Last updated on November 19th, 2025 at 03:26 pm

The Godfather is the book you pick up when you’re tired of neat moral lines and want to understand why people break the law for love, loyalty, and survival.

It solves a very modern problem: how to think clearly about power, family, and violence in a world where institutions fail and “respect” can feel more real than the law.

If you’ve ever wondered how a criminal can be both monstrous and strangely admirable, Mario Puzo’s The Godfather book gives you a disturbingly persuasive answer in the form of the Corleone family saga.

At its core, this is a novel about the cost of security—what it takes to protect “your own” when the state won’t or can’t. The Godfather book shows that the line between protector and predator is terrifyingly thin: in a corrupt world, the same ruthless power that shields a family also damns the person who wields it.

Puzo’s genius is that he doesn’t preach this; he makes you feel it through Vito and Michael Corleone’s choices, so that by the end you’re unsettled not only by what they do—but by how much of it you found yourself silently justifying.

The novel stayed on The New York Times best-seller list for 67 weeks and sold over nine million copies in its first two years, ultimately reaching around 21 million copies worldwide—numbers that make it one of the most commercially successful works of modern fiction.

Its vision of organized crime helped define the public imagination of the Mafia, with critics and historians noting how Puzo’s portrayal of power, loyalty, and immigrant struggle reshaped American cultural mythology.

The 1972 film adaptation, drawn closely from the novel, became the highest-grossing film of the year and remains among the most acclaimed movies ever made, amplifying the book’s influence across generations.

The Godfather This book is ideal if you’re drawn to morally complex stories, crime sagas, and slow-burn character transformations, and if you want a deep, atmospheric exploration of Italian-American family life and the inner workings of a criminal empire.

It’s not for readers who need clear-cut heroes, who dislike violence and patriarchal worlds, or who prefer fast, plot-only thrillers with minimal psychological depth.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

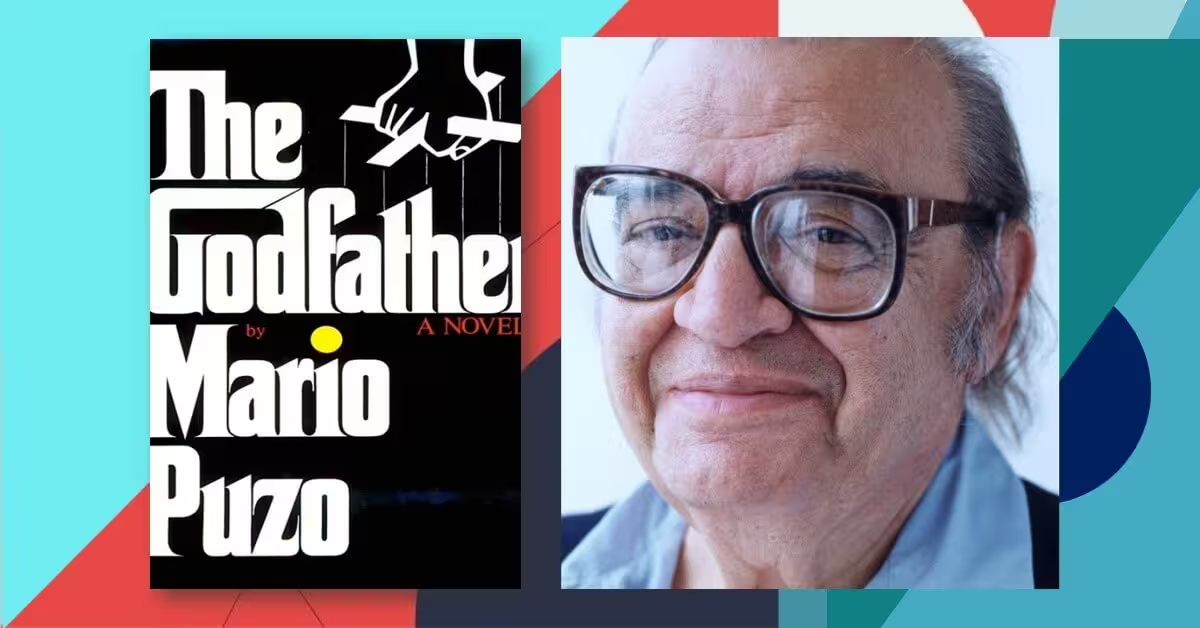

Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, first published in 1969 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, is a sprawling crime novel about the rise and transformation of the Corleone crime family in mid-20th-century America.

