Last updated on May 10th, 2025 at 09:42 am

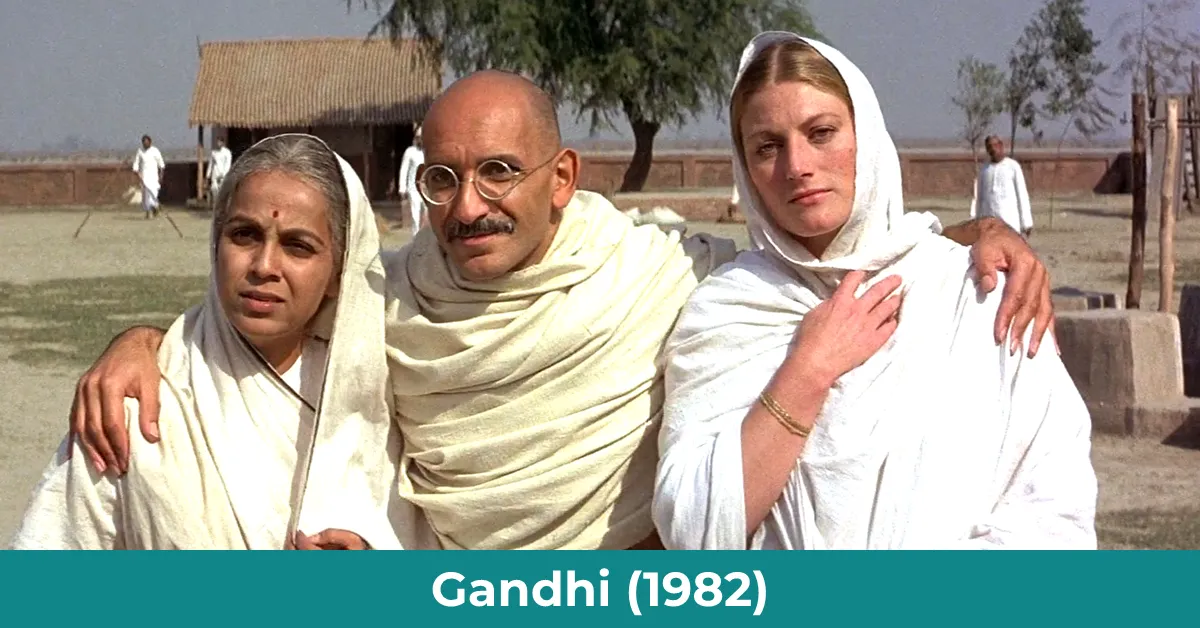

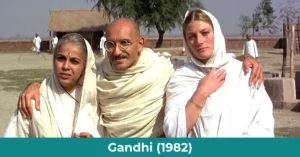

Gandhi 1982 is a British-Indian historical biopic drama film that tells the story of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, an Indian lawyer who became the leader of the Indian independence movement against British colonial rule.

The film marvellously portrays the life of Mahatma Gandhi who became India’s political hero and spiritual guru through his non-violent approach to achieving Swaraj or home rule from the British colonial hegemony. It also shows how Gandhi’s dream of a united independent India was shattered in the partition of India by creating Pakistan as an independent country for Muslims.

The film stars Ben Kingsley as Gandhi, with a supporting cast that includes Rohini Hattangadi as Kasturba Gandhi, John Gielgud as Viceroy Lord Irwin, Candice Bergen as Margaret Bourke-White, Edward Fox as Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, and Martin Sheen as Vince Walker.

The film was a critical and commercial success, winning eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor, Ben Kinsley. Directed by Richard Attenborough and written by John Briley, The British Film Institute Gandhi 1982 ranked it as the 34th greatest British film of the 20th century.

When I watched Gandhi 1982, I felt like I went back to my time. Felt like perhaps it was the exact ambience of the early 90s, so felt so attached to the atmosphere. Though the film showcases the bright side of Gandhi regardless of the pessimistic ideas of people like me, it shows the exact manner in which he rose to be Mahatma Gandhi. Having acquired half of the cost for the film from the Congress government, it duly pays its debts to the investors, Gandhi’s supporters and cinema lovers by recreating the history of India during its struggle for independence from the British Empire.

