternalism reaches its practical apex—not by telling people what to do, but by making it easier for them to do what they already want to do.

Part III: Money

Overview

In this section, Thaler and Sunstein demonstrate how flawed human decision-making leads to suboptimal financial behavior in both the short and long term. They argue that most people do not save enough, borrow too much, and misunderstand how insurance works. These behaviors are not merely the result of ignorance or irresponsibility, but of predictable cognitive biases and poor choice architecture.

The solution? Design financial systems that nudge people toward better decisions—systems that respect individual liberty, reduce friction, and take advantage of human psychology rather than fight against it.

“If we want to help people make better choices with their money, we must pay close attention to the details of choice architecture” (p. 121).

This is where the brilliance of libertarian paternalism becomes evident: people remain free to choose, but better-designed environments guide them to more beneficial choices.

Chapter 9: Save More Tomorrow™

In this seminal chapter, Thaler and Sunstein present one of their most influential contributions to behavioral finance: the Save More Tomorrow™ (SMarT) program.

The Problem:

People do not save enough for retirement. Traditional solutions—such as lectures on compound interest or financial literacy—often fail to produce lasting change.

The Insight:

Most people have good intentions to save more but lack the willpower to act on them. Moreover, when people get raises, they don’t automatically increase their savings rates.

The Solution:

Design a nudge that aligns with human behavior:

- Automatically enroll employees in a plan to increase their savings rate with every raise.

- Make the plan opt-out, not opt-in.

- Ensure it’s framed as preserving current lifestyle, since increases occur only when income rises.

“Save More Tomorrow exploits three principles: inertia, loss aversion, and mental accounting” (p. 128).

This simple plan more than tripled average savings rates over time. It is a prime example of how a small change in choice architecture can lead to dramatic improvements in financial behavior—without coercion or mandates.

Chapter 10: Do Nudges Last Forever? Perhaps in Sweden

Here, Thaler and Sunstein examine the Swedish national retirement plan, launched in 2000. Citizens could either:

- Choose their own investment portfolios from a vast menu of over 450 funds.

- Or allow the government to place them into a default option called The Premium Savings Fund.

What Happened:

Initially, two-thirds of participants actively chose their own funds. The government encouraged this through a marketing campaign that framed choice as a sign of civic engagement and financial literacy.

But over time, that pattern reversed.

“By 2007, only about 10 percent of new participants were making active choices” (p. 133).

The authors note that people reverted to inertia—the power of the default option ultimately prevailed.

The key takeaway is nuanced:

- Nudges can be long-lasting, especially when inertia and defaults are used skillfully.

- However, choice architecture must be adaptive; early enthusiasm may not last, and framing matters.

Chapter 11: Borrow More Today: Mortgages and Credit Cards

This chapter addresses America’s most pressing financial concern: consumer debt. The authors dissect how poor choice architecture, confusing disclosures, and psychological blind spots contribute to high levels of indebtedness.

Cognitive Biases in Borrowing:

- Present bias: people value immediate gratification over future costs.

- Over-optimism: borrowers believe they’ll pay off the balance next month.

- Framing effects: minimum payment suggestions serve as anchors, encouraging people to pay less than they should.

“When credit card bills include a ‘minimum payment,’ many people view that as a suggested payment—not a floor, but a target” (p. 139).

The Nudge:

Change the framing. In the UK, regulators required companies to disclose how long it would take to pay off a balance if only minimum payments were made. This nudge significantly increased monthly payment amounts.

In the case of mortgages, the authors criticize interest-only loans and teaser rates, which obscure the true cost of borrowing. They propose Smart Disclosure tools to demystify the borrowing process, such as online calculators and personalized comparisons.

Chapter 12: Insurance: Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff

Insurance is a realm where misunderstood probabilities and fear-based framing distort financial decisions. Thaler and Sunstein focus on the prevalence of deductible anxiety and over-insurance.

Common Errors:

- People buy extended warranties they don’t need.

- They over-insure against minor losses (e.g., cracked smartphones).

- They underinsure against catastrophic risks (e.g., disability).

“People will buy insurance for a \$150 loss, but not for a \$150,000 one” (p. 144).