Set primarily in New York and later Las Vegas and Sicily, the book follows Don Vito Corleone, his sons Sonny, Fredo, and Michael, and the web of allies, enemies, and dependents who orbit their power.

Though often remembered through the shadow of Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Puzo’s novel stands on its own as a dense, often brutal, and surprisingly tender exploration of family, honor, and the American Dream gone sideways.

The Godfather’s continuing presence on “greatest books” lists—from crime-novel rankings to popular surveys like PBS’s The Great American Read and compilations of must-read classics—confirms that it has crossed from “Mafia story” into modern canon.

2. Background and Historical Context

The Godfather book by American writer Mario Puzo is a crime novel published in 1969. The book portrays the rise of the greatest, most respected and most powerful Mafia Don in New York City, and the war between six powerful mafia families after WWII. I read the book after watching the film first and realised why the film happens to be a great piece.

Without the book, the knowledge of the film may remain incomplete. The book is a thorough description of guns, mafia activities, gambling, abortion and the bending of state elements to corruption, to the power of the underworld.

I came to know why The Godfather (1972) is a great movie only when I read the book on which it is based. One may not find the film as good as people say it would be. But reading the book would certainly make them say, “Don’t judge a book by its film.”

Puzo wrote The Godfather at a time when Italian-American organized crime was both a real political force and a media obsession, shaped by high-profile mafia hearings and sensationalist coverage.

The novel is set mainly between 1945 and the mid-1950s, opening just after World War II and tracing the shift from old-world, neighborhood-based rackets to a more corporate, nationalized crime structure grounded in narcotics, gambling, and Las Vegas casinos.

Historically, this was the moment when returning soldiers like Michael Corleone were trying to build respectable postwar lives while the U.S. government belatedly acknowledged the reach of organized crime, and Puzo grafts his fictional Corleones onto that real-world tension.

Puzo himself was a second-generation Italian-American who said he had never met a real mafioso before writing the book; instead, he drew on newspaper reports, hearings, and the mythic aura of the Mafia, then supercharged it with family drama and operatic stakes.

3. The Godfather book Summary

The novel begins with a wedding and a queue of desperate petitioners.

On the day of his daughter Connie’s wedding, Don Vito Corleone sits in his Long Beach compound granting favors—an undertaker begging for revenge, a baker asking help to keep his future son-in-law in the country, and others whose debts and loyalties form the invisible scaffolding of his power.

Around him, we meet the rest of the family: hot-headed heir Sonny, dutiful but weak Fredo, and youngest son Michael, who sits apart with his New England girlfriend Kay Adams, making it clear he wants no part in the family business.

Michael, a decorated Marine officer who defied his father by joining the war, is introduced as both proud of and distanced from the Corleone “empire”—he tells Kay matter-of-factly about his father’s ruthless tactics, like forcing a bandleader to release singer Johnny Fontane from a predatory contract, but ends with: “That’s my family, Kay, not me.”

This early tension—between Michael’s love for his family and his desire to live within the law—sets up the arc that will define the entire book.

Soon, a new business opportunity arrives in the form of Virgil Sollozzo, “The Turk,” backed by the rival Tattaglia family.

Sollozzo wants Don Corleone’s political protection and capital to move into narcotics, promising high profits, but Vito refuses, insisting drugs will bring down too much police and public heat and corrupt his carefully cultivated political alliances.

