Last updated on May 13th, 2025 at 03:26 pm

Hollywood’s 1982 blockbuster biopic ‘Gandhi’, directed by Richard Attenborough is a celebrated biography of Mahatma Gandhi.

The biopic that portrays Mahatma Gandhi as a nonviolent man won 8 Oscars in various categories. Gandhi’s valiant but nonviolent works regarding India’s sovereignty from the British colonial hegemony earned him the status of a saint and the reverence of a god.

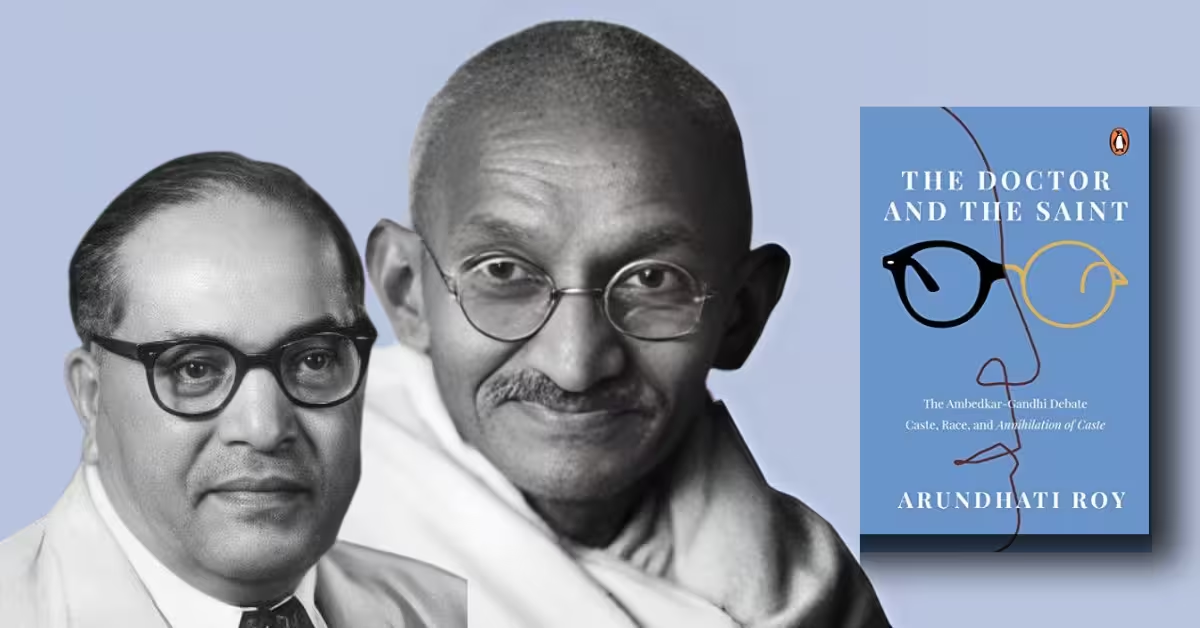

Like any other piece of work directed towards his greatness and stance for India’s freedom struggle, author Arundhati Roy sees it through a different angle in her work The Doctor and the Saint.

Attempting to be equated with oppressed Gandhi’s ‘Voluntary Poverty’ and ‘Satyagraha’ against the Empire-back injustice bemused the people from all walks. Regardless of political adversity, BJP loves him, the right nationalists love him as much as the left. Accordingly, people, like me, who have been believers of Gandhi around the world hardly ever dared ask the question: Why Gandhi happens to be who he is today?

The Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy’s book The Doctor and the Saint unfolds many such queries with answers. Presumably, Mahatma Gandhi is regarded as ‘the Saint’ while the father of the Indian Constitution Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar ‘the Doctor’.

The book with its invaluable research information from numerous reliable sources disseminates Gandhi’s unknown, untold and unpopular sites.

His rise, struggle for his political stance, political shrewdness, moral hypocrisy, his disregard and disdain toward social equality of Untouchables, and poor, and his outdated stoic philosophy are contained in the book. It outlines a socio-political debate set by Dr B. R. Ambedkar’s treatise The Annihilation of Castes against Mahatma Gandhi’s views about the caste system of Hinduism.

The following excerpts are taken from the book and have been aligned with my own thoughts and learnt facts about Gandhi, the contemporary political, social and liberal views.

Table of Contents

Background of The Doctor and the Saint

Arundhati Roy’s The Doctor and the Saint is not merely an introduction to B.R. Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste—it is a political and moral intervention. Originally published in 2014 as a preface to the annotated edition of Annihilation of Caste by Navayana, and later reissued by Haymarket Books in 2017, Roy’s essay juxtaposes the ideologies of two towering figures in modern Indian history: Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (the “Doctor”) and Mahatma Gandhi (the “Saint”).

The book traverses caste, class, religion, and nationalism in India, but its core aim is to deconstruct the glorified mythology surrounding Gandhi, especially in the West, and to illuminate the radical clarity and moral courage of Ambedkar. Roy pulls no punches in exposing how Gandhi’s belief in the caste system—albeit with reform—stood in direct contrast to Ambedkar’s call for its total annihilation.