This irrational behavior is driven by:

- Availability bias: Recent vivid losses loom large.

- Loss aversion: People feel losses more intensely than gains.

- Framing: Insurance is often pitched emotionally rather than statistically.

The Nudge:

Redesign insurance disclosures to:

- Emphasize expected value, not anecdotes.

- Use plain language and side-by-side comparisons.

- Encourage consumers to bundle risk, rather than fragment it.

One powerful policy nudge suggested: require insurers to show how much a policy costs per dollar of expected payout. This would reveal that many small policies are terrible deals.

Summary: Financial Freedom through Design

Part III: Money demonstrates that poor financial decisions are rarely the product of carelessness—they are the outcome of predictable flaws in human cognition and bad choice environments. From saving to borrowing to insuring, people are up against complexity, time pressure, and their own cognitive biases.

The antidote is clear:

- Use defaults, framing, and smart disclosure to simplify complex choices.

- Design with the automatic system in mind—don’t rely on perfect reasoning.

- Apply nudges that preserve freedom while enhancing well-being.

As the authors note:

“The ideal nudge is cheap to implement, easy to ignore, and powerful in its effect” (p. 147).

With Save More Tomorrow, Sweden’s public fund, better credit disclosures, and rationalized insurance plans, Thaler and Sunstein offer tangible, research-tested solutions. At every turn, they stay faithful to libertarian paternalism: improving decisions without ever eliminating choice.

Part IV: Society

Overview

In Part IV, Thaler and Sunstein shift focus from the individual to society at large. They apply the principles of nudging, behavioral economics, and libertarian paternalism to pressing civic concerns: organ donation, environmental sustainability, and public engagement.

The central insight remains unchanged: human decisions are shaped by context, biases, and defaults. But in these domains, the consequences of poor decision-making are not just personal—they affect communities, institutions, and even planetary survival.

“If we want to improve society, we must design social policies that are compatible with human nature” (p. 153).

In these chapters, choice architecture becomes a tool not only for helping individuals, but for building a more ethical, sustainable society.

🩺 Chapter 13: Organ Donations: The Default Solution Illusion

This chapter confronts a profoundly ethical and logistical challenge: how to increase organ donation rates. The scarcity of donor organs leads to thousands of preventable deaths annually. Thaler and Sunstein reveal that a seemingly trivial design element—the default—can dramatically alter outcomes.

The Behavioral Problem:

Even though many people support organ donation, they never get around to signing up.

“Inertia is powerful, especially when the action requires paperwork, discomfort, or moral uncertainty” (p. 154).

The Empirical Insight:

- Opt-in systems (e.g., U.S., Germany): Individuals must actively choose to donate. Result: Low participation.

- Opt-out systems (e.g., Austria, Sweden): Everyone is presumed to be a donor unless they object. Result: Extremely high participation—often over 90%.

“Austria and Germany are similar in culture and geography, but Austria’s organ donation rate is nearly double Germany’s. The difference lies entirely in the default” (p. 155).

Clarification:

The authors do not support presumed consent. This is a critical correction to previous misunderstandings. Instead, they advocate for:

The Nudge: Mandated Active Choice

Require people to decide—no default. When renewing a driver’s license, for instance, they must answer yes or no to organ donation.

“We believe that individuals should be asked to make a choice, but not forced in either direction” (p. 157).

This design respects liberty, eliminates inertia, and elevates personal responsibility. It embodies libertarian paternalism at its most elegant: nudging citizens to engage thoughtfully without overriding autonomy.

Chapter 14: Saving the Planet

Perhaps the most urgent application of choice architecture is in the battle against climate change and environmental degradation. Thaler and Sunstein argue that behavioral tools—nudges—can and should play a pivotal role in advancing sustainable behavior.

The Behavioral Landscape:

- Climate change is complex, long-term, and abstract.

- The automatic system discounts future harms.

- Individual actions seem inconsequential (“What difference does my recycling make?”).

“Humans are not wired to deal well with distant, probabilistic, and impersonal harms” (p. 165).

Behavioral Failures:

- Present bias favors driving over walking.

- Energy use is invisible and poorly understood.

- Feedback is rare or absent.

