Last updated on May 21st, 2025 at 01:36 pm

The name of The Name of the Rose was adopted from the twelfth-century Benedictine Bernard of Morley’s poem, Der Name der Rose, in Italian.

Bernard said everything disappears into a void and everything that departs leaves behind only their names. Umberto Eco, the author, left it all to the readers to conceptualise the basis of the name.

However, what I was able to comprehend what left their names behind are: the second book of Aristotle’s Poetics, the library with numerous manuscripts and books, and the magnificent monastery.

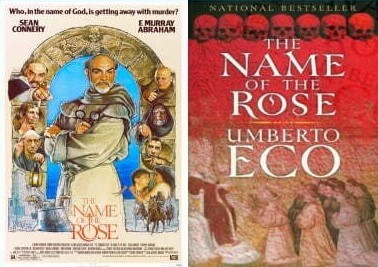

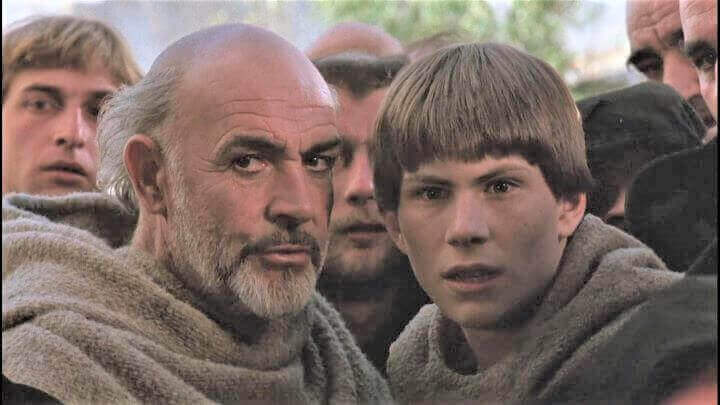

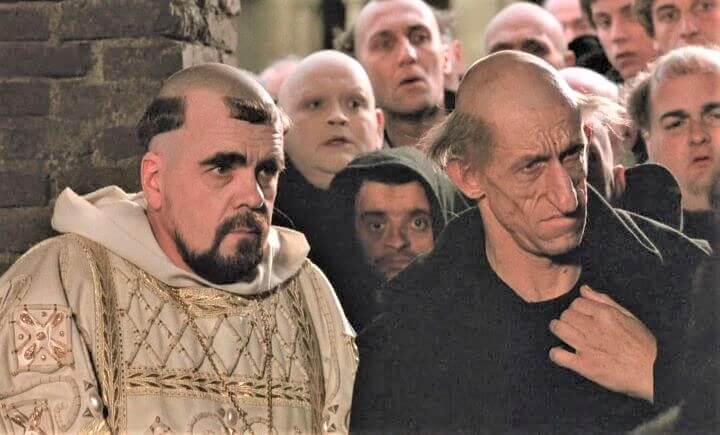

The 1986 film The Name of Rose was adopted based on the book. Acted by Sean Connery (as William of Baskerville), Christian Slater (as Adso of Melk), F. Murray Abraham ( as Bernado Gui), Volker Prechtel ( Malachia, the librarian), Helmut Qualtinger (as Remegio de Varagine), Urs Althaus (as Venantius), Michael Habeck (Berenger), Feodor Chaliapin Jr. (as Jorge de Burgos), Michel Lonsdale (as the Abbot), Ron Perlman (as Salvatore), Valentina Vargas (as the destitute girl, das Madchen) and others, The Name of the Rose 1986 is another great piece of cinematic creation.

Featured by Sean Cannery, the film portrays only a little portion of the novel which might be incoherent to many viewers as it does not reveals the details on what it was based on.

Background of The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose, originally published in Italian as Il nome della rosa in 1980, is more than a historical mystery novel. It is an intricate meditation on the nature of truth, the dangers of dogmatism, and the power of interpretation. Authored by Umberto Eco—an Italian semiotician, medievalist, and literary theorist—the novel marked his fiction debut. It was translated into English by William Weaver in 1983 and became a phenomenal international success, selling over 50 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling novels of all time.

The novel is set in the year 1327 in a remote Italian Benedictine monastery, where Brother William of Baskerville, a Franciscan friar and former inquisitor, and his young assistant, Adso of Melk, are sent to mediate a theological dispute. However, their mission quickly takes a darker turn as they are asked to investigate a series of mysterious deaths at the monastery. What follows is a profound exploration of semiotics, religious orthodoxy, and human inquiry, framed as a detective story that is as erudite as it is suspenseful.

Eco claimed in the novel’s fictional preface to have “found” the tale in a lost manuscript by Adso of Melk—an elaborate metatextual device that sets the tone for the book’s postmodern complexity. He also stated, “Let us say it is an act of love. Or, if you like, a way of ridding myself of numerous, persistent obsessions,” suggesting that The Name of the Rose was not merely an academic exercise but an emotionally charged creative undertaking.

The book weaves real historical figures—such as the inquisitor Bernard Gui and the philosopher William of Occam—into fictional events, echoing Eco’s lifelong interest in the blurred boundaries between historical fact and fictional storytelling. As a scholar of semiotics, Eco used The Name of the Rose as a vessel to dramatize how signs and symbols are interpreted, misunderstood, and weaponized.

The abbey’s labyrinthine library serves as both the symbolic and literal heart of the narrative. Hidden in its “finis Africae” room is a fictional lost volume of Aristotle’s Poetics on comedy—a book whose forbidden knowledge becomes the catalyst for multiple murders. Eco writes, “Books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told,” echoing the postmodern theory of intertextuality, which holds that no text exists in isolation.

Table of Contents

The Name Of The Rose: A Sophisticated Philosophical Masterpiece

Demanding and slow in pace I have recently been struggling with the masterpiece work by Italian philosopher Umberto Eco: The Name of the Rose.