Roy’s personal background as a Syrian Christian from Kerala informs her powerful observations. Her narrative interweaves autobiography, historical analysis, and scathing social critique, anchored by the devastating legacy of caste violence—from the chilling account of the Khairlanji massacre to the silent, everyday indignities suffered by Dalits across the country.

Her method is to reclaim Ambedkar’s revolutionary spirit from marginalization and institutional neglect, portraying him not only as the “Father of the Indian Constitution,” but as a radical thinker whose ideas remain dangerously relevant. Roy’s historical excavation is informed not only by Ambedkar and Gandhi’s writings but also by socio-political statistics, exposing how caste endures in contemporary Indian capitalism, media, politics, and religious discourse.

The Caste Burden

Casteism has time and again reignited the fire of racial atrocity against the ‘lower’, ‘impure’, ‘untouchable’, Dalit’ and aborigines tribes from the time of ancient in Indian culture.

Apart from the primary ‘four privileged-castes’ the rest are considered subhuman.

The author describes, “According to the National Crime Records Bureau, a crime is committed against a Dalit by a non-Dalit every sixteen minutes; every day, more than four Untouchable women are raped by Touchable; every week, thirteen Dalits are murdered and six Dalits are kidnapped. In 2012 alone, 1574 Dalit women were raped (only 10% ever reported), and 651 Dalits were murdered.

Dalits are stripped and paraded naked and forced to eat human waste.

Privileged castes punish Dalits by forcing them to eat human excreta which mostly goes unreported, seizing of lands, social boycotts, and restriction of access to drinking water. These wouldn’t include a Mazhabi Dalit Sikh who in 2005 had both his arms and leg cleaved off for daring to file a case against the men who gang-raped his daughter. Moreover, there is no separate statistic for triple amputees”.

The question ‘What is the use of the fundamental rights to the Negro in America, to Jews in Germany and to the Untouchables in India?’ keep resurfacing regarding ‘Untouchables’, ‘Scheduled Castes’, ‘Backward Class’, and ‘Other Backward Class’.

Even though some tend to compare ‘Casteism’ with ‘Racism’, either form of discrimination target people because of their descent. Accordingly, the author duly notes, “Other contemporary abomination like ‘apartheid’, racism, sexism, economic imperialism and religious fundamentalism has been politically and intellectually challenged at the international level forum.

How is it that the practice of caste in India—one of the most brutal modes of hierarchical social organisation that human society has ever known—has managed to escape similar scrutiny and censure? Perhaps because it has come to fuse with Hinduism and by extension with so much that is seen to be kind and good— mysticism, Spiritualism, non-violence, tolerance, and vegetarianism, the Beatles— that at least to outsiders that it seems impossible to fray, it loses and try to understand it”.

The origin of caste always mesmerises and tends to resurface debate for ages. But today’s caste system is known to be originated from Hinduism’s funding text Manusmiriti or the Law of Manu, during 1500 BC. Here Manu describes Vanrashramadharma

or Chaturvarna or the chief four castes of Hinduism. With approximately four thousand endogamous castes and sub-caste.

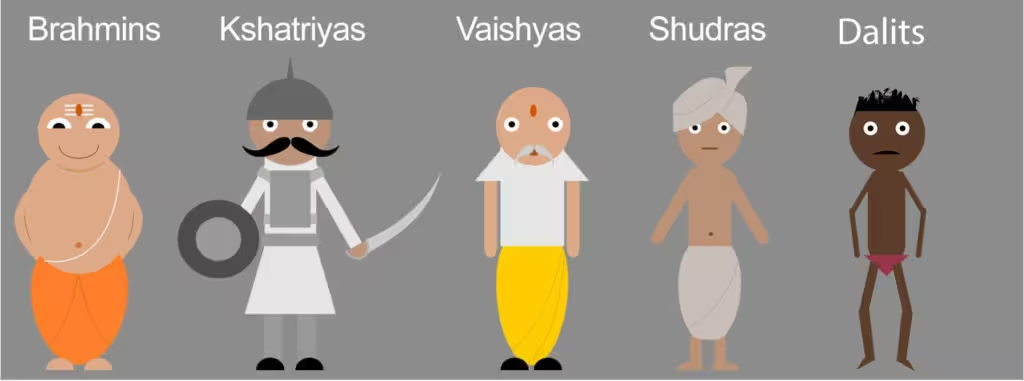

In Hindu social forms, the primary four castes are Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (soldiers), Vaishyas (traders) and Shudras (servants). Apart from the four primary castes, there are also the ‘avarna castes’, ‘anti-Shudras’, ‘Sub-humans’, the ‘Untouchables’, ‘the Unseenables’, ‘the Unapproachables’—whose presence, touch, the very shadow are considered to be polluting by the privileged-castes.

These people are forced to live in segregated areas. The Untouchables are not allowed to use public roads, drink from common wells, enter Hindu temples, share privileged-castes’ schools, cover upper bodies, and are forced to use a certain kind of clothes and jewellery.