- Social norms may encourage consumption.

Key Nudges for Sustainability:

1. Feedback Nudges

Make energy use visible and comparative.

“When people are told that their neighbors use less energy, they reduce their consumption” (p. 167).

This “social comparison” nudge was tested in a randomized trial by power. The result? Significant reductions in household electricity use, especially among the most wasteful users.

2. Default Green Options

Make sustainable choices the default.

- Hotels: Automatically launder towels every third day unless guests request otherwise.

- Utilities: Enroll customers in green energy by default, with the option to opt-out.

3. Smart Disclosure

Help consumers compare carbon footprints or environmental impacts.

“If we label food with greenhouse gas scores, many consumers will nudge themselves toward lower-emission diets” (p. 170).

4. Fun and Gamification

Injecting play into sustainability increases engagement.

“When subway stairs were turned into piano keys in Stockholm, 66 percent more people chose the stairs” (p. 173).

This ingenious nudge leverages immediate feedback and intrinsic motivation—making the right choice not just ethical, but enjoyable.

Behavioral Insights Across Society

The broader argument is that societal outcomes often suffer because institutions are not designed for actual human behavior. Whether it’s policymakers underestimating inertia or agencies failing to communicate clearly, the mismatch between real minds and institutional systems is profound.

Nudges can fix this mismatch, with little cost, minimal risk, and often enormous benefit.

“Most people support environmental protection, safer streets, and helping others. But unless we make it easy, they will not act” (p. 165).

Ethical Anchors

As in previous parts, Thaler and Sunstein stress freedom of choice. Even in matters of public importance, they reject coercive mandates or deception. Their approach is:

- Transparent.

- Easy to opt out of.

- Respectful of individual variation.

“The goal is to align individual actions with both personal and societal values—without ever taking choice away” (p. 178).

This is particularly important in domains like organ donation and environmentalism, where moral intensity can tempt heavy-handed policies. Instead, the authors insist that gentle nudges—if designed well—can achieve broad compliance with greater legitimacy.

Cognitive Principles Revisited

Throughout Part IV, we see repeated references to core behavioral mechanisms:

- Defaults: Changing what happens if people do nothing.

- Framing: Presenting options in ways that change perception.

- Inertia: People’s tendency to stick with the status quo.

- Social norms: The influence of peers and neighbors.

- Limited attention: Making the invisible visible.

These levers—deeply rooted in dual-system thinking (automatic vs. reflective)—are not just private tools. They are levers of collective transformation.

Summary: Designing a Better Society

Part IV: SOCIETY shows that the stakes of choice architecture extend far beyond personal finance or daily decisions. Nudges can save lives, protect the planet, and activate public morality—all without heavy-handed intervention.

Key takeaways:

- Mandated choice offers a powerful middle ground in organ donation.

- Feedback and social comparison dramatically improve environmental behavior.

- Defaults and framing work even in civic contexts.

- Ethical design must always respect freedom and transparency.

As Thaler and Sunstein conclude:

“Better governance comes not from more rules, but from smarter design. Nudges don’t command—they invite. And the best of them help us become who we want to be” (p. 182).

Part V: The Complaints Department

Overview

In this section, Thaler and Sunstein confront the philosophical, political, and practical objections to nudging. They understand that nudges, despite being gentle, noncoercive tools, provoke concern. Is this manipulation? Can governments be trusted? What about autonomy? Is paternalism ever justifiable?

By addressing these questions directly, the authors not only reinforce their ethical foundations but also reveal the resilience and flexibility of the libertarian paternalist framework.

“If we are right, and people make mistakes, shouldn’t someone try to help them, as long as it’s done in a way that preserves freedom?” (p. 185)

They invite scrutiny, offer clarification, and provide evidence that good nudging is not only benign—it is often necessary.

🧭 Chapter 15: Much Ado About Nudging

This final chapter is structured around seven major criticisms commonly directed at nudge-based policy. For each, the authors offer a clear, evidence-based, and ethically sound rebuttal. Let’s examine them one by one.

❌ 1. “Nudging is Manipulative”

Perhaps the most emotionally resonant critique is that nudges amount to covert influence. If people are not aware that their behavior is being steered, does this violate their autonomy?