His refusal is interpreted as a threat to Sollozzo’s future empire, and a failed assassination attempt leaves the Don gravely wounded and the delicate power balance shattered.

With Vito incapacitated, Sonny steps in as acting head, unleashing a wave of violence.

Sollozzo kidnaps family consigliere Tom Hagen and pressures him to convince Sonny to accept the drug deal, believing Sonny is hot-headed but pragmatic.

The attempt on Vito’s life and a subsequent brutal attack on Vito’s loyal enforcer, Luca Brasi, spark a Mafia war across New York, as the Corleones face coordinated attacks from rival families aligned with Sollozzo and the corrupt police captain McCluskey.

Michael, who has stayed deliberately peripheral, is pulled in when he goes to the hospital to visit his father and discovers the guards withdrawn and a second attempt on Vito’s life imminent.

He bluffs his way into protecting his father with the help of a terrified nurse and a few civilian friends, then is punched by McCluskey in public, giving him a broken jaw and a permanent mark of police corruption.

This is the hinge moment: Michael decides that the only way to save his father and the family is to do what none of the others can do—personally kill both Sollozzo and McCluskey.

The infamous restaurant scene follows.

Under the guise of a peace talk, Michael meets Sollozzo and McCluskey in a Bronx restaurant; a hidden gun has been planted in the bathroom.

After a tense conversation half in Italian, Michael fetches the weapon, emerges, and shoots both men at close range, crossing the point of no return—from civilian son to made killer—then is smuggled out of the country to hide in Sicily.

In Sicily, the novel slows and deepens into a different kind of story.

Michael travels under the protection of the local Mafia, under the eye of Don Tommasino.

He falls in love with Apollonia, a village girl whose beauty Puzo describes in almost religious terms, and marries her in a traditional Sicilian ceremony, briefly tasting a simple, almost pastoral happiness far from American power struggles.

But this peace is an illusion: a betrayal leads to a car bomb meant for Michael that instead kills Apollonia, and Michael’s exile becomes a raw wound of grief and paranoia.

Back in the United States, the Corleone war escalates and exacts its price.

Sonny, enraged by Connie’s abusive husband Carlo, races out alone to punish him and is ambushed at a toll plaza, riddled with bullets in one of the novel’s most shocking scenes.

Vito, recovering and shattered by his eldest son’s death, reassesses his strategy: realizing that further war will destroy his remaining family, he sues for peace with the other Mafia bosses at a summit, accepting territorial losses and agreeing to allow narcotics in limited ways to preserve his line.

Michael eventually returns from Sicily at his father’s request.

He reconnects with Kay, who has tried and failed to move on; Puzo shows her as both fascinated and frightened by the Corleone world, yet still in love with Michael.

They marry and have children, while Vito quietly prepares Michael as his successor—not in the legitimate path Michael once imagined, but as the next Don, the one strong enough to do what Vito can no longer bring himself to do.

As Vito ages, the family business shifts west toward Las Vegas.

Michael, outwardly mild and controlled, takes charge of negotiations with casino owner Moe Greene, asserting that “the Corleone family has big dough invested here” and making it clear that he intends to centralize power around himself.

Fredo, already seen as weak and compromised, embarrassingly sides with Greene against Michael, prompting Michael’s chilling warning: “Don’t ever take sides with anybody against the Family again.”

These scenes show Michael’s transformation from reluctant son to cold strategist.

When Vito finally dies in his garden, after telling Michael that “life is so beautiful,” Michael stands at the funeral observing mourners and resolves to protect his future children while never fully trusting the wider world.

The old Don’s death triggers the endgame: the rival families misread Michael as weaker than his father and move to finish the Corleones, not realizing how far ahead he has planned.

The climax is one of modern fiction’s most famous sequences.

During the baptism of Connie and Carlo’s baby, Michael stands as godfather, renouncing Satan and all his works in church while, on his orders, his men systematically assassinate his rivals across the city—Barzini, Tattaglia, and their key allies, as well as Moe Greene in Las Vegas.