It is a system of, “Ascending scale of reverence and descending scale of contempt”. Every scale with its prejudice ascends higher, ‘increases honour while every scale descends increases contempt’ where inter-castes ‘love is polluting, but rape by the privileged-caste is pure’.

In the caste-class system, every class is endowed with special privileges. Every class is interested in maintaining the levels in the system.

The “infection of imitation” of Brahmanism by the castes seen everywhere. “It is not that Brahmans are the ones to dominate the system. It is a domino effect of domination of every caste towards other castes downward. Brahmins against Kshatriyas; Kshatriyas against Vaishyas; Vaishyas against Shudras; Shudras against the Untouchables; the Untouchables against the Unseenables. There is Brahmanism everywhere it is like an elaborated network in which everyone polices everyone else by the virtue of caste hierarchy.

Unable to bear the social stigma on subordinate and other degraded lower castes by the privilege-castes millions converted to other religions like Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism and Christianity centuries ago, and still, do. Ambedkar himself with half a million of his followers converted to Buddhism in 1936.

By now India has had two Dalit presidents—Kocheril Raman Narayanan (1997-2002) and Ram Nath Kovind (acting)—a Dalit chief justice and Dalit political party: Bahujan Samaj Party (BSJ). In spite of numerous changes, caste-considered privileges are still in effect in India. The non-Congress the Bahujan Samaj Party led by Mayawati was the third largest political party by vote share in the 2014 Indian National Election, though it did not win any seats in the Lok Sabha.

But in the 2019 Lok Shaba Election, it shone brightly winning 10 seats from contested 348 candidates. It was formed to represent Bahujans (which literally means “people in the majority”), referring to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Castes (OBC), along with religious minorities.

But still, how injustice towards minorities and lowly castes, the privileged castes’ supremacy, and caste-based cronyism dominate India’s political, social, financial and religious landscapes are astounding.

The Brahmin Power

To comprehend just how the subordinate castes are socially and financially suppressed and forced to live inhumane lives in the swirling servitude, we must first realise how the privileged castes like Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas kept the rest of the population held up by virtue of merit and accumulating wealth.

Of the 1.2 billion-plus populace, “Not more than 3.6 per cent of Brahmin, today hold as much as 70 per cent of public jobs. Of 500, 310 are Brahmins in the positions like from deputy secretary to upward; of the 26 state chief secretory 19 are Brahmins; of the 27 Governors

and Lt. Governors, 13 are Brahmins; of the 16 Supreme Court judges 9 are Brahmins; of the 330 judges of High Court 166 are Brahmins; of the 144 ambassadors, 56 are Brahmins; of the 3300 IAS officers, 2376 are Brahmins; 40 per cent of Lok Shaba members are Brahmins”, and 84 per cent Brahmins above the age of 18 is literate.

The scenario simply proves that the tiny fraction of Brahmins holds between 35 to 65 per cent of all plum jobs available in the country.

The prosperity picture of Vaishyas which includes Banias, is even more overwhelming. “Of the 315 key decision-makers surveyed from 37 Delhi-based Hindi and English publications and television, almost 90 per cent English-language print media and 79 per cent in television were found to be ‘Upper Caste’, where 40 per cent belong to Brahmins”.

One of the four most important English national dailies The Hindu is owned by a Brahmin family concern. According to the Backward Classes’ Commission report, in 2007, 37 per cent of Indian Bureaucracy was made up of Brahmins.

It does not matter how small they are in number compared to the large population of India. The Brahmins still control the important sectors, get privileged considerations and have a dominant meritocracy in the country.

Vaishyas-The Traders

“In the recently published list of dollar-billionaires by Forbes magazine, 55 of them are Indians.

7 of the 10 from the 55 are Vaishyas—all of whom are CEOs of major corporations with business interests all over the world. They are Mukesh Ambani (Reliance Industries Ltd), Lakshmi Mittal (Arcelor Mittal), Dilip Shangvi (Sun Pharmaceuticals), the Ruia brothers (Ruia Group), K.M. Birla (Aditya Birla Group), Savitri Devi Jindal (O.P. Jindal Group), Gautam Adani (Adani Group) and Sunil Mittal (Bharti Airtel). Apart from business, Vaishyas (Banias) continue to firm hold on small trades in cities and on the traditional rural moneylending across the country, which has millions of impoverished peasants and Adivasis, including those, live in deep in the forest of India”.

Vaishyas accounted for 2.7 per cent of the population, and still, their economic clout in the Indian economy is extraordinary.

Of the four most influential English dailies 3 are owned by Vaishyas. The largest mass media company in India, whose holding includes The Times of India and its 24-hour news channel Times Now is owned by Vaishyas. The Hindustan Time and Indian Express are as well owned by Marwari Vaishyas. The most circulated Hindi daily, which has 55 million readers, Dainik Jagran is owned by a Vaishya from Kanpur.

The Dalit/Untouchables

But how about the Untouchables? “The total share of the Untouchables of the population is 12.5 per cent.