Set in medieval 14th-century crimes that took place in a lonely Benedictine monastery in Italy, the book is a wonderful metaphysical detective novel. A work that bases it reveals some of the inevitable incidences of the time, such as the conflict between the Pope and the emperor, the cruelty of Inquisition toward heretics and the churches’ apathy toward new knowledge and obsessive guardianship toward the library.

The theological questions of whether the followers of Jesus Christ and the church must embrace poverty like Jesus Christ himself, whether laughter is allowed for his disciples, monks in that matter, papal supremacy over the people of the empire, the church perpetrated cruelty towards Franciscan followers and monks, faction between Italian and foreign monks in the abbey and how the second part of Aristotle’s Poetics had disappeared from its existence are displayed ingeniously and with linguistic brilliance.

Intrigued by style and events, I have read the book twice which took more than a month.

Italian language national daily IL Girono’s review, “A novel of stunning intelligence, linguistic richness, thematic complexity”, is unquestionably proper. The language, the style, and unity of the time are so intriguing that, one or two-time readings seemed still inadequate to me. In the postscript, Eco expressed what he expected from a reader, and he duly achieved in doing so. “I wanted to create”, writes the author, “a type of reader who, once the initiation is passed, would become my prey—or, rather, the prey of the text—would think he wanted nothing but what the text was offering him”.

The narrator, Adso, a novice Benedictine monk from Germany, accompanied William of Baskerville during his journey to another Benedictine monastery in the remote part of Italy during the early 14 century.

The novel is based on what Adso witnessed in his adolescence at the age of eighty. As a faithful chronicler of fateful events that befall one of the greatest monasteries of the Christendom, it is a memoir novel.

In its great library, the monastery procured thousands of books, commentary and valuable parchments including the only copy of Aristotle’s second book of Poetics. A monastery that never encouraged the acquisition of new knowledge except that of the biblical truth, and became the obsessive guardian of the library that prohibits comedy strictly. As misfortune have it, Poetics, which was dedicated to comedy and laughter turned out to be to focus on all the intellectually curious monk of the abbey.

Ultimately that curiosity of the monks toward the book breeds fear of sacrilege, homosexual relation, and killing instinct among themselves, the 60 monks. Jorge, a blind senior monk feared philosophy, especially of Aristotle, that it might corrupt the monks and promote atheism.

Therefore, he tried preventing monks from reaching Poetics at any cost, no matter if that comes at the cost of lives.

It portrays the middle ages’ history alongside the diabolic incidences that took place in the abbey. During their seven days of stay in the monastery, William and Adso tried to unravel the mysteries behind the sudden death of a monk while six more also followed his path including the monastery itself in the end. The incidents made look like taking place in accordance with the Book of Revelation of the New Testament.

DAY-1

William of Baskerville came to investigate Adelmo’s (a young monk who was an illuminator) death.

On their first day, they came to know about the great abbey, librarian Malachi, assistant librarian Berengar, cellarer Remegio, blind monk Jorge, illuminator Venuntius, herbalist Severinus, and glazier Nicolas, Aymaro and Salvatore etc.

Even though Adelmo’s death was thought to be occurred due to some diabolic force, William was told by the abbot that he was given a proper burial. Because he did not think Adelmo’s was a suicide or tried to conceal the fact in order to avoid suspicion of his being aware of it. William concluded that Adelmo rather committed suicide from the outer wall of the Aedificium of the abbey for a reason.

Franciscan order (a catholic religious order founded by Saint Francis), Spirituals, Fraticelli or Friar of the Poor life were discussed elaborately, on the first day. After the death of Pope Clement, who was accepted by the Franciscan Spirituals, and who fulfilled their hopes, Boniface VIII ascended the papal throne who immediately displayed an intolerance toward Franciscan Fraticelli.

After the death of Pope Clement, John XXII also was hostile towards them and determined to destroy the whole Franciscan order. John condemned the Franciscans’ idea of ‘poverty’ of ‘Christ and His apostles’ as heretical.

Because learning does not consist only of knowing what we must or we can do, but also of knowing what we could do and perhaps should not do.

Umberto Eco, The Name of The Rose

On their first day, William and Adso encountered a debate regarding comedy and laughter with the old venerable blind monk, Jorge. “Nothing in his (Jesus) parables”, reasons Jorge, “arouse laughter or fear” and laughter is a distortion of God’s image. William argues that “God can be learnt only through the most distorted things—that the more simile becomes dissimilar, the more truth is revealed to us under the guise of a horrible and indecorous figure, the less the imagination is sated in carnal enjoyment, and thus obliged to perceive the mystery hidden under the turpitude of the image”.

Jorge refuted that, ‘Christ never laughed and Son of man could laugh but it is not written that he did”. “Nothing is human nature forbade it”, William replied, “because laughter is proper to men”.

However, William could not reach the reason behind Adelmo’s suicide on the first day.

DAY-2

At down, Monday, Venuntius of Solvemec was found killed inside the jar of pig’s blood.

Nevertheless, the kill made look like a suicide. Berengar was suspected as the prospective murderer and William thinks the death, as the previous one, has a link to the library which conceals a mysterious book. The source of laughter and witticism, Aristotle’s Poetic is discussed on the second day.

Moreover, William discovered that the cellarer Berengar had developed a homosexual attraction toward young Adelmo which escalated to physical sodomy. Benno, another monk of the monastery, revealed to William that in order to satisfy Adelmo’s intellectual desire and curiosity for the mysterious book Berengar had him agreed to satisfy his carnal desire. Adelmo had the desire to get his hands on the book that he had been seeking for years by any means.

Again William engaged himself in a debate about the legality of laughter and comedy with Jorge. “Our Lord Jesus never told comedies or fables, but only clear parables which allegorically instruct us in how to win paradise”, Jorge said. In response, William wanted to know why he is so opposed to the idea that Jesus ever laughed and reasoned that laughter is good medicine like baths that treat humour and other melancholic affliction of the body.

According to Jorge, laughter shakes the body and distorts the human face and makes men similar to a monkey.