It represents Gandhi in his own real terms as if it were a documentary shoot in his lifetime with compelling reality. Every word Gandhi uttered was full of wisdom and uplifting for the spirit. But the dark sides and hypocrisy of Gandhi is a different subject matter discussed in The Doctor And The Saint by Indian eminent writer Arundhati Roy. It’s one of the 101 best films I have been reviewing.

Table of Contents

Storyline

On 30 January 1948, on his way to an evening prayer service, an elderly Gandhi is helped out for his evening walk to meet a large number of greeters and admirers. One visitor, Nathuram Godse, shoots him point-blank in the chest. His state funeral is shown, the procession attended by millions of people from all walks of life, with a radio reporter speaking eloquently about Gandhi’s world-changing life and works.

In June 1893, the 23-year-old Gandhi is thrown off a South African train in Pietermaritzburg for being an Indian sitting in a first-class compartment, despite his having a first-class ticket Realising the laws are biased even against well-educated and successful Indians, he then decides to start a non-violent protest campaign for the rights of all Indians in South Africa, comprised with indentured workers, arguing that they are British subjects and entitled to the same rights and privileges as whites.

After writing about the discrimination to the press, Gandhi with his wife gathered with other Indians in Natal under the banner of the South Africa Congress Party. Gandhi led the struggle of the passenger Indians bravely, and from the front. Two thousand people burned their passes in a public bonfire; Gandhi was assaulted mercilessly, arrested and imprisoned. To the gathered Indians, he said they were called to help in proclaiming the right to be treated as equal citizens of the empire.

To eliminate the difference between the Europeans and Indians, he proposes to burn the pass they had to carry around in fire in front of British security officials. The Congress Committee and its supporters drop their passes in a wooden bucket to be burned. Police obstructed the carrier, Khan, while bit Gandhi as he tried to collect the passes from the ground to put on the fire. There one day Gandhi met Charles Andrews, an English missionary who came from India to meet him.

After the march with the mine workers, Gandhi was imprisoned along with thousands of others. After a settlement with Jan Smut, Gandhi in 1915, after 21 years returned to India, in the royal navy ship with a heroic welcome by the Congress Party of India. Sardar Patel was with him.

Soon after that, he got himself involved in the ‘home rule struggle’ or Swaraj, inspired by his mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale, of the moderate faction of Hindus. He is urged to take up the fight for India’s independence (Swaraj or home rule, Quit India) from the British Empire.

He travelled the length and breadth of the country to get to know it. His first satyagraha or march was in Champaran, Bihar, in 1917. Three years before his arrival there, landless peasants living on the verge of famine, labouring on British-owned indigo plantations, had risen in revolt against a new regime of British taxes.

Gandhi travelled to Champaran and set up an ashram from where he backed their struggle. Gandhi stayed in Champaran for a year and then left. Though he was arrested from Chmaparan for not leaving the province at the command of the authority. But the case was dismissed and he was released.

At Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s residence, Gandhi met with Maulana Azad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Patel and others in a meeting. There he proposed a nationwide general day of prayer and fasting with the abstention of work of all men on 6 April against the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, popularly known as Rowlett Act 1919 which gave the government powers of detention without trial to cope with the threat of revolutionary violence.

The satyagraha had been planned to protest the Rowlett Act passed in 1919 to extend the British government’s wartime emergency powers. But the public unrest went out of control which created intense chaos which broke him badly.

All sections of Indian political opinion protested and Mohandas Gandhi launched his first all-India mass civil disobedience campaign to defy the new law. It led to some localized violence in Bombay and Delhi. The agitation and protestation led to the Amritsar Temple massacre.

At the order of General Dyer, 1516 protestors were killed including women and children on 13 April 1919, known as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre. The crowds at Amritsar had gathered to protest against the Rowlatt Bills and demonstrate nationalist sentiment.

Later as a part of the non-cooperation movement against British rule, on 31 August 1921, Gandhi ordered burning the of foreign clothes during his speech and the replacement of foreign apparel with the hand-spun fabric of Khadi.

In 1922, when the Non-Cooperation Movement was at its peak, things went out of control. A mob killed twenty-two policemen and burnt down a police station in Chauri Chaura in the United Provinces (today’s Uttar Pradesh). Gandhi saw this violence as a sign that people had not yet grown into true marchers, that they were not ready for non-violence and non-cooperation.