71.3 per cent of Scheduled Caste students drop out before they matriculate, the situation makes it even harder for them to avail even low-end public jobs. Only 2.24 per cent of the Dalit population is graduated. There are hardly any judges from Dalit or Adivasis in Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Karla”.

Dalit and Adivasi make up the majority, of whom millions are affected, and displaced, by mines, dams and other major infrastructure projects. Many of those who are designated as sweepers—who clean streets, who go down manholes and service sewage systems, clean toilets and do menial jobs—are Dalits.

“Caretakers’ jobs in malls and in corporate offices with swanky toilets that do not involve ‘manual scavenging’ go to non-Dalit, mostly women who continue to earn living by carrying baskets of human wastes on their heads as they clean traditional-style toilets that use no water”.

“India’s 13,400 trains transport 25 million passengers across 65,000 kilometres daily. Their excreta is funnelled straight onto the rail tracks through 72,000 open-discharge toilets.

This waste which is likely to amount to several tonnes a day is cleaned by hands, without gloves or any protective equipment, exclusively by Dalits”.

Moreover, to add fuel to their woes, the Untouchables, who dare to defy the system of caste could face a social boycott by orthodox privileged Hindus. They prevent the Untouchables from buying a piece of land, wearing nice clothes, smoking a bidi, riding a horse in a wedding procession or using shoes in the presence of a caste Hindu. The crime of an Untouchable can be ranging from an attitude to a posture that is less fearful toward the caste Hindus than expected.

“It is a non-cooperation by the powerful against the powerless”, that continues to prevail in the Hindu nationalist majority even these days.

What Did Gandhi Say About Caste-system?

Born into a Bania (Vaishya) family in 1869—Gandhi was one of the Hindu reformers after Ishwar Chandra Bidya Shagor and Raja Rammohan Roy.

For his entire life, the Bhagavad Gita was his guiding text in his spiritual, moral and political trajectory.

Even though throughout his entire political career he tried to empathise with Muslims and assimilate every religion into one common political platform, he sustained a very regressive, lopsided, anti-modern, anti-liberal views about the Untouchables, Dalits, Bhangis (Scavengers) and lowly castes who have been embroiled with swirling servitude, subjected of inhuman treatment, barred from the right to live like human beings; and have been fighting for equality, social acceptance, spiritual recognition, and financial well-being.

Gandhi who, “Became all things to all”, is a great broker of the caste system and not who we all think who he is for the powerless. He, after all, is not a saint that the East, the West, and Europe take for granted.

Gandhi, who was very much familiar with Jesus Christ, knew very well that a self-induced Christ-like lifestyle would earn him a position like Christ. Even though Gandhi’s ‘Voluntary Poverty’ can never be equated with Jesus Christ’s impoverished lifestyle, Gandhi chose to do so in his multiple communes in South Africa and India.

The journey to his sainthood began in the communes with young girls and boys around, with vast farmland full of fruit trees, servants to serve, goats for milk, and money followed in from his wealthy industrialist patrons. Whereas Jesus Christ had to fight for a square meal daily. Being struck by poverty and antipathy towards mundane worldly pleasure and his stand for the weak, the powerless, the impure, untouchables, depressed, lowly, ill, oppressed, unloved, and corrupt and the illegitimates make Jesus Christ the greatest human being in human history.

“Gandhi’s life and his writing which contains 48,000 pages are divided into ninety-eight volumes.

He never anywhere in his works he categorically renounced his belief in Chatur Varna or the system of four castes”. The matter of the fact is, that Gandhi said everything with its contradictions. His works and spoken words have been carefully cherry-picked, even by event, word by word and passage by passage, sentence by sentence by his followers which had made him a ‘wonder man’.

Jesus said, “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also”. Gandhi refashioned it and said, “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind”.

After returning from South Africa as a British subject in 1915, Gandhi remarked on the Caste system: “The vast organisation of caste answered not only the religious wants, but it answered too its political needs”…. “I believe Hindu society has been able to stand, it is because it is founded on caste-system”.

Gandhi, the promoter of the idea of Ram Rajya Utopia, no matter how contradictory or baffling to the anti-caste protagonist he, in 1921, said, “Caste is another form of control. Caste puts limits on enjoyment. Caste does not allow a person to transgress its limits in pursuit of enjoyment. That is the meaning of such caste restrictions as inter-dining and intermarriage …..These being my views I am opposed to all those who are out to destroy the caste system”.

Ambedkar, who had been advocating for the rights and separate electorate for the Untouchables, Dalits and subordinate castes encountered Gandhi in 1931 at the Second Round Table Conference in London. After a heated debate that lasted for weeks, Gandhi eventually agreed to separate the electorate. Not to the Untouchables but for Muslims, and Sikhs.

He did not agree with Ambedkar’s demand for a separate electorate to the Untouchables.

Because Gandhi refused to believe that Ambedkar, who himself was hailed from the Untouchables, had no right to represent the Untouchables. He rather replied saying, “Those who speak of the political rights of the Untouchables do not know their India, do not know how Indian society constructed, and therefore, I want to say with all the emphasis that I can command that it, I was the only person to resist this thing I would resist it with my life”.