As not everything that is proper to men is not necessarily good for men, laughter makes a man disbeliever of what he laughs at. Therefore, laughing at evil things does not mean preparing oneself to combat it and laughing at good things means denying the power through which good is self-propagated. Truths and good are not to be laughed at and with his laughter a man in his heart says, Deus non-est—there is no God.

William, however, reasoned that in order to undermine an absurd proposition that offends reason, laughter is sometimes proper and it serves to confront wicked while making their foolishness evident.

William discovers the reasons behind Adelmo’s death. He, in fact, committed suicide after committing the crime of homosexual intercourse with Berengar. Felt remorse Adelmo went to confess his crime to Jorge so as to be absolved. But Jorge instead of absolving his sins imposed a harsher penance and severely reprimanded him. Deserted and helpless the poor monk threw himself off the wall.

Nevertheless, he confided the same secret about the mysterious book Berengar bartered him to another monk, Venuntius. Which he was also very much curious about. Shockingly, Venuntius was found dead the next morning. The cause of the dead is unknown, yet.

DAY-3

Among many events that took place on the third day, William cleared about the many heresies in the church to Adso.

In an attempt to explain heresies, William said, “Imagine a river, wide and majestic, which flows from miles and miles between strong embankments, where the land is firm. At a certain point, out of weariness, because its flow has taken up too much time and too much space because it is approaching the sea, which annihilates all river in itself, no longer knows what it is, loses its identity.

It’s become its own delta. A major branch may remain, but many break off from it in every direction, and some flow together again, into one another, and you can’t tell what begets what, and sometimes you can’t tell what is still river and already sea…”

Adso broke the vow of chastity by having intercourse with a village girl of sixteen in the darkness of the night. He united physically with the girl by breaking his monkish commitment.

The girl, as usual, came that night to sell her beauty to Salvatore and cellarer Remegio in exchange for some food.

Librarian Berengar was discovered drowned in the balneary bathtub.

DAY-4

Severinus, the herbalist, learned that the two dead men, Venuntius and Berengar, both have blackened fingers of right hand blackened tongue.

Cellarer Remegio and Salvatore confessed their heretical past while they went on raging against the rich. And Salvatore was apprehended for attempting black magic for the girl he loved, now a beloved of Adso, while both of them were caught by archers of Pop’s legation in the middle of the night with a black cat and a back rooster.

The Franciscan legation of Michael of Cesena, Brother Hugh of Newcastle, Bishop of Kaffa, Berengar Talloni and Bonagratia of Bergamo arrived, while on the same day also arrived the papal legation from Avignon, France. The two legations came to the Benedictine monastery so the faction between Emperor Luis of Bavarian and Pop John XXII can be solved along with the dispute regarding ‘The Poverty of Christ’. Declared heretical the Pop stood against the Franciscan order and the Emperor while the Emperor against the Pop and Franciscans sided with the Emperor.

There in the triangular conflict, the Benedictine abbot stood as a mediator to solve it.

Benedictine abbots agreed to side with Spiritual Franciscans in order to protect them from over empowering action of the Pop.

DAY-5

A debate on ‘Poverty of Christ’ and his disciples took place between the two legations in a view to solve the dispute between the Pop and Franciscan order.

Primarily, Saint Umbertino said that being the prelates of the New Testament Christ and his apostles were in a double condition. In this respect, they possessed wealth to give to the poor and to the ministers of the Church.

Secondarily, being the perfect despisers they must be considered as individual persons. In this state of affairs having civil and worldly possession is suggested, therefore, defending one’s own possession in a civil and worldly sense against he who takes it by appealing to the imperial judge.

But to think that Christ and the apostles owned possession in this sense is heretical because the Book of Matthew suggests that, “If anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, let him have your coat also”, while Christ himself dismisses all the power and lordship teaching the same thing the apostles. On the other hand, the temporal things can be possessed for the purpose of brotherly charity and this way Christ and his disciples possessed some goods natural rights, to sustain nature.

Umbertino’s opponent from the papal legation, Jean d’Anneaux said that ‘While a simple right of use of perishable goods such as bread and foods neither be considered nor be true use be suggested, but only abuse is to be considered.

Everything that believers had in common in the ancient church, held on the basis of the same ownership they had before their conversion after the descent of the Holy Spirit possessed farms in Judea and the vow to living without property does not extend to what a man needs in order to live, and when Peter said he had left everything he did not mean he had renounced property; Adam had ownership and property of things; the servant who receives money from his master certainly does not just make use or abuse of it…

Herbalist Severinus was killed in his infirmary by librarian Malachi, but cellarer Remegio was caught in the scene of occurrence as a suspect, instead. Malachi killed Severinu because he thought he stole his lover Berengar and in return, Berengar gave that mysterious book of Aristotle to him.

In fact, driven by curiosity Berengar, after the death of Adelmo and Venuntius, brought the book in the infirmary away from people’s sight to read in seclusion.

Jorge, the key mastermind for all deaths, who did not expect anyone to read the book, informed Malachi that Severinus was talking about a strange book in his laboratory to William.

On the other hand, Remegio became an easy suspect of killing because he reached the scene just after the fateful event looking for the letters he was hiding in the monastery for many years. Remegio, a former heretic and who was with the heresy of Fra Dolcino bringing destruction and killing the opponents, had been carrying the letters written by Dolcino to be delivered to his followers later.

As misfortune take it, Remegio thought Severinus talked to William about his letters, therefore, desperate he was looking for them in the laboratory while the archers of papal legation reached and caught his rummaging something among Severinus’ book-selves creating havoc.

DAY-6

The oldest of the monks revealed to William about internal faction between Italian and foreign monks.

And Malachi was not an Italian while the abbot of the monastery became abbot, not by convention but appointed on the basis of special privilege. Therefore, when Malachi dies during the mass, suspicion rose regarding Italian monks being involved with the killings. Nevertheless, a trace of the same black substance on Severinus’ fingers and tongue was found.

On the sixth day William and Adso were able to enter finally the room of Finis Africae, in the labyrinthine library where along with Aristotle’s Second Book of Poetics, other books of comedy were hidden.