After the massacre, Gandhi declared the campaign to be stopped. He said he would fast indefinitely until the campaign stopped. Without consulting any other leaders, Gandhi unilaterally called off the march. But stopped it though, he was arrested again on sedition on 10 March 1922 and was sentenced to 6 years of imprisonment. After his release, he started his life his Porbandar Ashram in Gujarat, his birthplace.

Raising anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km Salt Satyagraha, or Dandi Salt March in 1930. He called on Indians to march to the sea and break the British salt tax laws. Hundreds of thousands of Indians rallied to his call on the anniversary of the Amritsar Massacre towards the Indian Ocean.

He was arrested and Gandhi was imprisoned again and ninety thousand people were arrested were also arrested. However, Gandhi was released in 1931, halting the campaign after the British made concessions to his demands.

In the same year, Gandhi represented the Indian National Congress at a round table conference in London to discuss India’s possible independence, called by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. He did not like the British idea of dividing India on religious lines.

In 1942, during the Quit India Movement, Gandhi was arrested along with his wife and was imprisoned in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune where his wife dies of a heart attack.

By 1944 the British government had agreed to independence, on the condition that the Congress Party and the Muslim League resolve their differences. Despite Gandhi’s resistance to the principle of partition, India and Pakistan became separate states when the British granted India its independence in 1947. Bloody sectarian violence ensued. on 23 March 1947, the last viceroy Mountbatten came to India and oversaw the Partition of India into India and Pakistan.

Jinnah wanted India bifurcated with Muslim-majority provinces to Pakistan for he feared that after the end of the British slavery, Hindus will enslave Muslims in a Hindu-majority India despite Gandhi’s assurance of their protection. Gandhi was obstructed by a group of Hindu nationalist protesters outside his ashram. One of them told him not to meet with Jinnah.

In the meeting, when Gandhi proposed Jinnah to be the first prime minister of India instead of breaking India by letting Nehru stand down, Nehru replied that the majority Hindus fear that he is giving too much to the Muslims and no one would accept it while Jinnah threatened Gandhi with the possible war in a united India.

Fearing the civil war, Gandhi gave in to an independent India and an independent Pakistan. India had been divided. At his ashram in Calcutta, the flagstone was seen without a flag. He did not celebrate the independence of a divided India which began bloody Hindu-Muslim riots, especially in Muslim-majority West Bengal.

Religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims erupted into nationwide violence. Repulsed by this sudden unrest, Gandhi declared a hunger strike, in which he will not eat until the fighting stopped. The fighting does stop eventually.

Riots ensued during the Hindu-Muslim migration from and to India and Pakistan. According to Kuldip Nayar’s account, the number of people killed in migration is 1-3 million as 10 to 12 million non-Muslims from Pakistan and Muslims from India migrated.

As the British rule ends, Gandhi travelled to Calcutta amid the fierce prostration and riot appealing for peace and staying in a Muslim house. He began to fast until normalcy prevailed in Calcutta. He fell seriously ill there during the time when came Hossein Shahid Shohrawardy, the inciter of the great Calcutta killing, to ensure that the riot had stopped.

At times, as a Hindu rioter came to complain to Gandhi that he is going to hell because he killed a Muslim child to avenge his dead son who was killed by Muslims, he suggested that he must find an orphan boy and raise him as a Muslim as penance. Gandhi spends his last days trying to bring about peace between both nations.

Back in New Delhi in Birla House, Mathuram Godse shot him in the chest on his way to his evening prayer, on 30 January 1948. Gandhi is cremated and his ashes are scattered on the Ganges.

What to Consider

The Gandhi 1982 is a portrayal of Mahatma Gandhi’s life and his works related to political change during India’s struggle against British oppression in a nutshell. His rise in politics and the development of political philosophy is somewhat captured. Time indeed created a Mahatma, ‘great soul’ when it was needed most when fortune made him a great leader of him.

As it just happens that all great men bore great critiques, so did Gandhi in the same land for all he willed to dedicate his life, accepted asceticism, and hoped to be the reincarnation of Jesus Christ whom he covertly envied and quoted in numerous incidences.