“In 1832, when Gandhi was serving jail terms in Poona for breaking the Salt Tax law, Ramsey MacDonald declared the British government’s decision on the Communal Question. It awarded the Untouchables a separate electorate for a period of twenty years”.

“Hearing that Gandhi took to a pure blackmailing demand and said that unless the provision of a separate electorate for the Untouchables was revoked he would fast to death”. A hunger strike against the rights of the Untouchables!

Contradicting his non-violent maxim of Satyagraha, after waiting for one month he began his fasting from prison. As the tension started mounting Ambedkar and other Untouchables leaders feared that they would be blamed by the whole Hindu community if Gandhi succumbed to death from fasting. Seeing no way around 1932, September 24, Ambedkar visited Gandhi in prison and signed the ‘Poona Pact’.

Being a powerful voice against ‘indentured labourers’ in South Africa and social injustice against the Untouchables in India, did Gandhi really ally himself with the poorest of the poor?

During his visit to the Balmiki Colony in 1946 in Delhi, he refused to eat with the poor people. When he was offered food he said, “You can offer me goat’s milk, but I will pay for it. If you are keen that I should take food prepared by you, you can come here and cook for me”. He fed nuts, offered by Dalits, to his goats saying he would eat them later in the goat’s milk.

Gandhi’s power cravings and political hypocrisy were observed during the time when he rallying to strengthen his political career. In an attempt to win over the three primary constituencies –the privileged-caste Hindus, the Untouchables and the Muslims—to the Indian National Congress party, Gandhi showcased his political shrewdness subtly.

Firstly, “To the conservative privileged-Caste-Hindus, he held political tactics of Utopian Ram Rajya and Bhagavad Gita as his Spiritual dictionary. “He called himself a Sanatana Hindu, who positioned himself as the origin of all things, the container of everything. Politically the idea is used for the narrow purpose of assimilation and domination where all religions- Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism and Christianity- are sought to be absorbed”.

Secondly, “To his second constituency, the Untouchables, Gandhi, the Congress under his leadership, passed a resolution in 1917 abolishing ‘untouchability’. Here too he suggested segregation of Untouchable children from the ‘purer’ caste children”.

Thirdly, “The constituency that the Congress needed was that of the Muslims. To win it over, in 1920 the Congress decided to ally with conservative Indian Muslims who were at the time at agitation against the ‘partition of Ottoman Empire’. The Sunni Muslims who

took the ‘partition of the Ottoman Empire’ as equal to a ‘threat’ to Islam’s Caliphate, were looking for a refuge to restore it. Led by Mahatma Gandhi, the Congress leapt into the fray and included the Caliphate in the party’s national Satyagraha.

It was during the first Non-cooperation Movement that Gandhi, instead of creating an atmosphere to assimilate everyone, regardless of caste, race and religious consideration, made Hinduism the central tenet of his political career.

Financially supported by G.D Birla, who owned the Hindustan Times, Gandhi always wanted to live like the ‘poorest of the poor’. “Though he spoke of inequality and against poverty, to these he sometimes sounded like a socialist. At no point in his political career, he ever confronted the Industrialists or the landed aristocracy. He always sided with the Indian landlord and against peasants”.

In South Africa, he chose to fight and stand for his ‘wealthy Muslim merchant friends and rich ‘Indian Passengers’, instead of for the indentured labours who were under severe servitude in the farms owned by White Africans during the Pass Law agitation.

Because of Gandhi’s ignoble and filthy act, instead of gaining a separate electorate, the Untouchables would have reserved seats in general constituencies.

“Among the (many) reasons why criticism toward Gandhi is not just frowned upon but often censured in India is because Hindu nationalists will seize upon such criticism and turn it to their advantage. The fact is there was never much daylight between Gandhi’s view on caste and those of the Hindu rights”, says Arundhati Roy.

Gandhi’s Rise to ‘Mahatmahood’

A man who had become a ‘great soul’, the centre of eyes for many, inspires many to dream a political dream, have been idealised by millions had indeed a dramatic and hysterical beginning. His political profile had started taking form in South Africa. “Mahatmahood’ provided Gandhi with an amplitude that is not available to ordinary mortals”.

How did Gandhi come to be called ‘Mahatma’? Did he begin with the compassion and egalitarian instincts of a saint? Historian Ramchandra Guha said, ‘His canonisation of Mahatmahood began in 1915, soon after his return from South Africa as he started working in India in the town of Gondal, Porbandar in Gujarat”.

About his garnering the ground of Mahatmahood, Ramchandra Guha also said, “In 1915, Mohandas K. Gandhi came back to India after two decades in the diaspora.

Living in South Africa, he had been seized of the need to build harmonious, mutually beneficial, relations between Hindus and Muslims. This commitment to religious pluralism he now renewed and reaffirmed. Meanwhile, he progressively became more critical of caste discrimination. To begin with, he attacked ‘untouchability’ while upholding the ancient ideal of varnashramadharma. Then he began advocating inter-mixing and inter dining, and eventually, inter-marriage itself”.