In the aftermath, Michael confronts Carlo about Sonny’s murder, gently extracting a confession and then having him killed—fulfilling Vito’s unspoken demand for revenge and consolidating total control.

Kay, unnerved by the wave of deaths, directly asks Michael if he had Carlo killed.

Michael, now fully Don Corleone, lies to her face.

In the novel’s quietly devastating final image, Kay watches as caporegimes arrive to kiss Michael’s hand and address him as “Don Michael,” while his men literally close the door on her, shutting her out of the true nature of her husband and his world.

The boy who once insisted “that’s my family, not me” has become the very thing he wanted to escape.

But Michael was determined to avenge Sonny’s death and take control of New York City by being the most powerful mafia family, which he did after the Don’s death.

Breaking the agreement, he first killed Fabrizzio, who fled to America from Sicily after the assassination attempt. Then he went after Barzini and Philip Tattaglia, his brother-in-law Carlo, and his caporegime, Tessio, who was set up to kill Michael. After that, the Corleone family shifted to Las Vegas from Long Beach.

4. The Godfather Book Analysis

4.1 The Godfather Characters

Vito Corleone is written as a paradox: a ruthless criminal who inspires deep loyalty.

Puzo shows him as a man who will threaten a bandleader with having either his “signature or his brains” on a contract yet is also remembered by ordinary people—like Filomena, saved from Luca Brasi—as someone whose name they “bless” and pray for every night.

He is the embodiment of a self-created sovereign, operating alongside and often above the state, whose justice is harsh but predictable, and that predictability is precisely what makes people choose him over the formal legal system.

Michael’s arc is the emotional and moral engine of the book.

Initially, he’s the son who “had all the quiet force and intelligence of his great father” but insists on serving America in the Marines against his father’s wishes, and he keeps Kay at arm’s length from the family business.

His journey—from bemused outsider at his sister’s wedding to calculating Don—is carefully staged: the hospital vigil, the restaurant murders, the Sicilian exile, the return to Kay, the casino negotiations, and the final baptism-massacre all mark stages where necessity becomes habit, and self-sacrifice for the family morphs into a taste for power.

Sonny, Fredo, Tom Hagen, and Kay round out a deliberately unbalanced “family system.”

Sonny is passionate and generous but fatally impulsive; Fredo is loyal but weak, lacking the “animal force” needed for leadership; Tom is the adopted Irish-German consigliere, cool-headed and pragmatic, always trying to frame violence in the language of business and law.

Kay, meanwhile, is our partial moral stand-in: an outsider whose “sharply intelligent” face and Protestant New England background make her both fascinated by and fundamentally misaligned with the Corleone code, which is why her ultimate exclusion at the end hits so hard.

Supporting characters like Johnny Fontane, Moe Greene, Luca Brasi, and the rival dons (Barzini, Tattaglia) serve to map the ecosystem of power—each showing a different way to handle success, fear, aging, and betrayal within this world.

4.2 The Godfather book Themes and Symbolism

One of the central themes is the ambiguity of crime and justice.

Critical studies note that Puzo’s narrative complicates any simple division between “good guys” and “bad guys,” instead presenting the Corleones as both perpetrators and protectors, with Michael’s decisions often framed as grim but rational responses to treachery and systemic corruption.

The state is present but often incompetent or corrupt (think McCluskey), so the family’s extralegal violence is positioned as an alternative justice system, albeit one that corrodes its practitioners from the inside.

Family and loyalty form the emotional core.

Scholarly commentary emphasizes that in The Godfather, family loyalty is both sacred and weaponized: Vito’s insistence on family unity becomes the justification for Michael’s increasingly brutal actions, while betrayals (Tessio, Carlo) are punished with absolute finality.

The tragedy is that the same loyalty that protects the family also traps them—Kay’s anguish stems precisely from her realization that, to Michael, the family’s survival always trumps individual moral qualms.

