The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure

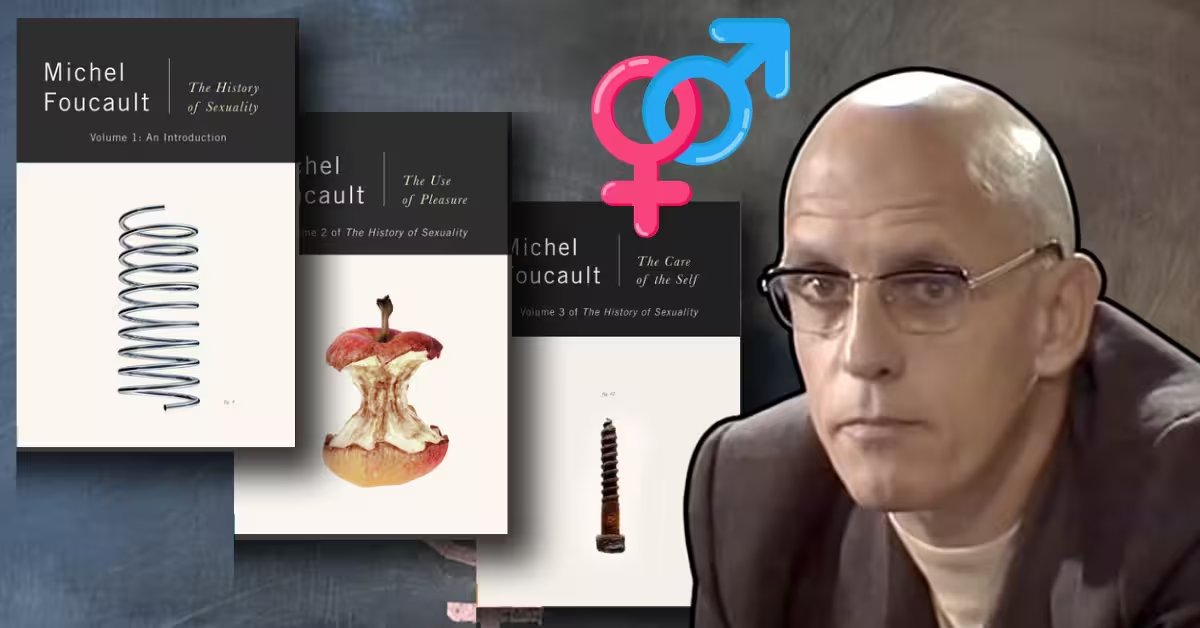

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure is the second installment in Michel Foucault’s monumental series exploring the genealogy of sexuality. Published originally in French as L’Usage des plaisirs in 1984 and later translated by Robert Hurley, this volume takes a profound turn from the first book’s focus on modernity to a historical excavation of ancient Greek and Roman ethics of sexual conduct.

Michel Foucault—philosopher, historian, and one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century—uses this book not only to elaborate his theories of power and subjectivity but to shift from repression to self-fashioning.

This is not just another philosophical inquiry—it’s a radical reevaluation of how we understand ourselves through our desires. Foucault, a French intellectual who taught at the Collège de France and wrote across disciplines such as history, philosophy, political theory, and sociology, is perhaps best known for his work on institutions, discourse, and biopolitics. With The Use of Pleasure, he transitions from the analytics of power to what he calls an “ethics of the self.”

In contrast to Volume 1, which analyzed how sexuality was regulated through institutions and discourse in modern Western societies, Volume 2 investigates how ancient societies—primarily Classical Greece—conceptualized sexual pleasure (aphrodisia) not in terms of repression but through modes of conduct, self-mastery, and ethical self-care.

Purpose

Foucault’s central thesis in this volume can be summarized as follows: In classical antiquity, sexuality was not regulated by external institutions like the church or the state, but through personal practices of ethics and aesthetics of existence. He writes:

“Why, then, this concern with sexual activity if it was not because it was linked with something else, something more important, and that had to be taken into account?”

In other words, ancient cultures viewed sexual behavior as a domain in which individuals cultivated their relationship with themselves, others, and truth. Foucault argues that understanding this shift—from institutional repression to individual ethical work—offers valuable insight into the nature of subjectivity and power today.