Unlike the film where we see the accused are burned at stake in the abbey while William and Adso were seen leaving, the book version The Name of the Rose tells that they were taken to Avignon to present before the papal court.

During the Inquisition, inquisitor Bernard Gui, a papal delegate, did not ask and look for any evidence in order to probe Remegion’s involvement in killing Severinus. Because he had already found what he was looking for: heretics, not real killers. Who killed Severinus did not matter much while Gui was able to elicit Remegio’s heretical fast as if being heretic at the time was more of a criminal act than being a killer.

Without investigating for the real criminals, Bernard Gui found Remegio a scapegoat for his intolerance toward Franciscans.

They left the abbey with Salvatore, the little girl and Remegio on the sixth day while the justice for the four souls remained unsought for.

DAY-7

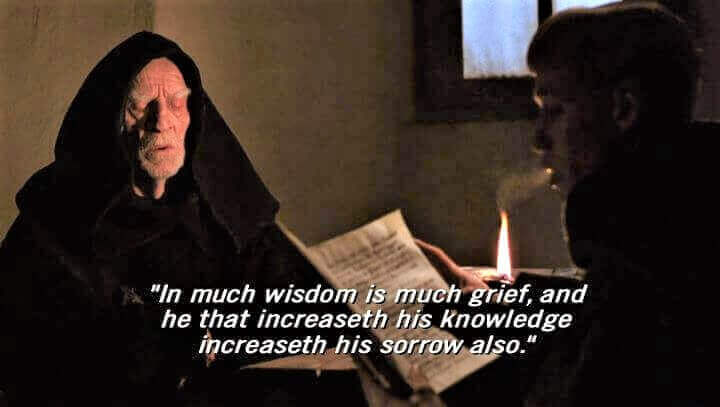

Jorge shows reasons why he had been the key to all deaths and how he accomplished it.

On the seventh day happened all the fateful and sought after incidences in the history of Christendom: Jorge killed the abbot; William and Adso finally entered the Finis Africae and were awaited by Jorge inside it at night; the mysterious book of Aristotle came to William’s hand for a brief moment; Jorge poisoned himself and the great monastery, along with the second book of Poetics, caught fire and turned into ashes.

Earlier the day before, when William expressed his concerns regarding the horrible incidences to the abbot that ‘the illicit relationship between the monks is not the key reason behind the deaths of fateful monks. Everything turns on the theft and possession of a book which was concealed in the Finis Africae”.

Raged with anger abbot did not buy William’s suspicions regarding the recent ghastly events. For the reasons behind his reluctance to accept his discovery, William formulates a few hypotheses-

First: the abbot knew everything already and imagined William would be able to discover nothing.

Second: the abbot never suspected anything, anyhow, he went on thinking it was all because of a quarrel between sodomite monks.

Third, however, William has opened his eyes, he has suddenly understood something terrible, has thought of a name and has a precise idea about who is responsible for the crimes. But at this point, he wants to resolve the matter by himself and wants to be rid of William, in order to save the honour of the abbey. Or perhaps he did not want to risk the honour of the monastery.

During the night of the seventh day, blind Jorge took position inside the Finis Africae to kill the abbot and everyone who goes after the mysterious book. Jorge was able to kill the abbot by blocking the entrance mechanism controlled from inside Finis Africae. Trapped, suffocated abbot died inside the passage.

Asked why he killed abbot Jorge said, “thanks to you he had discovered everything. He did not yet know what I had been trying to protect—he has never precisely understood the treasures and the ends of the library. He asked me to explain what he did not know. He wanted the Finis Africae to be opened. The Italians had asked him to put an end to what they call the mystery kept alive by me and my predecessors. They are driven by the lust for new things”.

William asked Jorge to show him the Greek copy written on linen paper, the book he stole and read and kept others from reading it, the book he hid cleverly and made sure no one touches it. William precisely urged him that he wanted to see the second book of Aristotle, the book everyone has believed lost or never written, and of which perhaps he had the only copy: Poetics.

Put on the gloves William started to open the old volume the old monk passed to him and asked him to read, as well. The Poetics begins:

“In the first book we dealt with tragedy and saw how, by arousing pity and fear, it produces catharsis, the purification of those feelings. As we promised, we will now deal with comedy (as well as with satire and mime) and see how, in inspiring the pleasure of the ridiculous, it arrives at the purification of that passion. That such passion is most worthy of consideration we have already said in the book on the soul, inasmuch as—alone among the animals—man is capable of laughter. We will then define the type of actions of which comedy is the mimesis, then we will examine the means by which comedy excites laughter, and these means are actions and speech”. (Abridged)

The Name of The Rose, book.

The existence of a kind of sticky substance was found stuck among the pages as William proceeds further leafing pages. It was a poisonous ointment, capable of killing anyone touches through penetrating the skin, that Jorge stole from Severinu’s laboratory a long time ago and now used on the book to prevent the curious mind from reading it. He set the trap when he noticed Venuntius showing interest in the subject of laughter, and Berengar tried to impress Adelmo by showing the book.

William tried to summarise what Aristotle said about comedy and laughter: Comedy is born from the komai—that is, from the peasant villages—as a joyous celebration after a meal or a feast. Comedy does not tell of famous and powerful men, but of base and ridiculous creatures, though not wicked; and it does not end with the death of the protagonists.

It achieves the effect of the ridiculous by showing the defects and vices of ordinary men.

Here Aristotle sees the tendency to laughter as a force for good, which can also have an instructive value: through witty riddles and unexpected metaphors, though it tells us things differently from the way they are as if it were lying, it actually obliges us to examine them more closely, and it makes us say: Ah, this is just how things are, and I didn’t know it. Truth is reached by depicting men and the world as worse than they are or than we believe them to be, worse in any case than the epics, the tragedies, lives of the saints have shown them to us.

Asked why he wanted to hide, while there are other books on comedy, this particular book, Jorge said because it was by the Philosopher. Every book by that man has destroyed a part of learning that Christianity accumulated over the centuries. Every word of him had overturned the image of God. If this book were to become an open object of interpretation we would have crossed the last boundary.