There’s also a recurring exploration of the American Dream.

Britannica and other analyses point out that Puzo frames the Corleones as immigrants who achieve power and prosperity through the only channels fully open to them—racketeering, gambling, protection—creating a dark mirror of capitalist success.

They provide jobs, favors, and medical care; they also extort, bribe, and kill, making the reader wrestle with how much of their “success” differs in kind—not just degree—from legitimate business empires.

Symbolically, the book is filled with rituals and thresholds.

Weddings, funerals, baptisms, and family dinners mark transitions in power and loyalty, with the closing door on Kay symbolizing the sealing of Michael’s new identity and the final boundary between his public façade and private truth.

Sicily itself functions as both origin and exile—a place where the old codes are purer but where vengeance radiates across generations, reminding us that violence is not just an American aberration but part of a longer Mediterranean tradition of honor and retribution.

5. Evaluation

5.1 Strengths / Positive Reading Experience

The most obvious strength is the sheer narrative propulsion.

Even knowing the plot from the films, I found the novel’s quieter stretches—Michael teaching Apollonia to drive inside the villa walls, Kay’s lonely wait in New England, Tom Hagen’s calm legal briefings—as gripping as the gunfights because Puzo makes every scene feed into the emotional logic of power and loyalty.

Characterization is another major asset: Vito’s mix of gentleness and menace, Michael’s slow hardening, Kay’s conflicted conscience, and even relatively minor figures like Filomena or Nazorine feel textured rather than decorative.

The book also excels at world-building—political favors, judges on retainer, undertakers who “owe” the Don for arranging green cards—all these details create a convincing shadow-economy that explains why people turn to a man like Corleone in the first place.

Stylistically, Puzo’s prose is deceptively plain, which works well for SEO-style clarity: sentences tend to be direct, concrete, and saturated with action, making the complex plot surprisingly easy to follow.

Finally, the emotional impact is real: Sonny’s death, Apollonia’s explosion, Vito’s quiet passing, and Kay’s final realization hit with the weight of a family saga, not just a crime thriller.

5.2 Weaknesses / Negative Reading Experience

The novel isn’t flawless, and being honest about that makes the praise ring truer.

Some sections—particularly the Johnny Fontane subplot and parts of the Hollywood detour—can feel like digressions that slow the main Corleone arc, even if they do flesh out the theme of show business as another form of power game.

Female characters, though sometimes vivid in the moment, are generally underdeveloped compared to the men; Kay, Connie, and Apollonia are defined more by their relationships to male choices than by their own sustained interior lives.

There’s also a real risk that readers can romanticize the Mafia here, because the narrative lens is so steeped in respect, family, and honor that the structural exploitation—sex work, drugs, extortion—can fade into the background if you’re not paying attention.

And while the book is page-turning, some transitions (like Michael’s final emotional state after ordering multiple murders) rely more on the reader’s inference than on deep, introspective passages, which can leave you wanting more psychological excavation.

5.3 Impact: Emotional and Intellectual

Emotionally, reading The Godfather book left me with a double ache.

On one level, I felt the sadness of watching Michael’s humanity narrow—seeing the boy who once wanted a normal, law-abiding life become the man who can calmly justify killing his brother-in-law and lying to his wife to “protect” her.

On another level, I felt the uncomfortable recognition that the book is asking a question we still haven’t answered: what do we do when formal institutions don’t feel protective, and how far are we willing to go to protect our own.

Intellectually, the novel pushed me to think about organized crime less as “monsters in suits” and more as an alternative governance structure that emerges when trust in the state is low.

That doesn’t excuse anything, but it explains a lot—especially in immigrant and marginalized communities where access to lawful power was historically limited.

5.4 Comparison with Similar Works

Compared to other crime epics—say, Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River or James Ellroy’s L.A. Confidential—The Godfather is less noir and more tragedy, closer in spirit to a family chronicle like Buddenbrooks with guns.