In this review, I aim to explore Foucault’s ideas as a human who is profoundly affected by them—not just intellectually, but personally. His exploration of how ancient Greeks approached pleasure, self-discipline, and ethical living prompts us to question the very ground on which modern sexuality stands. As someone who has read this book not for mere academic utility but for philosophical sustenance, I will guide you through its depths so that you won’t need to return to the source—unless, of course, Foucault’s voice haunts you the way it does me.

Summary

To read The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault is to encounter not just a study in sexual ethics, but a blueprint for understanding how human beings relate to themselves through desire. While The History of Sexuality Volume 1 focused on the way modern institutions used sex to exert power, Volume 2 turns toward the ancient world—primarily classical Greece—to investigate a very different form of sexual governance: the ethics of self-care.

Introduction: Shifting the Focus from Prohibition to Ethics

In the Introduction, Michel Foucault outlines a major shift from his first volume. While Volume 1 focused on how sexuality was regulated through discourse and power in modern Western society, Volume 2 pivots to antiquity, particularly Greek and Roman cultures, to examine how individuals historically constituted themselves as ethical subjects of sexual conduct. This transition from a “politics of sex” to an “ethics of pleasure” is a key theme.

Foucault introduces the concept of the “ethical substance”—the part of the self that is problematized in moral conduct. He identifies four critical components in the formation of ethics:

- Ethical Substance – what part of ourselves we see as needing regulation (e.g., desires).

- Mode of Subjection – how we relate to moral codes (e.g., divine law, rational self-governance).

- Self-Forming Practices – what techniques or disciplines are used to become moral.

- Telos – the intended outcome or moral goal (e.g., wisdom, moderation, purity).

Foucault argues that ancient sexuality was not governed primarily by legal prohibitions or religious doctrines, but by aesthetic and ethical considerations—how one should conduct oneself in pursuit of pleasure while maintaining social harmony and self-mastery.

Part One: The Moral Problem of Pleasure

In Part Four: The Moral Problem of Pleasure, Michel Foucault concludes his exploration of ancient ethics by focusing on how pleasure itself became a subject of moral concern in Greco-Roman thought. Unlike modern morality, which often frames pleasure—particularly sexual pleasure—as inherently suspect or taboo, classical thinkers approached pleasure as a problem to be managed ethically rather than a sin to be condemned outright.

Foucault begins by clarifying that in ancient ethics, particularly among Greek philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics, pleasure was not condemned in itself. Instead, it was viewed as potentially dangerous because of its power to disrupt self-mastery and rational control. Pleasure could lead to excess, dependency, and a loss of freedom if not properly regulated.

The moral question, therefore, was: How should one enjoy pleasure without becoming enslaved by it? This led to a rich tradition of ethical discourse centered on moderation (sōphrosynē), self-restraint, and the cultivation of inner harmony. Foucault shows how these concepts formed the basis of what he calls “arts of existence”—practices by which individuals shaped their lives into coherent, aesthetically pleasing, and virtuous wholes.

In this view, the self was not a static entity governed by external rules, but something to be actively crafted and cared for. Sexual pleasure was one dimension of this broader ethical project, and moral virtue consisted in achieving the right balance between desire and rationality. Crucially, Foucault notes that pleasure was not just tolerated—it was expected, even celebrated, so long as it was kept within the bounds of reason, health, and honor.

He emphasizes that the ethical evaluation of sexual acts depended on the subject’s position, age, status, and the broader context of their life. For example, a married man was expected to exercise different kinds of restraint than a young bachelor, and sexual relationships had to align with broader social hierarchies and values. What mattered most was not the act, but the mode of being and self-regulation it expressed.

Foucault contrasts this ancient ethics with modern Christian morality, which often centers on obedience, confession, and guilt. Where Christian thought frames the self as something to be subdued in accordance with divine law, Greco-Roman ethics framed the self as something to be mastered and beautified through personal discipline.

This final part of Volume 2 underscores Foucault’s central thesis: that sexual ethics are historically contingent, shaped not by universal truths but by specific cultural practices and forms of subjectivity. By studying how the Greeks approached pleasure, he offers a powerful alternative to modern sexual morality, one grounded in self-care, moderation, and ethical intentionality rather than repression or guilt.

Part Two: Dietetics

In Part One: Dietetics, Foucault examines how ancient Greek society linked sexuality with health through dietary practices. The regulation of food and sex were closely associated, as both were seen as essential to maintaining bodily equilibrium and moral order.