Already married, the 24-year-old Gandhi, after being trained as a lawyer in London’s Inner Temple, landed in South Africa in 1893. His first job was of a legal adviser under a wealthy Muslim merchant from Gujarat. However, he suddenly got himself into a political awakening right after a few months of his arrival.

Racism in South Africa at the time was at its peak. Discrimination against Black Native Africans by the Whites was severe. One day, Gandhi was thrown out of a ‘White Only’ first-class coach of a train in Pietermaritzburg, being a victim of the prevailing racial discrimination.

Gandhi saw how the ‘Passenger Indians’, who were predominantly Muslims and privileged-caste Hindus, were being subjected to discrimination. Owing to skin-colour, the Indians were too being treated as Native Black Africans by Whites.

Eventually, Gandhi voiced against this unequal treatment of the British imperial subjects in South Africa.

Soon after his arrival, Gandhi became Secretary of the Natal Indian Congress, in the Natal province of South Africa. The very first political involvement and the victory of the Natal Indian Congress came in 1895. The ‘victory’ came in as a “Solution”, to “the Durban Post Office Problem”.

Having said that, the Durban Post Office had only two entrances: one for Blacks and the other for Whites. And the Indians had to use the one Black Native Africans used. Of course, Gandhi saw that the discrimination against Indians at work and realised the necessity of the ‘third’ one.

So, he petitioned to the authorities for a ‘third entrance’ for Indians so they did not have to use the same entrance as the Black native Africans.

Indian bond indentured labourers who were under severe servitude, and were being incarcerated, flogged, starved, sexually assaulted and killed had been distanced by Gandhi. In spite of for these people who were in unspeakable misery, he soon became a mouthpiece for the wealthy trader ‘Passenger Indians’ cause. On the other hand, the White regime grew weary as the Indian population started to grow rapidly.

Meanwhile, Gandhi returned to India for a short time and was rallying about the Indians’ situation in South Africa. But got back to South Africa soon. On his way back on January 14, 1897, his ship was met with thousands of angry protestors who refused the ship dock until a negotiation that took several days to take place. He was beaten and attacked on his way home.

Until 1928, Gandhi was a strong supporter of the British Empire and a loyal subject.

As a responsible subject, he along with his ‘Passenger Indian’ friends volunteered for the British Empire when it went to war against Dutch settlers over the spoils of South Africa. The war is known as the Boer War, Anglo-Boer War, or South African War. The War was fought between the British Empire and two Boer states, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State. The results: the British troops fought Boer guerrillas, burnt down thousands of Boer farms, and slaughtered people and cattle as they swept through the lands.

Subsequently, in 1906, during the Bombatha rebellion against the British government for imposing a £1 poll tax to put pressure on Zulu men to enter into the labour market.

Gandhi who was in South Africa during the time sought Imperial permission to solidify help. He actively encouraged the British to recruit Indians. He argued that Indians should support the war efforts in order to legitimise their claims to full citizenship. The British, however, refused to commission Indians as army officers. Nonetheless, they accepted Gandhi’s offer to let a detachment of Indians volunteer as a stretcher-bearer corps to treat wounded British soldiers.

Gandhi said, “We are in Natal by virtue of the British Power. Our very existence depends on it. It is, therefore, our duty to render whatever help we can”. By contrast, instead of regretting his involvement in the Anglo-Boer and Bombatha revolt, Gandhi said he rather found Bombatha rebellion inspiring and found a foundation of his ‘celibacy’ and ‘voluntary poverty’.

Months after the Bombatha revolt ended in 1906, and despite Gandhi’s demonstration of his loyalty toward the British Empire through active service, he was let down again on the issue of ‘equal treatment towards the ‘Passenger Indians’ is concerned. The British government threw another blow bypassing, “The Transvaal Asiatic Law Amendment Act’ imposing control on Indian merchants– who were considered competitors to White traders—to enter Transvaal. The Act also implies ‘that every male Asian had to register himself and produce in demand a thumb-printed certificate of identity”.

Again, Gandhi stood for the ‘Passenger Indians’ and led by him, “two thousand people burnt their passes in a public bonfire. Gandhi was assaulted, arrested and imprisoned”.

In the prison, where he had to share a prison cell with Blacks became the worst nightmare. He wrote, “We are all prepared for the hardship, but not quite for this existence. We could understand not being classed with the Whites, but to be placed on the same level of the Natives seemed to be too much to put up with”.

After setting up his first commune Phoenix Settlement in 1904, this time around Gandhi set up his second commune, Tolstoy Farm, on 1100 acres of land gifted by his wealthy friend Hermann Kallenbach of Johannesburg. There he began his experiment on ‘purity’, ‘spirituality’, and ‘Satyagraha’.

By now Gandhi already proposed to the British government to partner in the British colony in South Africa, but the British reluctance was obvious and he was let down again. To put the zeal into the movement, he took to his opponents in the form of Truth and Love, which happened to be perfect political tools. His admiration for the British and disdain towards Black Native Africans were ever-present in everything he possibly did in the name of politics at the time.