When the angry mob attacked the police station and killed police and his non-violence approach failed, some of his leaders thought it was just an eye for an eye against the British oppression, Gandhi retrospectively said, “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind”, echoing Jesus Christ, “You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. But I tell you not to retaliate the injury; but whoever strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other to him also”.

An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind

Mahatam Gandhi

From the later part, I think, born his non-violence approach of which he narrates the meaning as, “I suspect he meant you must show courage be willing to take a blow, several blows, to show you won’t strike back, nor will you be turned aside. And when you do that, it calls on something in human nature that makes his hatred for you decrease and his respect increase.”

When visited by Charles Andrews, the Anglican priest, he said about the deplorable condition of attire, “If l want to be one with them l have to live like them”, which matches with Saint Paul’s “To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews.”

When Gandhi said, “They will imprison us. They will fine us. They will seize our possessions. But they cannot take away our self-respect if we do not give it to them”, it has a similarity to what Jesus Christ says, “And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell.”

True that his humanistic philosophy developed from Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Islam, Leo Tolstoy’s thinking on Christianity and Hinduism. Though, Arundhati Roy writes, “Born into a Bania (Vaishya) family in 1869—Gandhi was one of the Hindu reformers after Ishwar Chandra Bidya Shagor and Raja Rammohan Roy. For his entire life, the Bhagavad Gita was his guiding text in his spiritual, moral and political trajectory.

Even though throughout his entire political career he tried to empathise with Muslims and assimilate every religion into one common political platform, he sustained very regressive, lopsided, anti-modern, anti-liberal views about the Untouchables, Dalits, Bhangis (Scavengers) and lowly castes who have been embroiled with swirling servitude, subjected of inhuman treatment, barred from the right to live like human beings; and have been fighting for equality, social acceptance, spiritual recognition, and financial well-being.”

Nevertheless, Gandhi somehow caught the tide. Born as a prince into a well-to-do family he was privileged to join the Inner Temple, one of the four London law colleges, whose father was the prime minister of the princely state of Porbandar.

He accepted voluntary poverty and remained in that state till his death, remained half naked in self-spined khadi clothes to show how determined to reject the European clothes made in European industries depriving the local indigo industry. Gandhi was John Maxwell’s type of leader who “knows the way”, he said, “shows the way and goes the way”.

Yet, there are numerous things that shed light on Gandhi. Let us take suppose when he said to New York Times journalist Vince Walker when asked why in his ashram he prepares the meal and cleans toilets, he said “Yes, it’s one way to learn that each man’s labour is as important as another’s. While you’re doing it, cleaning the toilet seems far more important than the law.” He even tried to throw his wife out of the ashram as she refused to do the works of untouchables, in South Africa.

He once confided to Ms Slade, who he called Mirabehn and who became a lifelong devotee to Gandhi, that “When I despair, l remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and, for a time, they can seem invincible. But in the end, they always fall.”

One sentence that struck me hard is “Where there’s injustice, I always believed in fighting. The question is, do you fight to change things or to punish?” He clarified to Nehru and other his kind of fighting which is to change the minds of the ruler not to punish them which separate the base intention of revenge from Christ’s kind of fight against all form of evil and injustice by making them see the wrong. Gandhi meant, to fight to change the perception, not to avenge which is up to God. “I will fight for freedom, but I will not hate”, he said.

I will fight for freedom, but I will not hate”

Mahatma Gandhi

He really believed that non-violence can change the world for the better, even if that non-violent approach is directed against a cruel ruler like Adolf Hitler. When house-arrested in Aga Khan Palace, Life magazine photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White asked him, “Do you really believe you could use nonviolence against Hitler?

“Not without defeats” Gandhi replied, “and great pain. But are there no defeats in this war? No pain? What you cannot do is accept injustice from Hitler or anyone. You must make the injustice visible. Be prepared to die like a soldier to do so”. When asked about his determination to visit Pakistan, to Margaret Bourke-White he responded by saying, “I’m simply going to prove to Hindus here and Muslims there that the only devils in the world are those running around in our own hearts. And that is where all our battles ought to be fought.”