Greek thinkers, particularly in the medical tradition, promoted moderation in all forms of bodily intake—whether it was food, drink, or sex. Sexual activity was considered a natural function, but only when it was practiced in moderation and with regard to one’s constitution, age, and lifestyle. Excessive sex could destabilize the body and, by extension, the soul.

Dietetics was therefore not just about health in a biological sense, but part of a broader ethics of self-care. Sexual restraint and rational control were essential virtues for the free male citizen, reflecting ideals of self-mastery and rationality that were central to classical ethics.

Foucault emphasizes that in this framework, power operated not through prohibition, but through guidance and self-regulation. Individuals internalized these codes as part of their moral and physical development. This reflects a significant contrast with modern views of sexuality, which are shaped by confessional discourse and external regulation.

Part Three: Economics

In Part Two: Economics, Foucault turns his attention to how the ancient Greeks conceptualized sexual relations within the framework of household management, or oikonomia—the root of the word “economy.” This “economy” of pleasures was not about financial management but about the ethical and hierarchical organization of personal conduct, particularly within the family unit.

Foucault shows that sexual behavior was intricately linked to the structure and control of the household, where the male head was expected to maintain order, discipline, and self-mastery over all dependents—wife, children, and slaves. This required a specific form of ethical behavior from the man, including the regulation of his own desires to preserve his authority and maintain household harmony.

Sexual conduct, therefore, was not viewed as an isolated moral issue but as a component of governing oneself and others. A man’s ethical value was assessed in part by how well he balanced sexual activity with rational self-control and social duty. Excessive indulgence or domination through pleasure risked undermining his authority and the integrity of the household.

Importantly, Foucault argues that the morality of sexual acts was less about the acts themselves than about who performed them, with whom, and under what conditions. The focus was on status, power, and the proper exercise of authority. For example, sexual relations with slaves or young boys were acceptable under certain ethical codes, provided they did not reflect weakness or a lack of moderation.

This part also shows that the regulation of sexuality was not imposed from above through laws or religion but internalized as part of a broader ethical way of life, rooted in concepts of honor, masculinity, and civic responsibility.

Part Four: Erotics

In Part Three: Erotics, Foucault explores the Greek concept of pederasty, a socially sanctioned relationship between an older man and a younger boy, usually framed as both educational and erotic. This practice, controversial by modern standards, was deeply embedded in the ethical and pedagogical systems of ancient Greek society.

Foucault emphasizes that the central concern in these relationships was not the erotic act itself, but the moral and emotional dynamics between the two participants. The older man (erastes) was expected to display self-control, respect, and ethical restraint, while the younger boy (eromenos) was expected to maintain modesty and avoid passivity or shame. The aim was not just pleasure, but the formation of character and the development of virtue.

This ethical framework turned the act of loving another male into a training ground for moral subjectivity. The relationship was supposed to elevate both individuals, especially the younger partner, by cultivating wisdom, courage, and temperance. Foucault notes that excessive pursuit of boys or displays of lust were criticized, not because of the sex itself, but because they demonstrated a failure in ethical self-discipline.

Here, Foucault reiterates one of his core themes: in ancient thought, sexuality was an area of aesthetic and ethical self-fashioning, not just behavior to be regulated or pathologized. The central concern was how to live well, with sexuality as one dimension of ethical self-formation.

Part Five: “True Love” – Main Points, Themes, and Arguments

In Part Five: “True Love”, Michel Foucault examines the ancient Greek conception of eros (erotic love), particularly in the context of male-male relationships, mentorship, and ethical self-formation. This chapter is central to Foucault’s project of understanding how sexuality has historically been problematized, not merely as behavior but as a moral and philosophical issue. His primary concern is not to chart sexual practices themselves but to explore how individuals in antiquity were taught to relate to pleasure and desire.

A major theme in this section is the contrast between “true love” and pleasure-driven desire. Foucault explores how ancient Greek culture viewed love not simply as the pursuit of gratification but as an educational and ethical relationship—especially between older men (erastes) and younger boys (eromenos). These relationships were structured around a complex social code designed to cultivate virtue, moderation, and self-mastery. The “true” love was not just erotic but also pedagogical: it was expected to elevate the soul of the beloved and refine the character of the lover.

Foucault discusses how moderation (sōphrosynē) was an essential ethical value. The true lover was someone who demonstrated control over his desires, thereby aligning himself with the philosophical ideal of self-governance. Excessive lust or uncontrolled passion was seen as a failure of reason and ethics. In this way, erotic relationships became a field for the exercise of power over the self—a training ground for shaping one’s soul.