Jorge feared that laughter has elevated into an art, and the doors of the world of the learned are open to it while it has become an object of philosophy.

The old blind monk thought the book is a cursed one and must not let it be read. Taking away the book from William he started tearing the pages of the manuscript and stuffing them into his mouth as if they were bread. The poisonous substance caused him to spill the yellowish slimy substance from his mouth. He began the journey of eating up Aristotle page by page!

Faced with a violent objection to his ignoble indigestion process by William, Jorge threw the volume toward Adso, who was holding the lamp, making it flung away from his hand while at the same time spilling oil on the hip of the old books and manuscripts. Immediately the pile of books is seized by the fire from the lamp and burned like a hip of dry twigs.

In a moment the whole room of Finis Africae was on fire while Jorge disappeared in the darkness of the Aedificium after he successfully throwing the book in the middle of the incineration, which was already had gone beyond control. At the death of night, gradually, the whole library and entire Aedificium was engulfed by the blazing fire.

Due to inaccessibility to the complex labyrinth monks and servants who tried to extinguish the fire abruptly failed. The poisonous substance that already took Jorge and makes him collapsed somewhere inside the labyrinth, and had turned into ashes with the magnificent structure of time that stood for centuries in Italy with Benedictine glory. It took three days to transform itself into dust.

After that, William and Adso went back to Munich and after that Adso returned to Melk while the fate of William remained unknown after their path departed. Adso, after many years, learnt that William died in Europe during a plague that spread through the continent in the middle of the fourteenth century. Luis the Bavarian sentenced John XXII to death as a heretic.

After a few years, Adso visited the burnt site of the monastery and collected fragments and remains and made a small library form them.

Reception and Criticism of The Name of the Rose

Critical Acclaim

Upon its release, The Name of the Rose was met with widespread acclaim from critics, scholars, and general readers alike. It won the Strega Prize in 1981 and the Prix Médicis Étranger in 1982, cementing Eco’s reputation as a novelist of intellectual brilliance and narrative boldness. Reviewers lauded the novel’s ability to combine medieval scholarship with detective fiction. Many called it “a novel of ideas” masquerading as a whodunit.

As Patricia McManus notes in the Encyclopædia Britannica, “Eco’s work gives the reader both a clear defense of semiotics and an intricate detective story.” She adds that the novel asks its readers to “respect the polyphony of signs, to slow down before deciding upon meaning, and to doubt anything that promises an end to the pursuit of meaning”. In other words, the novel is a celebration of interpretive labor—the human struggle to decipher truth from conflicting signs.

Literary scholars were particularly captivated by how The Name of the Rose bridged genres: it is simultaneously a mystery, a philosophical dialogue, and a postmodern critique of absolute truths. Critics praised Eco’s daring use of Latin, theological discourse, and medieval historical detail—features that would have been daunting in a less capable narrative.

Intellectual Criticism

However, The Name of the Rose was not without its detractors. Some critics accused Eco of sacrificing emotional depth for intellectual ornamentation. The novel’s tendency to interrupt the murder mystery with long philosophical digressions on Aristotle, laughter, or heresy left some readers overwhelmed. Others felt the book occasionally veered into academic self-indulgence.

A few reviewers also found the pacing uneven, particularly during the long expository sections. As Jorge of Burgos—the blind monk antagonist—delivers theological monologues, the narrative slows. Some critics described these scenes as more instructive than immersive. The tension between narrative propulsion and theoretical density became a frequent point of contention.

More pointedly, feminist critics have called attention to the almost total absence of developed female characters. The only major female figure—a nameless peasant girl—is reduced to a silent object of Adso’s fleeting sexual curiosity. Her voicelessness and erasure from the narrative have drawn criticism for reinforcing patriarchal tropes embedded in both medieval and modern literature.

Others, particularly theologians, found Eco’s portrayal of the medieval Church overly cynical. The book’s depiction of monastic corruption, violent inquisitions, and theological rigidity was seen by some as anachronistic, shaped more by modern skepticism than accurate historiography.

Cultural Legacy

Despite these criticisms, The Name of the Rose remains one of the most culturally resonant novels of the late 20th century. It was adapted into a successful 1986 film starring Sean Connery as William of Baskerville and Christian Slater as Adso of Melk. The movie, while streamlining the philosophical density of the text, introduced Eco’s work to a broader international audience.

The novel has also been interpreted across various academic disciplines—from theology and medieval studies to literary theory and media semiotics. Its central symbol, the lost book of Aristotle’s Poetics on Comedy, has become a philosophical cipher in itself: a metaphor for suppressed laughter, censored knowledge, and the tension between reason and repression.

Themes and Postmodern Structure of The Name of the Rose

The Name of the Rose is not just a historical mystery novel set in a 14th-century monastery. It is a rich, polyphonic narrative layered with theological disputes, philosophical meditations, and semiotic puzzles. While the surface narrative follows a classic whodunit structure, beneath that lies a labyrinth of meaning—appropriately mirrored by the book’s central architectural symbol: the monastery library, itself a literal and metaphorical maze.

The Search for Truth in a Fragmented World

At its core, The Name of the Rose is an extended meditation on the limits of knowledge and interpretation. Brother William of Baskerville functions not only as a Sherlock Holmes-style investigator but as a symbol of rational inquiry in a world governed by fear, superstition, and orthodoxy. Throughout the novel, he repeatedly warns against overconfidence in human reason:

“The order that our mind imagines is like a net, or like a ladder, built to attain something.”

This idea—of provisional knowledge and interpretive uncertainty—is central to Eco’s semiotic philosophy. The signs around us are unstable. They point in multiple directions. They resist closure. The Name of the Rose, therefore, becomes a parable of the modern reader’s own predicament: forever searching for meaning in a world where meaning is unstable, elusive, and contested.