Thaler & Sunstein’s Rebuttal:

- Nudges should be transparent and public.

- They advocate what they call publicity: if a nudge cannot be defended in the public square, it shouldn’t be used.

- Many nudges (e.g., placing healthy food at eye level) are no more manipulative than setting a thermostat.

“Good nudges are like good architecture—they invite, not compel. And like good architecture, they’re visible to all” (p. 186).

Nudges do not bypass the reflective system entirely; they just make the better option easier to choose.

2. “Who Decides What’s Best for People?”

This is a foundational concern: can bureaucrats, academics, or politicians really know what’s good for us? What if they’re wrong?

Rebuttal:

- Choice architects exist already—there’s no such thing as a neutral design.

- The question isn’t whether someone will influence your choice, but how and with what intent.

- Nudging is simply about doing it better—with evidence and ethics.

“Every design nudges; we propose to nudge with care” (p. 188).

They also remind us that opt-out policies are still choices. Defaults can always be overridden.

3. “Nudging Undermines Freedom”

A classic libertarian argument: even subtle influence may reduce autonomy.

Rebuttal:

- No options are removed.

- People can opt out easily.

- Freedom to choose is sacrosanct in libertarian paternalism.

“If freedom means anything, it means the right to ignore a suggestion” (p. 190).

Nudges are thus framed as guidance, not governance—like signs pointing to a path, not walls blocking others.

4. “Slippery Slope to Coercion”

Some fear that non-coercive nudges will inevitably lead to coercive mandates.

Rebuttal:

- There is no evidence of such slippage.

- In fact, nudging is offered as an alternative to bans, mandates, or taxes.

- Governments that nudge well tend to regulate less, not more.

They quote legal scholar Cass Sunstein:

“Nudges are the least intrusive policy tools—so why not try them first?” (p. 192).

The slippery slope argument lacks real-world data and rests on abstract fear.

5. “People Will Become Passive or Dependent”

Could nudges weaken personal responsibility by making decisions too easy?

Rebuttal:

- Nudges support better decision-making, not replace it.

- In fact, mandated choice (as with organ donation) actively encourages responsibility.

Thaler and Sunstein believe well-designed environments enhance agency by enabling people to act on their own values more effectively.

6. “Nudging Doesn’t Work, or Backfires”

This is an empirical concern: are nudges really effective?

Rebuttal:

- The book cites numerous randomized controlled trials, from retirement savings to energy use, showing large behavioral impacts.

- When nudges backfire (as in overly aggressive tipping defaults), they can be adjusted.

- Like any policy, nudges must be tested, refined, and sometimes discarded.

“Our nudges are rooted in humility. If they don’t work, we try something else” (p. 195).

7. “Nudging Treats People as Irrational”

Finally, some argue that behavioral economics is paternalistic and elitist, implying that people cannot think for themselves.

Rebuttal:

- Thaler and Sunstein do not claim people are stupid. They are human.

- All humans—rich or poor, educated or not—are prone to systematic cognitive biases.

- Even experts use defaults, miss deadlines, and forget passwords.

“People are not dumb. But they are busy, and life is hard. Nudging helps them focus on what matters” (p. 197).

Affirming the Ethical Foundation

The authors end this chapter—and the book—with a reiteration of their ethical commitments:

- Transparency: Nudges must be public and accountable.

- Freedom of choice: No banning, no coercion.

- Welfare: The goal is to make people’s lives better as judged by themselves.

- Humility: Policies should be tested, measured, and revised as needed.

“Libertarian paternalism is not an oxymoron—it is a modest, evidence-based path between laissez-faire and regulation” (p. 200).

They argue that in a world where design is inevitable, intentional design—nudging people gently toward health, savings, sustainability, and generosity—is the most ethical way forward.

Final Reflections

Part V: The Complaints Department isn’t just defensive—it is clarifying, philosophical, and reflective. It acknowledges the tension between influence and freedom, but shows how the design of decisions can reconcile the two.

Key principles reaffirmed:

- Choice architecture is everywhere—it’s inescapable.

- Nudges respect autonomy; they are optional and transparent.