Importantly, Foucault highlights that the discourse on love in classical antiquity was less about prohibiting certain acts and more about guiding individuals toward ideal forms of conduct. This aligns with his broader theory of ancient ethics, where moral systems emphasized aesthetics of existence—the idea that individuals should live beautiful, balanced, and virtuous lives through active self-stylization.

The concept of “true love” also ties into Foucault’s notion of technologies of the self—practices by which individuals shape their bodies, thoughts, and behaviors in pursuit of moral or philosophical ideals. In ancient Greece, love was not just an emotional state but a relationship embedded in rituals, dialogues, and exercises aimed at producing ethical subjects.

Foucault contrasts this with modern understandings of sexuality, where identity categories (e.g., homosexual, heterosexual) dominate. In antiquity, sexual behavior was not treated as a marker of identity but as an ethical problem linked to moderation, status, and proper conduct. Thus, “true love” in this context wasn’t about discovering who one is, but about becoming a certain kind of person through deliberate ethical cultivation.

In sum, Part Five contributes significantly to Foucault’s thesis that the history of sexuality is a history of how individuals are invited—or required—to work on themselves through various forms of moral reasoning and social practice. The chapter on “True Love” reveals how erotic relationships, far from being hidden or taboo, were central to ancient philosophical inquiries about virtue, self-control, and the good life.

A Shift in Focus: From Repression to Ethics

Right from the opening pages, Foucault makes it clear that the central concern of this book is not power or discourse alone, but the ethical substance of human conduct—how ancient individuals shaped themselves into moral subjects. He writes:

“My objective, instead, was to learn why sexual behavior was more and more frequently considered to be an object of moral concern, why it was an issue, and how it was problematized…” (Foucault, p. 10)

This “problematization” of sexual behavior in antiquity forms the heart of Volume 2. In a decisive methodological pivot, Foucault presents sexuality not as a domain of repression, but as a site of self-practice, where subjectivity was constructed through philosophical reflection, medical texts, and social customs.

Structure and Content Overview

Foucault divides The Use of Pleasure into four major thematic chapters, each contributing to a fuller picture of how the Greeks conceived of and regulated sexual pleasures (aphrodisia). The organization is thematic rather than chronological, reflecting Foucault’s broader interest in concepts rather than linear narratives.

1. The Moral Problematization of Pleasure

The first chapter sets the tone by examining why the Greeks were so concerned with regulating sexual behavior, even though there was no religious prohibition against pleasure. Foucault is fascinated by this contradiction. He identifies a cultural preoccupation not with sin, but with self-mastery, a concept deeply embedded in Greek ethics. He observes:

“The use of pleasures was thus no less a matter of concern for men of antiquity than it has been for us—but not for the same reasons, not according to the same forms of analysis, and not in the same type of relationship with the subject.” (p. 47)

This passage illustrates one of the book’s key claims: that ethics are historical, not eternal.

2. Dietetics and the Regulation of Bodily Pleasures

In the second chapter, Foucault turns to dietetics, a philosophical-medical tradition that treated eating, drinking, and sex as part of a balanced regimen. Ancient thinkers believed that indulgence in pleasure could disrupt the harmony of the body and soul. Sex, therefore, had to be carefully controlled to preserve virtue and health.

“The domain of dietetics was not limited to food and drink; it also extended to sexual activity.” (p. 97)

The insight here is profound: pleasure was not forbidden, but it had to be measured, disciplined, and harmonized. The body was not a battleground for sin but a terrain for ethical cultivation. This stands in stark contrast to the modern Western framework, in which desire is often framed through repression and pathology.

3. Economic Management and the Household

Foucault’s third focus is on oikonomia—the management of the household and the male head’s role in regulating the sexual conduct of wives, slaves, and children. This was less about law and more about ethical propriety, status, and male virtue.

“The question was not so much to establish prohibitions as to define a manner of acting, a way of governing one’s behavior and that of others.” (p. 181)

Sexual conduct was understood within the larger frame of social order, and ethics emerged as a way to ensure balance and moderation—a term Foucault returns to often. This section helps illustrate his broader thesis: that ethics in antiquity was not grounded in universal law but in practices of self and household regulation.