Eco himself noted that “the universe is not a dictionary but a library”—a place of overlapping, contradictory texts, some missing, some unreadable, some censored. The burned books at the novel’s climax do not just represent lost knowledge; they dramatize the fragility of interpretation in a world eager to control and suppress meaning.

The Power and Peril of Laughter

One of the most memorable and unique themes of The Name of the Rose is its philosophical engagement with laughter. The forbidden book at the heart of the murders—a lost volume of Aristotle’s Poetics discussing comedy—is viewed as dangerously subversive by Jorge of Burgos, the blind librarian and secret antagonist.

To Jorge, laughter is corrosive. It undermines faith. It mocks authority. He believes, “Laughter kills fear, and without fear there can be no faith.” By contrast, William sees laughter as essential to human sanity—a sign of intellectual openness and moral humility.

This dichotomy between authoritarian repression and intellectual curiosity reflects broader medieval tensions between faith and reason. Jorge embodies the rigidity of dogma; William, the spirit of inquiry. The burning of the library becomes more than a literal fire: it is an allegory for ideological censorship, for the silencing of laughter, pluralism, and dissent.

Postmodern Narrative Play

As a master of postmodern fiction, Umberto Eco does not just tell a story; he draws attention to the act of storytelling itself. The novel begins with a pseudo-scholarly preface, in which Eco frames the text as a recovered manuscript translated and commented upon by an anonymous editor. This metafictional device introduces the idea that truth is always mediated—filtered through layers of perspective, language, and interpretation.

Adso of Melk, the narrator, admits in the very first chapter that he no longer remembers the girl he loved—not her name, not even her face. This narrative lapse gives the novel its title: The Name of the Rose. The rose—beautiful, symbolic, yet ephemeral—becomes a metaphor for lost meanings, forgotten loves, and the ultimate impossibility of fixing any truth permanently in language.

As Eco explains in the Postscript to The Name of the Rose, “The rose is a symbolic figure so rich in meanings that by now it hardly has any meaning left.” In other words, the title itself is a semiotic riddle: it draws attention to the emptying out of signs in a postmodern world.

The Library as Labyrinth

Few symbols in modern literature are as haunting as the library in The Name of the Rose. Modeled after Jorge Luis Borges‘s famous story “The Library of Babel,” Eco’s library is a physical maze where knowledge is stored—and hoarded—by monks who fear its liberating power.

The finis Africae, the forbidden chamber at the heart of the library, holds the secret that the monks would kill to protect. But the true horror of the novel is that this knowledge is not demonic or heretical—it is simply a text about laughter. The panic stems not from evil content, but from the possibility of interpretive freedom.

The labyrinth, then, is not just architectural. It is a symbol of epistemological entrapment. Every corridor is a text. Every turn, a new meaning. William’s desperate race through the flames is a desperate race through centuries of forbidden knowledge, a futile attempt to rescue what centuries of dogma had buried.

The Philosophical Legacy of The Name of the Rose

A Global Intellectual Phenomenon

The Name of the Rose became a global literary phenomenon, translated into over 40 languages, adapted into film and television, and studied in universities across the world. Its legacy endures not because it tells a gripping medieval murder mystery—though it certainly does—but because it dramatizes the existential tensions at the heart of modern life.

For readers in the postmodern age—caught between too many meanings and not enough clarity—Eco offered both a warning and a refuge. He warned us about authoritarianism, but also about intellectual arrogance. He reminded us that laughter, doubt, and curiosity are all tools of liberation.

The Name Of The Rose Quotes

“The beauty of the cosmos derives not only from unity in variety but also from a variety in unity.”

“Inquisitors often, to demonstrate their zeal, wrest a confession from the accused at all costs, thinking that the only good inquisitor is one who concludes the trial by finding a scapegoat…”

“Because of mankind’s sins, the world is teetering on the brink of the abyss, permeated by the very abyss that the abyss invokes.”

“Bevagna seduced nuns, telling them hell does not exist, that carnal desires can be satisfied without offending God, that the body of Christ (Lord, forgive me!) can be received after a man has lain with a nun, that the Magdalen found more favour in the Lord’s sight than the virgin Agnes, that what the vulgar call the Devil is God Himself because the Devil is knowledge and God is by definition knowledge!..”

“You mean that between desiring good and desiring evil there is a brief step because it is always a matter of directing the will.”

Those whom you cannot love you should, rather, fear.”

William of Baskerville, The Name of The Rose-1986

“..it is only petty men who seem normal….hell is heaven seen from the other side.”

For three things concur in creating beauty: first of all integrity or perfection, and for this reason, we consider ugly all incomplete things; then proper proportion or consonance; and finally clarity and light, and in fact, we call beautiful those things of definite colour. And since the sight of the beautiful implies peace, and since our appetite is calmed similarly by peacefulness, by the good, and by the beautiful, I felt filled with great consolation and I thought how pleasant it must be to work in that place.

“One should not multiply explanations and causes unless it is strictly necessary.”

“Laughter is something very close to death and to the corruption of the body.”

“Because learning does not consist only of knowing what we must or we can do, but also of knowing what we could do and perhaps should not do.”

“The abbot looked at him with uneasy amazement, as if to signify that he was struck to see my master harbour a suspicion that he himself had briefly harboured, for more comprehensible reasons.”

“It matters a great deal because here we are trying to understand what has happened among men who live among books, with books, from books, and so their words on books are also important.”

“Aristotle had dedicated the second book of the Poetics specifically to laughter, and that if a philosopher of such greatness had devoted a whole book to laughter, then laughter must be important…Aristotle had spoken of laughter as something good and an instrument of truth.”

“Do not seal my lips by opening yours.”

Here someone does not want the monks to decide for themselves where to go, what to do, and what to read. And the powers of hell are employed, or the powers of the necromancers, friends of hell, to derange the minds of the curious. …”

“Kill them all, God will recognise His own.”

William of Baskerville, The Name of The Rose-1986

“Have you found any places where God would have felt at home?”

For daytime sleep is like the sin of the flesh: the more you have the more you want, and yet you feel unhappy,…sated and unsated at the same time

“Men are animals but rational, and the property of man is the capacity for laughing.” “What makes them live is also what makes them die.”