It differs from many modern thrillers by caring more about lineage, ritual, and generational change than about solving a particular mystery.

Compared to contemporary “organized crime” media, like The Sopranos, Puzo’s world is more mythic and hierarchical: Tony Soprano’s therapy sessions constantly undercut his own mythology, while the Corleones are allowed a more operatic grandeur, even as the book quietly shows their costs.

It also sits interestingly alongside non-fiction like Selwyn Raab’s works on the American Mafia, which confirm that while Puzo dramatizes heavily, the basic infrastructures—families, caporegimes, bosses, political protection—have roots in real criminal organizations.

So, if you’re mapping your reading life, The Godfather lives at the crossroads of family saga, political novel, and crime thriller.

5.5 Adaptation: Book vs. Film & Box Office

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 film adaptation is famously faithful to the spine of Puzo’s story but more selective in its subplots.

The movie foregrounds Vito and Michael, compresses or cuts some novel material (like extended Johnny Fontane arcs and deeper Vegas business details), and intensifies certain images—the severed horse’s head, the baptism montage—into cinematic icons.

Where the book spends more time inside various minor characters’ lives, the film sharpens the focus and uses visual symbolism (lighting, framing, music) to convey the moral descent that Puzo often handles through exposition and dialogue.

In terms of commercial and cultural impact, the film was a phenomenon: it became the highest-grossing U.S. film of 1972 and has earned around $270 million worldwide at the box office (not counting decades of home-video and streaming revenue).

AFI and other rankings regularly place it near the very top of “greatest films of all time,” which in turn drives new readers back to Puzo’s original novel, making this one of the most mutually reinforcing book-film relationships in modern culture.

If you love the film, the book will feel like both a richer backstory and a slightly harsher mirror.

Is the social system doing any good?

There many things that the movie does to tell us about. Suppose, we do not know how the great Don Corleone became the Godfather, we don’t know his greatness, generosity, ferocity and being Godfather became his only ‘destiny’.

On the other hand, there are many things that can compel one to ponder upon the book, such as, how one can easily feel safer in an empire of a godfather, than in a society where justice is meted out by the protectors of it.

The Don would often advise, ‘one can have but only one destiny in life’, and we have to find out what that is. The Godfather, after all tell us why godfather are the gods for the godless, deprived and honest people who are made victims of social and political injustice.

When the state’s justice system fails to protect and provide the weaks the justice, when society never pays heed to the insignificant people, they came to him seeking justice. And his gunmen duly take care of matters.

He got criminals bailed from death row by manipulating and influencing the judiciary system, and getting them a high position in his organisation.

He became the benefactor to many and a saviour in the society he created. A society where there is no rule of law but orders of power and mutual empowerment.

The Godfather portrays a grim reality that a man, a man with a family inevitably faces in meeting the end demands of his wife, children and well-wishers.

A humble hardworking man, Vito, rose to be the Don Corleone amid his desperation to arrange a square meal in his children’s mouths, and during the time of miscarriage of justice. He saw how mafias, and ruffians were being feared, and respected and were playing with so-called state functionaries.

The film does not tell how an honest police captain, McCluskey, became a protector of mafias, instead of a guardian to the state’s people. Being underpaid by the state he decided to be under Sollozzo’s payroll and became the protector the crime and criminals which helped him send his children to a better college, his wife to have better clothes and convey his assistance to his sister and relatives who were under his obligations.

Yet, how the Don rose, McCluskey got involved in illicit activities and why Felix got himself involved in fraudulent activities may be judged by moral and social standards, and we may dictate them as a matter of choice.

But when a man cannot avert his responsibilities of caring other who are deepened on him, and when he thinks his children deserve a little more privilege, he is ready to do anything possible to that end.

However, certainly is not to justify the crimes. Society usually remains dead to the needs of its community but suddenly becomes conscious of the crimes that help mitigate the needs of the people.