4. Erotics and the Education of the Self

Perhaps the most moving and complex chapter deals with erotics, particularly between men and boys—a common feature of Greek social life. But Foucault doesn’t offer a judgmental or romanticized account. Instead, he investigates how such relationships were bound by codes of mentorship, restraint, and self-discipline.

“What was valorized was not the pleasure that the young boy could give, but the conduct of the man who took pleasure.” (p. 209)

Here, Foucault emphasizes that ethics was not about abstaining from pleasure but about moderating and mastering it. This, to me, is one of the most intellectually generous and emotionally challenging moments in the text. It makes us ask: What does it mean to truly master desire—not to extinguish it, but to shape it into a form that reflects our values?

Conclusion of the Summary

To summarize, The History of Sexuality Volume 2 presents a subtle, radical reframing of sexuality not as a repressed instinct but as a domain for ethical work and self-fashioning. Foucault’s use of historical sources, from Xenophon and Plato to medical writers like Galen, offers a textured, nuanced understanding of how the ancients approached pleasure, power, and virtue.

The argumentative structure is thematic but recursively layered: each chapter builds on the other while constantly returning to the question of subjectivity—how the self is made through ethical relations to sex. Foucault, with clinical precision and poetic restraint, invites us not to reject pleasure, but to rethink our relationship to it.

Critical Analysis

Reading The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault is less like consuming a conventional academic text and more like entering into a slow, reflective dialogue with history, ethics, and one’s own relationship to desire. While it is meticulous and methodical, it is also deeply evocative. It made me pause, often mid-paragraph, to re-examine assumptions I didn’t even know I held. This isn’t just a book; it’s an invitation to philosophical self-inquiry.

Evaluation of Content

Foucault’s core achievement in this volume is a profound shift from sexuality as repression to sexuality as ethical practice. He is no longer concerned with how institutions govern bodies from the outside, but how individuals govern themselves from within. And this is where the book shines. He doesn’t merely assert that ancient Greeks viewed sex differently—he demonstrates it through an astonishingly rigorous historical method, drawing from an extensive range of sources across philosophy, medicine, and domestic treatises.

One of the most striking aspects is his use of original ancient texts. For example, when discussing dietetics and bodily regulation, Foucault quotes:

“The sexual act, like food, is governed by a regimen that is specific to each constitution and circumstance.” (p. 104)

This line encapsulates his larger argument: pleasure, for the Greeks, was subject to ethical reason, not moral prohibition. It is through lines like this—presented without rhetorical flourish but with intellectual weight—that Foucault earns his authority. His ability to subtly reinterpret these historical moments is where his genius lies.

Does he succeed in proving his point? Resoundingly so. He doesn’t only reinterpret history; he reconfigures the very terms by which modern readers understand subjectivity, desire, and freedom. As he writes:

“It was a matter of constituting oneself as the subject of one’s own desires.” (p. 235)

That’s a sentence I underlined, highlighted, and wrote down in my journal. Because it made me realize something deeply personal: modern sexuality, framed around identity and liberation, often fails to ask how I relate to my own pleasures—not in terms of freedom, but in terms of responsibility and care.

Style and Accessibility

Now, let’s not pretend this book is an easy read. Like many of Foucault’s works, The Use of Pleasure demands your attention—and then some. His style is dense, methodical, and at times labyrinthine. But once you tune into his frequency, a kind of clarity emerges. He does not write to entertain. He writes to unsettle, to decenter, to provoke thought.

That said, this book is significantly more accessible than Volume 1. It has less jargon, and its structure—divided into clearly focused thematic chapters—makes it easier to digest. For scholars of Foucault, this volume is indispensable. But even for general readers interested in philosophy, ethics, or classical studies, it offers a uniquely introspective experience.

If I were to describe his tone, it would be this: quietly authoritative, never condescending, and always deeply curious. There is no rhetorical showboating here, just a patient unearthing of how humans have historically engaged with desire.

Themes and Relevance

One of the enduring strengths of The History of Sexuality Volume 2 is its relevance to contemporary discussions around ethics, desire, and identity. In an age obsessed with self-expression, Foucault subtly reminds us that the self is not merely expressed—it is crafted. He introduces what is perhaps one of the most underexplored concepts in our ethical lexicon: care of the self.

“Ethics is not only about rules or laws; it is about the relationship one has to oneself.” (p. 28)

This concept, rooted in ancient thought yet deeply resonant today, forces us to ask: What do we owe ourselves? What is the ethical responsibility we have in how we experience pleasure, love, and intimacy?