“As the doctors have said beautiful also are the breasts, which protrude slightly, only faintly tumescent, and do not swell licentiously, suppressed but not depressed.”

“A monk who practices poverty sets a bad example for the populace, for then they cannot accept monks who do not practice it.”

“For a truth that dwells in me, which I can proclaim only by death.”

“Truth is indivisible, it shines with its own transparency and does not allow itself to be diminished by our interests or our shame.”

“Sons, when mad love comes, man is powerless!”

“And in carnival time everything is done backwards. As you grow old, you grow not wise but greedy.”

“We know things better through love than through knowledge.”

“Books speak of books: it is as if they spoke among themselves.”

“Books are not made to be believed but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means, a precept that the commentators of the holy books had very clearly in mind. The unicorn, as these books speak of him, embodies a moral truth, or allegorical, or analogical, but one that remains true, as the idea that chastity is a noble virtue remains true.”

“Love as an assiduous thought of a melancholy nature, born as a result of one’s thinking again and again of the features, gestures, or behaviour of a person of the opposite sex: it does not originate as an illness but is transformed into illness when, remaining unsatisfied, it becomes obsessive.”

“The beauty of the body stops at the skin. If men could see what is beneath the skin, they would shudder at the sight of a woman.”

“Here we are not talking about the truth that makes us free, but about excessive freedom that wants to set itself up as truth!”

“Bernard is interested, not in discovering the guilty, but in burning the accused.” “His is a distorted lust for justice that becomes identified with a lust for power.”

“When a man has little time, he must take care to maintain his calm. We must act as if we had eternity before us.”

“But the law is imposed by fear, whose true name is fear of God.”

“The Antichrist can be born from piety itself, from excessive love of God or of the truth, as the heretic is born from the saint and the possessed from the seer.”

Jorge feared the second book of Aristotle because it perhaps really did teach how to distort the face of every truth so that we would not become slaves of our ghosts. Perhaps the mission of those who love mankind is to make people laugh at the truth, to make the truth laugh because the only truth lies in learning to free ourselves from insane passion for the truth.

The Name of the Rose in Comparison

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco is a novel that defies easy classification. It has been labeled everything from a historical mystery novel to a semiotic labyrinth, from a monastic detective story to a philosophical allegory. To better appreciate its brilliance, it’s worth comparing it with other works—both classic and contemporary—that echo its themes, structure, or intellectual ambitions.

Holmesian Echoes: Detective Fiction and The Name of the Rose

The most immediate point of comparison is, of course, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. Eco does not hide this influence. His protagonist, William of Baskerville, is named in direct reference to The Hound of the Baskervilles. William shares Holmes’s piercing logic, empirical mind, and idiosyncratic charisma. His sidekick, Adso of Melk, is clearly modeled after Dr. Watson, serving as both a chronicler and emotional counterweight to the rational detective.

But while Doyle’s Holmes stories celebrate the detective’s near-omniscient mastery of evidence and deduction, Eco’s version is deliberately fallible. William’s conclusions are tentative. He is frequently wrong. He admits:

“I have never doubted the truth of signs… only the system of their interpretation.”

Here lies a critical divergence: The Name of the Rose is detective fiction turned on itself, where the mystery isn’t just who committed the murder, but whether the truth can ever be fully known. While Sherlock Holmes solves puzzles, William of Baskerville disassembles them—and leaves the reader with philosophical shards.

Historical Fiction: Hilary Mantel, Robert Bolt, and Eco

Eco’s meticulous reconstruction of the 14th century puts The Name of the Rose in conversation with other landmark works of historical fiction. One might think of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, which similarly immerses the reader in theological and political complexities of a bygone era. Like Mantel, Eco does not romanticize the past—he renders it intellectually vibrant but spiritually conflicted.

Whereas Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell navigates Reformation England with Machiavellian pragmatism, Eco’s William of Baskerville moves through a decaying Catholic Europe, caught between scholasticism and mysticism. In both cases, historical fiction becomes a mirror for contemporary anxieties about authority, belief, and identity.

Eco’s monastic world can also be compared with Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, which dramatizes the trial of Thomas More. Both works depict ecclesiastical figures caught between institutional loyalty and personal conscience. But Eco adds another layer: the corruptive power of knowledge control. The library in The Name of the Rose is a more terrifying instrument of suppression than any inquisitor’s rack.

Postmodernism: Borges, Calvino, and the Labyrinth of Meaning

When critics speak of The Name of the Rose as a postmodern masterpiece, they often compare it to Jorge Luis Borges, and rightly so. Borges’s story “The Library of Babel” is the clear inspiration for Eco’s labyrinthine library—a place where endless books point toward endless interpretations, none of them final.

Like Borges, Eco plays with intertextuality, metafiction, and philosophical abstraction. But unlike Borges’s icy brevity, Eco’s novel is baroque, sensual, and emotionally textured. Where Borges sketches intellectual paradoxes, Eco paints them across a 500-page canvas.

Similarly, Italo Calvino—especially in If on a winter’s night a traveler—builds recursive, self-aware texts that reflect on their own construction. Eco does the same through Adso’s unreliability and the framing device of a “found manuscript,” inviting readers to question the authority of any narrative voice.

Postmodern fiction often dismantles linear storytelling and fixed meanings, and The Name of the Rose does this with medieval flair. It asks: What is truth? Whose truth matters? And what if every act of reading is also an act of misreading?

Religious Allegory and Dystopian Precursors

The theological undercurrents of The Name of the Rose align it with older religious allegories and dystopian critiques of doctrinal tyranny. One can see parallels with Dante’s Divine Comedy, which also explores the intersection of sin, reason, and divine justice within a highly structured cosmology.

Yet Eco’s tone is not salvific. It is tragic. He does not offer heaven but ambiguity. His worldview aligns more closely with George Orwell’s 1984, where truth is rewritten by those in power, and even language becomes a tool of domination. In the monastery, knowledge is hoarded, censored, even poisoned—literally, in the case of the deadly pages.