- Well-designed nudges lead to better decisions—individually and collectively.

- Libertarian paternalism seeks a middle path: one that uses science and ethics to improve lives without reducing freedom.

In sum, nudging is not about trickery or control. It is about designing systems that are aligned with human behavior and values, and that empower people to live the lives they want—without mandates, without shame, and without removing a single option.

As Thaler and Sunstein conclude:

“We all need a little nudge, now and then. Why not make those nudges smart, humane, and helpful?” (p. 202).

B. Libertarian Paternalism and Choice Architecture

Perhaps the most controversial yet practical idea of the book is Libertarian Paternalism, which suggests that:

“It is both possible and legitimate for private and public institutions to affect behavior while also respecting freedom of choice”.

This is not coercion. It’s not banning or mandating. It’s about nudging people towards better choices — better health, better finances, better lives.

C. Applications of Nudges

The book explores how subtle design tweaks can lead to significant behavioral improvements:

- Savings: The “Save More Tomorrow” plan encourages workers to commit future raises toward retirement savings. Result? Participation soared from 49% to 86%.

- Health: Positioning healthier food at eye-level nudges kids to eat better in school cafeterias.

- Organ Donation: A “mandated choice” system requires people to opt-in or opt-out explicitly, increasing donor rates.

- Education: Simplifying forms and reminders increases college application rates among low-income students.

D. Policy and Government Implications

The authors dissect programs like Medicare Part D, identifying poor choice architecture (e.g., random default assignments) as a major flaw. Better nudges could optimize outcomes without sacrificing autonomy.

Critical Analysis: Does Nudge Truly Deliver?

As I turned the pages of Nudge, I was struck not just by its ideas, but by its tone. This is not a dry economic textbook or a bureaucratic policy guide. It’s a humanist’s toolkit, designed to empower people—not control them. Yet, the concept of libertarian paternalism does invite scrutiny, even philosophical discomfort.

A. Evaluation of Content: A Powerful Framework with Measurable Impact

One cannot overstate the elegance of the central idea: you can influence behavior without eliminating freedom. Thaler and Sunstein’s behavioral interventions are not theoretical experiments—they have changed lives. According to their own data:

“Participation in 401(k) retirement plans increased from 49 percent to 86 percent within months when workers were automatically enrolled”.

The book’s use of empirical studies, from the Schiphol Airport urinal fly etching (which reduced spillage by 80%) to Medicare Part D analysis, supports its arguments with persuasive clarity.

However, the critics raise valid concerns. What if the nudger is misinformed? Who decides what’s “better” for the nudgee? Is it ever truly possible to be both libertarian and paternalistic?

B. Style and Accessibility: The Art of Making Economics Human

Perhaps what makes Nudge so digestible is its humane tone. Thaler’s voice (the dominant narrative persona by agreement) is humorous, unpretentious, and often self-deprecating. In the Preface, they admit:

“Thaler is famously lazy and Sunstein could have written an entirely new book in the time it would take to get the slow-fingered Thaler to agree to anything.”

The inclusion of fictional anecdotes like Carolyn, the cafeteria director, humanizes the abstract notion of “choice architecture.” These are relatable case studies, not cold hypotheticals. This narrative style makes the book especially accessible to general readers, students, and policymakers alike.

C. Thematic Relevance: Why It Matters in 2025

In an age where digital platforms algorithmically curate our reality, nudges have evolved from cafeteria layout decisions to tech interface manipulations. In this light, Nudge is more relevant now than ever. It anticipates modern dilemmas around data privacy, digital addiction, and climate behavior.

For instance, Chapter 8 introduces the concept of “sludge”—the bureaucratic cousin of nudge. It’s the deliberate addition of friction to slow or prevent action: think long cancellation forms, hidden unsubscribe buttons, and health insurance denial letters. They write:

“Every organization should create a seek-and-destroy mission for unnecessary sludge.”

This call to action is both timely and urgent.

D. Author’s Authority: Why We Trust Them

Thaler’s Nobel Prize and Sunstein’s policy credentials (serving in the Obama and Biden administrations) lend the book immense credibility. But what strengthens it even more is their transparency and intellectual humility. They openly address criticism, revisit old positions, and adjust views in The Final Edition.