Moreover, Foucault’s critique remains startlingly current in our era of therapeutic culture and identity politics. While today’s frameworks often reduce sexuality to identity, Foucault explores it as a practice—one that is dynamic, contextual, and existentially charged.

From a thematic perspective, the text traverses ethics, power, history, and selfhood—and it does so with a graceful interdisciplinarity that few writers could maintain. These are not just academic themes; they are existential concerns.

Author’s Authority

It would be difficult to overstate Foucault’s authority on this subject. As a philosopher-historian, he is unparalleled in his ability to blend archival research with theoretical innovation. His reading of ancient Greek sources is not superficial; he dives deep into texts from Xenophon, Plato, Hippocrates, and others, not to summarize, but to excavate the ethical substrata beneath them.

His conceptual integrity is rigorous. He never makes a historical claim without context. He never allows his theories to float above the evidence. And he never imposes modern categories onto the past. That’s what makes this book so powerful—it respects both the difference of the past and the urgency of the present.

As a reader, I found this respect contagious. It made me want to not just understand Foucault’s argument but to live it, to think more critically and ethically about my own pleasures and practices.

Strengths and Weaknesses

As someone who reads Foucault not just for academic purposes but for personal transformation, I must say that The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault is one of the most compelling and profound philosophical works I’ve ever engaged with. It altered not just what I think about sexuality, but how I think about myself as an ethical subject. However, no book is without its imperfections. So let us look honestly at what this volume offers at its best—and where it might falter.

Strengths

1. Radical Reorientation of Sexual Ethics

Perhaps the greatest strength of The History of Sexuality Volume 2 lies in its capacity to reframe contemporary assumptions. In a time when sexuality is so often reduced to debates about identity, rights, or pathology, Foucault invites us to consider an entirely different question: How do we live ethically with our pleasures? This simple yet radical reframing has the potential to upend not just scholarship, but our daily lives.

“The idea was not to forbid or condemn pleasures, but to codify their use according to rational principles of moderation.” (p. 115)

This is not a book about guilt or liberation; it’s about responsibility, temperance, and philosophical self-stylization. For readers exhausted by binary moral frameworks, this is a breath of fresh intellectual air.

2. Historical Depth and Methodological Rigor

The depth of historical research is staggering. Foucault’s references to figures like Xenophon, Plato, and Galen are not just decorative; they are analytically central. He breathes life into these ancient voices, helping us understand how sexual ethics were woven into everyday life, public discourse, and personal conduct in the classical world.

The historical method here is subtle but powerful. He shows that sexuality is not a universal constant, but a concept historically constituted through practices, beliefs, and subject positions. That’s a profound and liberating realization.

“It is not the desire that is condemned; it is the failure to master oneself.” (p. 137)

3. Conceptual Clarity and Philosophical Insight

Though his prose can be challenging, Foucault is remarkably lucid in his concepts. The triad he uses—modes of subjectivation, ethical substance, and telos (ethical goal)—offers a rigorous yet intuitive framework for understanding ethics. It’s this kind of philosophical innovation that cements his legacy.

Moreover, concepts like care of the self, aesthetics of existence, and ethics of pleasure are not just academic ideas—they are tools for personal reflection.

4. Relevance to Modern Ethical Discussions

What stunned me most was how relevant these ancient frameworks are today. As we navigate questions about polyamory, gender fluidity, sexual autonomy, and digital intimacy, Foucault’s insistence on ethical self-reflection, moderation, and intentionality feels not archaic but visionary.

Weaknesses

1. Lack of Emotional Narrative or Lived Experience

As profound as this book is intellectually, it can feel emotionally detached. Foucault speaks of sex and desire with surgical precision, but rarely explores the lived emotional texture of erotic life—shame, love, longing, jealousy. These human dimensions are largely absent, and some readers may find this alienating or overly academic.

That omission becomes more noticeable when compared to contemporary works in queer theory, like Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick or Lauren Berlant, who bring more emotional granularity to the discussion of sexual subjectivity.

2. Cultural and Geographical Limits

Foucault focuses almost exclusively on Greek antiquity, which, while rich, is culturally narrow. There is no treatment of sexual ethics in Eastern traditions, indigenous practices, or even early Christian texts (which are saved for Volume 3). Readers looking for a cross-cultural analysis of sexuality may find this book limited in scope.