“In 1909 Gandhi published his most favoured political tract Hind Swaraj. It was written in Gujarat and translated into English by himself. Its best and most grounded passages are those in which he writes about how Hindus and Muslims would have to learn to accommodate each other after Swaraj. This message of tolerance and inclusiveness between Hindus and Muslims continues to be Gandhi’s real, lasting and most important contribution to the idea of India.

Along with denigrating the British Parliament, in Hind Swaraj, Gandhi sketched Hinduism’s spiritual ma—the map of holy places in India. He condemns doctors, lawyers, railways and the Western Civilisation as ‘Satanic’.

In all his years in South Africa, Gandhi maintained that Indians deserved better treatment than Africans.

A changed person, “for the first time in twenty years, Gandhi aligned himself politically with the people he had previously distanced from. Indian workers who rose against a new Three-Pound-Tax and against new marriage law that made their existence illegal and their children illegitimate”.

Gandhi stepped in to ‘lead’ the strike. He travelled from town to town in South Africa, addressing coal miners and plantation workers. The strike spread everywhere, he lost control of it and his non-violent Satyagraha failed. Eventually, a settlement with Smut was signed.

Arundhati Roy writes, “That Gandhi was a hero in South Africa is as undeniable and it is baffling. In order for Gandhi to be a South African hero, it becomes necessary to rescue him from his past and rewrite it”.

Toward the end of his stay in South Africa, through the earliest biographies—one of them was written by a minister of the Johannesburg Baptist Church Reverend Joseph Doke— his contribution was moving fast toward the Messiah front. He was being favoured by missionaries and pastors in the Christian world.

As such, the young Reverend Charles Freer Andrews travelled to meet with Gandhi in South Africa and became a lifelong devotee; and went on to suggest Gandhi ‘the humblest’, ‘the lowliest and lost’, and ‘a living avatar of Christ.’

The most influential admirer of Gandhi was the Nobel Prize winner for literature Roman Rolland. Did not meet Gandhi yet, he published Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One with the Universal Being. In 1915, Gandhi returned to India via London, where he was awarded with the Kaiser-i-Hind Gold Medal for public service—an honour that he returned in 1920, before his first national non-violent movement. Honoured thus, he arrived in India fitted out as the Mahatma—the great soul—who had fought racism and imperial and stood up for the rights of Indian workers.

Ambedkar-the Radical

Gandhi’s primary political and moral challenger Ambedkar was born on April 14, 1891, in the cantonment town of Mhow new Indre in central India.

He was the fourteenth and last child of Ramji Sakapal and Bhimabai Murbadkar Sakapal. As a young boy, he grew sceptical about the Ramayana and the Mahabharata’s lesson in morality. He believed Krishna to be a fraud and that his life is nothing but a series of frauds.

“Ambedkar’s encounter with humiliation and injustice for being Untouchable began from his childhood. Thanks to new British legislation he was allowed to go to a school that belonged to privileged castes but forced to sit apart from his classmates on a scrap gunnysack so that he would not pollute the classroom floor. He would remain thirsty all day because he was not allowed to drink from Touchable’s tap. Sarata’s barbers would not cut his hair, not even the barbers who sheared goats and buffaloes.

His older brothers were not allowed to learn Sanskrit because it was the language of the Vedas.

While he was doing his bachelor’s degree at Elphinstone College, a well-wisher introduced him to Sayajirao Gaekwad, the progressive Maharaja of Baroda. The Maharaja gave him a scholarship of Rs 25 a month to complete his graduation.

When Ambedkar graduated, he became one of the three students who was given a scholarship by Sayajirao Gaekwad to travel abroad to continue his studies. In 1913 the boy who had to sit on a gunnysack on his classroom floor was admitted to Columbia University in New York.

Ambedkar returned to Baroda in 1917. “To repay his scholarship, he was expected to serve as military secretary to the Maharaja. He came to a very different reception from the one Gandhi received. There were no glittering ceremonies, no wealthy sponsors. Afraid of even accidentally touching Ambedkar, clerks, and peons in his office would fling files at him. Carpets were rolled up when he walked in and out of office so that they would not be polluted by him”.

He found no accommodation in the city: his Hindu, Muslim and Christian friends, even those he had known at Columbia turned him down. Unable to find accommodation in Baroda, Ambedkar returned to Bombay, where, after initially teaching private tutorials, he got a job as a professor at Sydenham College in Bombay.

Ambedkar believed that the practice of untouchability is the real violence of caste and its denial of entitlement: to land, to wealth, to knowledge, to equal opportunities.

“How can a system of such immutable hierarchy be maintained if not by the threat of egregious, ubiquitous violence? Why would an Untouchable labourer, who is not allowed to even dream of being a landowner one day, put his or her life at the landlord’s disposal, to plough, to sow the seed and harvest the crop, if it were not out of sheer terror of the punishment that awaits the wayward? The answer: by being flogged, by being lynched, and if that did not work, by being hung from a tree for others to see and be afraid. Why Dalits are even today being burnt alive, raped, dismembered and paraded naked”?