Jorge of Burgos, the blind librarian who destroys the Aristotle manuscript, might be read as a medieval O’Brien, Orwell’s minister of truth, who seeks to annihilate not just knowledge but the possibility of laughing at power.

Comparisons with Modern Philosophical Fiction

Another point of comparison is Albert Camus’s The Plague and Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov—both novels steeped in existential inquiry. Like Dostoevsky, Eco embeds philosophical debate within his plot, often veering into didactic dialogues on free will, heresy, and divine justice.

William of Baskerville’s rationalism might even be seen as a rejoinder to Ivan Karamazov, who challenges God’s moral order. In The Name of the Rose, the order is no longer moral or divine—it is fractured, coded, and fleeting. Truth is no longer eternal; it is circumstantial.

Pros and Cons of The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose has earned its place as a landmark in both historical and postmodern literature. But like all works of ambitious scope, it is not without its strengths and shortcomings. Below is a balanced, in-depth examination of the novel’s pros and cons—from its intellectual achievements to the criticisms that have surrounded its structure, characters, and thematic complexity.

✅ Pros of The Name of the Rose

1. Intellectual Depth and Interdisciplinary Brilliance

One of the most celebrated strengths of The Name of the Rose is its remarkable intellectual scope. The novel synthesizes theology, semiotics, literary theory, medieval history, and detective fiction in a way that is virtually unprecedented in popular literature.

Eco’s background as a scholar in semiotics enriches the narrative with deep philosophical questions about interpretation, truth, and knowledge. The murder mystery is a narrative vessel for exploring the ways human beings derive meaning from signs and texts. As William of Baskerville puts it:

“Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry.”

This quote encapsulates the novel’s core principle: intellectual humility.

2. Rich Historical Immersion

From the clothing of the monks to the architecture of the labyrinthine library, every detail in The Name of the Rose immerses the reader in 14th-century monastic life. Eco’s attention to medieval theological disputes, especially between the Franciscans and the Inquisition, adds realism and nuance. Readers walk away feeling as though they’ve lived in a Benedictine abbey—right down to the cold stone cloisters and candlelit scriptoriums.

3. Layered Mystery and Symbolism

The central murder mystery is compelling on its own, but it also functions as a philosophical allegory. The deaths, triggered by a poisoned book, represent the deadly consequences of intellectual repression. The mysterious finis Africae, the hidden chamber in the library, becomes a metaphor for forbidden knowledge and the danger of unchallenged orthodoxy.

This dual function of story and symbol keeps The Name of the Rose engaging across multiple rereadings.

4. Postmodern Structure and Literary Innovation

Eco’s use of metafictional devices—like the fictional manuscript preface and unreliable narration—shows the influence of postmodern fiction while preserving an emotional and intellectual connection with the reader. These structural choices turn the novel into a meditation on how stories are told and how truth is constructed.

5. Universal Themes with Modern Resonance

Despite its medieval setting, the novel resonates powerfully with modern readers. Its themes—censorship, authoritarianism, the weaponization of knowledge, and the search for truth—are timeless. In an age of misinformation and ideological rigidity, The Name of the Rose feels more relevant than ever.

❌ Cons of The Name of the Rose

1. Dense and Challenging for Casual Readers

One of the most common criticisms of The Name of the Rose is its density. Eco himself acknowledged that he wrote the book for “a model reader,” one capable of navigating Latin quotations, theological debates, and long philosophical digressions. For readers expecting a straightforward mystery novel, the slow pace and intellectual weight can be alienating.

Entire chapters—particularly those involving monastic councils and doctrinal disputes—may feel impenetrable to those unfamiliar with medieval history or Catholic theology.

2. Pacing Issues and Structural Imbalance

While the first act of the novel builds suspense masterfully, the middle portion can feel sluggish due to extended expository passages. The resolution, too, while climactic in a symbolic sense, is more about philosophical closure than narrative satisfaction. For genre readers expecting a tight detective arc, this structure may feel uneven.

Critics have argued that the novel often sacrifices momentum for meditation, which can dilute the emotional intensity of the mystery itself.

3. Underdeveloped Female Characters

One of the most serious critiques of The Name of the Rose is its lack of meaningful female representation. The only significant female figure is an unnamed peasant girl who exists solely as an object of desire and temptation for Adso. Her silence and erasure are thematically aligned with the novel’s motifs of lost knowledge and forbidden experience, but from a feminist literary standpoint, this absence is problematic.

Some argue that Eco missed an opportunity to enrich his philosophical inquiry by engaging with gendered power dynamics within the Church and the wider medieval world.

4. Occasional Academic Overindulgence

While many readers appreciate Eco’s erudition, others view certain passages as overly indulgent. The novel occasionally veers into what might be described as intellectual showing off—using untranslated Latin, quoting obscure theological texts, or delving into esoteric logic puzzles that don’t always advance the plot.

These moments can feel more like lectures than literature, alienating readers not steeped in academic disciplines.

5. Ambiguity in Resolution

Eco’s commitment to ambiguity—epistemological and moral—means that the ending of The Name of the Rose is deliberately inconclusive. The truth behind the murders is revealed, but it leads not to triumph, but to loss: the library burns, the girl disappears, and Adso grows old in regret.

For readers conditioned by the genre’s typical sense of justice or restoration, the emotional payoff may feel unsatisfying. But as Eco asserts, “The only truth lies in learning to free ourselves from insane passion for the truth”.

Conclusion:

With numerous historical facts regarding the religious and imperial hegemony of medieval Europe, mysteries and history born out of the religious supremacy of Catholicism, outstanding, vivid depiction and portrayal of age and nature, linguistic brilliance in forming of perception and moral quest The Name of the Rose is a book that deserves a frequent visit.

It promises to deliver to the readers the intellectual, philosophical, linguistic, investigative, and theological and beauty of literary quests.

This piece serves as any other book and film review of mine on this site. Grateful for your time and patience.