They clarify one misunderstood policy stance emphatically:

“We do not support the policy called ‘presumed consent’ for organ donation.”

This candor and reflexivity are rare in economics literature—and refreshing.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths:

- Universal applicability: From school lunchrooms to corporate boardrooms, nudges are scalable.

- Data-rich storytelling: Every argument is accompanied by real-life case studies or compelling statistics.

- Interdisciplinary relevance: Touches on law, economics, psychology, health, and environmental science.

- Actionable and ethical: Policies are non-coercive, transparent, and preserve individual choice.

Weaknesses:

- Ambiguity of ‘better off’: The book repeatedly says nudges aim to make people “better off as judged by themselves,” but this is hard to quantify, especially in cases of addiction or mental health.

- Over-reliance on soft power: Critics like Elizabeth Kolbert have questioned if a nudge is enough. “If the nudge can’t be depended on to recognize his own best interests, why stop at a nudge?” she asks in The New Yorker.

- Neglect of cultural context: Most examples are Western-centric. There’s limited analysis of how nudges function across different societies with different value systems.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence

The book’s cultural reach has been nothing short of phenomenal. It was named one of the best books of 2008 by The Economist. The Guardian called it “a jolly economic romp but with serious lessons within”.

Yet not all reviews were glowing. British journalist Bryan Appleyard deemed it a “dogged march through social policies with boring lists,” suggesting that it needed “more elaboration of the central idea”.

Nonetheless, its influence is unassailable:

- It inspired the creation of the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, or “Nudge Unit”.

- It reshaped public health, especially regarding smoking, obesity, and COVID-19 response strategies.

- In the U.S., it has affected how retirement plans are structured and even how tax forms are pre-filled.

Gerd Gigerenzer criticized the overuse of the term “nudge,” arguing that “almost everything that affects behavior has been renamed a nudge,” thus diluting its meaning. This critique is a valid warning to keep the term precise.

Quotations: The Book’s Wisdom in Its Own Words

Below are some of the most insightful quotations from Nudge:

- > “A nudge…must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates.”

- > “There is no such thing as a ‘neutral’ design.”

- > “We are supposedly experts on biases in human decision making, but that definitely does not mean we are immune to them!”

- > “Defaults can have huge effects… participation rates can increase by 25 percent or more simply by changing from opt-in to opt-out.”

Overall impression

Thaler and Sunstein’s Nudge excels at fusing academic rigor with storytelling. It’s informative without being intimidating, accessible yet deeply profound. It has transformed how we think about:

- Public policy

- Personal finance

- Healthcare systems

- Digital platforms

- Corporate culture

Its influence spans from government agencies to UX design teams, and it has even sparked international behavioral units designed to improve policy outcomes without authoritarian mandates.

“Nudge helps us understand our weaknesses, and suggests savvy ways to counter them.” — The New York Observer

But no book is without flaws. Critics rightly point out the book’s occasional Western-centric bias and the fuzzy boundary between nudging and manipulation. Yet, even in its shortcomings, Nudge invites dialogue. And that might be its most powerful nudge of all — it doesn’t close a conversation, it opens one.

Recommendation: Who Should Read Nudge?

If you’re a policy maker, this book is required reading. If you’re a business leader or marketer, it offers invaluable insights into consumer behavior. Educators, health professionals, UX designers, and even skeptical philosophers will all find this book worth their time.

But perhaps most importantly, if you’re a human being navigating daily decisions, this book will help you understand yourself better. That, in itself, is a rare achievement in nonfiction.

✅ Verdict: A must-read masterpiece in behavioral science, Nudge is both an intellectual triumph and a practical guide for building a better world — one choice at a time.

Optional Comparison with Similar Works

To contextualize Nudge, let’s briefly compare it to a few other giants in the field of behavioral science.

| Book Title | Author(s) | Focus | How It Compares to Nudge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thinking, Fast and Slow | Daniel Kahneman | Dual-process thinking, biases | More academic; Nudge is more policy-focused |

| Predictably Irrational | Dan Ariely | Behavioral quirks and irrationality | More anecdotal; less structured policy advice |

| Misbehaving | Richard H. Thaler | History of behavioral economics | Deep dive into the discipline; less pragmatic |

| Influence | Robert B. Cialdini | Persuasion and compliance psychology | More about persuasion; Nudge is about design |

If Thinking, Fast and Slow is the theory, Nudge is the application. If Predictably Irrational is the entertainment, Nudge is the roadmap.