Despite any controversies and criticism, I must put what the English commentator said during Gandhi’s funeral, “A private man with no wealth, no official title or office nor the commander of armies or a ruler of vast lands. He could not boast any scientific achievement or artistic gift.

Yet men governments, dignitaries from the world over have joined hands today to pay homage to this little brown man in the loincloth who led his country to independence. Mahatma Gandhi has become the spokesman for the conscience of all mankind. He was a man who made humility and simple truth more powerful than empires.”

Just before the final talk with Jinnah on Pakistan’s independence Nehru and Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad came to take to Jinnah’s place. He was in his ashram when he abruptly stood up without the help of his living sticks, Manu and Aba who hurriedly joined him to assist. Seeing their promptness he said, I’m your granduncle but l can still walk either of you into the ground. I don’t need to be pampered in this way.”

Then he placed a light slap on Manu or Aba’s nodding head on his right side, the suddenly changed his mind and tapped tenderly on her head”, the scene and flawlessness of which made me enthralled.

Gandhi 1982: Analysis

Gandhi 1982 is a film that deals with themes of freedom, justice, and nonviolence. It shows how Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence was able to unite the Indian people and bring about change. The film also highlights the importance of leadership, and how one person can make a difference. Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence is still relevant today and is a powerful message for all people facing oppression.

Whatever your expectations are of Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, they are likely to be exceeded. Expectations of a $22m enterprise, half of which were obtained from the Indian Government. The film does not betray anything of Attenborough’s 20-year struggle for the means to make it.

Attenborough might well have been prevented at that time if he had known that before the project would be granted, he would be 20 years older; that his three most valued supporters—Nehru, Lord Mountbatten and an Indian Civil Servant named Mothilal Kotari, to whom the film is jointly dedicated– would all have died.

The striking virtue of the film is its uncompromising simplicity. Gandhi’s life, purpose and influence are evoked through a series of sketches of incidents and people, covering the five and a half decades, from his arrival in South Africa to his death by assassination in 1948, soon after the independence of India for which he had fought throughout his life and the partition of the country which had devastated his hopes.

Such simplicity demands expertise as well as discipline. Gandhi is a model of old, conservative, and in this case admirable virtues of the British cinema, in technical method and performance. Almost entirely shot in India, in hard climates and locations, the film is technically immaculate.

The photography of Billy Williams and Ronnie Taylor never succumbed to the almost irresistible temptations of the picturesque, while sensuously conveying the sense of light and dust-haze. The remarkable technical expertise that accomplishes the ageing process of the principal characters covering half a century is wholly modest, especially of Gandhi, played by Ben Kingsley.

In a revealing interview with an enterprising new film magazine Stills, Attenborough notes that the resourcefulness of Kingsley’s stage training equipped him to deal with the unpredictability of working with huge crowds of extras when it is estimated that around a million Indians appear in the film. Kingsley’s Gandhi is a wholly real and believable person, from the cheerful little lawyer of the nineties to the aged spiritual leader of a nation.

However, Gandhi is a major contribution to a year of thrilling success for British films. Much more important, it is an artist’s personal tribute, deeply felt and simply expressed, to the spiritual worth of another human being. “Gandhi showed us” Attenborough has said, “how to stop killing one another”.

Every act and scene was full of spontaneity, fascination and realism. But I kind of happen to find the rule of Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad (played by Birendra Razdan) raw, misplaced and amateurish.

Conclusion

Gandhi 1982 is a film that, I think, is definitely capable of quenching the thirst for the history of the Indian subcontinent and the British empire, and about a man who accepted voluntary poverty to speak for the oppressed and the subjects of injustice. The film stands the test of time as a powerful and emotionally resonant drama. Its portrayal of Gandhi and his philosophy of nonviolence is a masterful one, and Ben Kingsley’s performance is widely considered to be one of the greatest in the history of cinema.

Gandhi’s portrayal of the Indian independence movement is also noteworthy, as it shows how Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence was able to unite the Indian people for good and bad and bring about political change.

The film’s depiction of the partition of India and Pakistan is also powerful and gives insight into the tragic aftermath of the independence movement. It is a film that not only offers an accurate account of the life of Mahatma Gandhi but also a powerful message of hope, unity, and nonviolence.

Gandhi 1982

10