Ambedkar, the originator of Annihilation of Caste, provided the answer:

“…..There is only one answer which I can give and it is that the lower classes of Hindus have been completely disabled for direct action on account of this wretched caste system. They could not bear arms, and without arms, they could not rebel. They were all ploughmen—or rather condemned to be ploughmen—and they were never allowed to convert their ploughshare into swords.

They could not think out or know the way of their salvation. They were condemned to be lowly; and not knowing the way of escape, and not having the means of escape, they became reconciled to eternal servitude, which they accepted as their inescapable fate”.

Ambedkar, who had been fighting for equality of the Untouchables, time and again reasoned that equality is possible only if the system of four castes is annihilated. He said, “To sum up, untouchability is not a simple matter, it is the mother of all our poverty and lowliness and it has brought us to the abject state we are in today. If we want to raise ourselves out of it, we must undertake this task. The inequality inherent in the four-caste system must be rooted out”.

The hope and aspiration of Ambedkar for a separate electorate for the Untouchables and Dalits never saw daylight because of the Congress’s opposition under Gandhi’s leadership; and Brahman conspiracy against Shudras.

Ambedkar’s Independent Liberal Party (ILP) fall fray to Brahmanised Communism and Hindu conservatives’ chauvinism propaganda.

On the other hand, Gandhi could not dissociate his position from the privileged caste and was trying to convey the message of liberalism by holding aloft the Bhagavad Gita dearly while promoting inclusive views.

Raja Rammohun Roy, who was unarguably the first great Indian modernist, campaigned for the abolition of Sati, for greater rights for women more generally, for the embrace of modern scientific education and for a liberal spirit of free enquiry and intellectual debate. His example was carried forward by other Bengali reformers, among them Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Swami Vivekananda, who focussed on, among other things, education for women and the abolition of caste distinctions.

And what Gandhi, as Mahatma, did can never be compared with their works. Instead of trying to abolish Casteism, he was advocating political inclusivism while backing caste-based privileges. He had never willed to cure the ailment of caste-system.

Therefore, coupled with Karma, the Untouchables, the Dalits, the Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Castes are to continue their survival in an unending cycle of misery.

The chasm of that hierarchical dominance garners firmer roots in the contemporary form of nationalist politics. Supported by Hinduism it gets wider as liberalism becomes thinner and cornered with exclusive political ideas, which is being resurfaced time and again in Indian contemporary politics.

Reception of The Doctor and the Saint

When The Doctor and the Saint was first published as a preface, it sparked immediate controversy and debate across India’s literary, political, and activist spheres. Some critics, particularly those loyal to Gandhi’s image, accused Roy of historical revisionism, of being too harsh or one-sided. Others praised her for breaking the long silence around Gandhi’s caste politics and for boldly bringing Ambedkar into sharper global focus.

For many Dalit scholars, activists, and readers, Roy’s work was a vindication—finally, someone from India’s elite literary circles had used her platform to articulate what had long been spoken in the margins. Her forensic unpacking of Gandhi’s writings, especially those penned in Gujarati and seldom translated or critiqued, shed new light on his beliefs about varna (caste-based division of labor), hereditary occupation, and social hierarchy.

The book has been widely taught, cited, and referenced in international discourses on caste, social justice, and decolonial studies. Haymarket Books’ decision to publish the essay for a Western audience was strategic: it challenged the sanitized Western narrative of Gandhi as a universal symbol of peace and nonviolence, presenting instead a complex and morally ambiguous portrait.

However, Roy’s critique of Ambedkar’s embrace of modernity—his faith in the state, industrialization, and legal reform—also drew concern from leftists and Marxist thinkers. Some believed she had oversimplified the revolutionary scope of constitutionalism or had subtly romanticized a rural anti-modernist vision.

Nevertheless, the book’s reception overall remains overwhelmingly positive in progressive, anti-caste, and academic circles, earning Roy renewed respect as both a writer and a public intellectual.

Conclusion: Why The Doctor and the Saint Matters

Reading The Doctor and the Saint is not an easy experience—it is raw, confrontational, and, at times, deeply uncomfortable. And that is precisely its power. Roy forces us to confront not just historical injustice but the myths we continue to inhabit.

This is not a book that merely documents caste—it disrupts the silence around it. It asks: Why has caste not provoked the same international outcry as apartheid? Why is Ambedkar not universally studied the way Gandhi is? Why does modern India continue to function through the hierarchies of caste, dressed up now in corporate suits and digital euphemisms?

Roy’s intellectual courage lies in her refusal to let comfort dilute truth. She does not romanticize Ambedkar; nor does she spare Gandhi. Instead, she lays bare the ideological struggle between a man who demanded the annihilation of caste and a man who sought to preserve it with a gentle face.

In a world where inequality is increasingly normalized, The Doctor and the Saint reminds us that radical clarity is not just useful—it is necessary. Roy’s essay is a call to read Ambedkar not as a footnote to Gandhi, but as a fierce philosopher of liberation in his own right.

And for that alone, this book deserves to be read, taught, debated—and remembered.

It is a great work for expanding one’s horizon in knowing something unknown about two great souls in the Indian Subcontinent.