Whatever is bad, illegal, and unaccepted found a way to be benevolent in the Don’s word, which is somehow also benevolent to great many people. That, “family is more loyal and more to be trusted than society”, somehow rings true to me.

Mario Puzo, or the greatness of the great Godfather Don Corleone in that matter, reminds us that once the state fails to protect the powerless; provide justice; and cronyism, corruption and selective application of law infiltrate the system, the powerless aspire to become powerful take role of the state administration.

The Dons or the underworld promise to give justice with guns and general chaos. Godfathers rise with greatness!

6. Personal Insight

One angle where The Godfather feels surprisingly current is in teaching about informal power systems and parallel institutions—a topic that crosses literature, political science, sociology, and even business ethics.

Modern research into organized crime and corruption often emphasizes that criminal groups thrive where official institutions are weak, slow, or distrusted, stepping in to provide “services” like credit, protection, or dispute resolution.

In classrooms, I’ve seen how using The Godfather alongside contemporary case studies—say, analyses of mafia-type organizations in Italy, Mexico, or even digital “mafias” controlling online fraud—helps students grasp that these systems are not random evil but structured responses to gaps in governance.

You can pair the novel with resources on organized crime and governance failures from bodies like the UNODC or academic overviews of how criminal networks embed themselves into formal economies.

There’s also a very personal educational lesson for readers navigating today’s blurred lines between legal and “merely shady” behavior in politics or corporate life: Puzo shows how easily you can rationalize each step (“just this one killing,” “just this one cover-up”) in the name of loyalty, until you look up and realize you’ve become someone unrecognizable to your younger self.

For educators, The Godfather works not just as a crime story but as a case study in ethics under pressure—ideal for interdisciplinary courses on leadership, power, and moral compromise, and highly resonant for readers who look at current scandals and think, “How did it get that far?”

7. The Godfather book Quotes

- On Michael’s quiet power: he has “the quiet force and intelligence of his great father,” a reminder that the most dangerous people are often the calmest ones in the room.

- On the nature of favors: the Don compares his favors to caches “scattered on the route to the North Pole,” to be used when needed—an unforgettable image of pre-paid loyalty.

- On Vito’s late-life philosophy: “If I can die saying, ‘Life is so beautiful,’ then nothing else is important,” a line that makes his whole violent career feel even more unsettling.

- On Kay’s disillusionment: she leaves Michael “because he made a fool of me… he lied to me,” capturing how betrayal of trust, more than violence itself, is what she cannot forgive.

- On Michael’s duty, as Hagen explains it: “Treachery can’t be forgiven,” because people who betray once can’t forgive themselves and will always be dangerous—a chilling rationalization that neatly sums up the book’s moral logic.

8. Conclusion & Recommendation

Taken as a whole, The Godfather is more than a “Mafia novel”; it’s a dark, compelling meditation on power, loyalty, and the price of keeping a family safe in an unsafe world.

If you’re a fan of character-driven fiction, crime sagas, or books that blur the line between heroism and monstrosity, this should be high on your list; if you prefer hopeful, clearly moral universes, you may find it impressive but emotionally draining.

Its significance lies not only in its massive sales and iconic film adaptation but in how deeply its images and phrases have seeped into everyday speech and thinking about power—from “offers you can’t refuse” to the idea of “family business” as both sanctuary and trap.

I’d recommend it especially to readers interested in the intersection of literature, politics, and ethics—anyone who wants to understand why the myth of the honorable gangster remains so seductive, and why, after closing the book, that seduction should make us uneasy.

The Godfather by Mario Puzo is one of the best novels to elaborate, ‘behind every fortune there is a crime’. Mario offers exact reasons why we should endear him for his work, while The Godfather tells us it has to offer society a lesson that way it operates within the framework of corrupt regulators to control the will the mass.

And every favour one receives from any Don must be repaid by even greater favour by the recipient. No favour is lavishly given unless the benefactor sees there is a possibility of getting it returned in the near future when in demand.