In a world drowning in decisions, Nudge is the lifeboat that lets us steer, rather than drift. It reminds us that small changes—nudges—can create massive shifts in behavior. And it challenges institutions to design systems that work for, not against, human nature.

As a reader, I walked away not just informed, but transformed.

“There is no such thing as neutral design. Every choice environment is a form of architecture. The question is: what will we build?” — Nudge

Let that be the nudge you take with you.

15 real-life applications and takeaways from the book Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein:

- Improving Public Health Choices: Cafeteria design can influence healthy eating habits. By placing healthier options at eye level and making unhealthy items less accessible, people are more likely to make nutritious food choices .

- Automatic Enrollment for Retirement Plans: Opting employees into retirement savings plans by default significantly increases participation rates. People often stick with default options, making it a powerful tool for promoting long-term financial security .

- Default Options in Insurance: In settings like health insurance, providing default options for plans can simplify decision-making and ensure more people opt into essential coverage .

- “Look Right” Signs for Pedestrian Safety: In places like London, where traffic flows differently than in other countries, the use of “Look Right” signs on pavements has effectively prevented pedestrian accidents caused by unfamiliar traffic patterns .

- Tax Returns and “One-Click” Filing: Simplifying processes like tax filing by sending pre-filled returns that can be filed with one click helps reduce bureaucracy and increases compliance .

- Designing Financial Choices: The concept of “smart disclosure” can be used to help consumers make better financial decisions. By making important information easily accessible, individuals are more likely to choose options that benefit them .

- Preventing Overconsumption with Default Restrictions: Setting default limits on purchases or consumption (e.g., limiting the amount of junk food in a basket) can guide people to make healthier choices without explicitly restricting them .

- Nudging for Green Energy: By providing default options for renewable energy plans, utilities can nudge customers towards environmentally-friendly choices, promoting sustainability without forcing them to make the decision .

- Promoting Social Good through Commitment Devices: People struggling with self-control can use commitment devices, like setting up automatic contributions to a savings account, which help them stick to long-term financial goals .

- Behavioral Insights in Public Policy: Governments around the world, including in the UK and the US, have adopted nudging strategies to improve public policies in areas like health, education, and environmental sustainability .

- Reducing Sludge in Bureaucracy: Streamlining forms and processes, such as automatically filling out tax returns or creating one-click filing systems, can reduce “sludge” and make decision-making easier for citizens .

- Taxation for Public Health: Implementing “sin taxes” on products like sugary drinks or cigarettes can nudge consumers towards healthier choices by raising the cost of unhealthy products .

- Using Social Norms for Behavior Change: Highlighting the behavior of the majority (e.g., “Most people recycle”) can encourage others to conform and make more environmentally-conscious decisions .

- Simplified Financial Planning: For complex decisions like choosing a mortgage or insurance plan, reducing complexity and presenting curated options can help consumers make better, more informed choices .

- Empowering Employees to Speak Up: In organizations, empowering lower-status members, like nurses, to speak up if a mistake is about to be made (e.g., missing a step in a medical procedure) can improve overall organizational performance .

These examples show how the principles from Nudge can be applied in both personal and societal contexts to improve decision-making and behavior, benefiting individuals and communities alike.

Conclusion: The Nudge That Changed the World

Reading Nudge feels like being gently guided through the psychology of your own decision-making flaws—only to find out that you are not alone, and better choices are well within reach. At its heart, Nudge is not about tricking people or manipulating outcomes. It’s about designing environments that empower people to act in their own best interests, even when their cognitive biases, emotions, or inertia get in the way.

The concept of libertarian paternalism—initially paradoxical—emerges as a rational, compassionate framework in a world filled with choice overload. It respects autonomy while recognizing human fallibility. And it’s this exact nuance that makes the book timeless.