3. Philosophical Abstraction

While Foucault’s concepts are intellectually elegant, they are also philosophically abstract. Terms like “ethical substance” or “modes of subjectivation” require significant mental effort to internalize, especially for those unfamiliar with Continental philosophy.

For lay readers or newcomers to Foucault, the text can feel inaccessible, particularly without prior knowledge of Volume 1 or his broader theoretical work. Some guidance or commentary alongside the text would make it more approachable.

4. Absence of Critical Counterpoints

Foucault rarely engages directly with scholars or critics in this volume. There are no footnotes debating rival theories, no academic dialogues with other historians of sexuality. While this makes the text flow more elegantly, it also leaves it less open to contestation or revision. This monologic tone can make the arguments feel hermetic at times.

Final Thought on Strengths and Weaknesses

Despite these limitations, I would argue that the strengths of The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault far outweigh its shortcomings. It is not a complete theory of sexuality, nor does it pretend to be. Rather, it is a historical experiment in philosophical ethics—a work that dares us to look inward, to revise our practices, and to rethink what it means to live ethically.

As Foucault reminds us, ethics is not about adhering to rigid codes. It is about creating a form of life—a techne tou biou—that reflects the values we consciously choose. That, for me, is the most empowering takeaway from this brilliant, occasionally difficult, but deeply transformative book.

Conclusion

As I close this reflection on The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault, I’m left not with answers, but with better questions. What does it mean to live ethically with one’s desires? How do we move beyond repression without slipping into indulgence? And most importantly—what kind of person do I become through the ways I regulate, express, or enjoy pleasure?

These are the kinds of questions Foucault invites us to ask, not with guilt or shame, but with rigor, curiosity, and care.

Summary of Impressions

This book is a masterpiece of philosophical archaeology. In The History of Sexuality Volume 2, Foucault excavates the moral soil of antiquity to show us how the Greeks understood sexuality—not as a sin, not as an identity, but as a site for ethical self-cultivation. Through his analysis of dietetics, household governance, and male-male erotic relationships, Foucault reveals a mode of life in which pleasure was never just personal—it was always philosophical.

His writing is demanding, but not impenetrable. His arguments are abstract, yet deeply consequential. And his historical reach—though narrowly Greco-centric—is meticulous, illuminating, and always in the service of a larger ethical project.

“What matters is not so much the truth of the desire, but the ethics of the act.” (Foucault, p. 215)

That one sentence, for me, encapsulates the emotional heart of this book. We live in a world obsessed with discovering the “truth” about who we are—sexually, emotionally, politically. Foucault asks us to shift our gaze: from truth to ethics, from identity to practice, from repression to self-care.

Who Should Read This Book?

This is not a book for everyone—but it should be. For scholars in philosophy, gender studies, history, and political theory, The Use of Pleasure by Michel Foucault is foundational. It not only reframes sexuality but offers tools for analyzing subjectivity, ethics, and self-governance that extend well beyond the realm of sexual theory.

But even for the general reader—particularly those interested in personal growth, ethical living, and historical consciousness—this book offers rich, transformative insights. If you’ve ever wondered what it means to live a “good life” beyond external rules and laws, Foucault’s model of ethical subjectivation may feel like intellectual homecoming.

How It Compares to Similar Works

Foucault’s work stands apart from other theorists of sexuality like Sigmund Freud, who pathologized desire, or Judith Butler, who foregrounds performativity and identity. While Freud gave us the unconscious, and Butler the constructed self, Foucault gives us the crafted self—an ethics of existence forged through discipline, reflection, and moderation.

If you’ve read Volume 1 and were drawn to Foucault’s discussion of biopower and discourse, Volume 2 offers a new dimension: a quieter, more intimate exploration of what it means to be a subject not just of power, but of your own life.

Final Reflection

Reading The History of Sexuality Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure has not just informed me—it has changed me. It has made me more deliberate, more introspective, and more aware of the delicate, ongoing process of becoming who I am through how I live, how I love, and how I seek pleasure.

Foucault’s writing insists on responsibility without repression, care without guilt, and pleasure without chaos. In a world too often divided between puritanism and hedonism, this book offers a third path: the path of ethical self-formation.

So no, you don’t need to go back to the book after reading this article—but I hope you will. Because once you begin walking with Foucault, you don’t return the same.