The problem The Silver Book solves: How do you live, make art, and love freely when fascism, homophobia and spectacle are all closing in on your body at once?

When I read The Silver Book by Olivia Laing, I felt it grappling with the numbness that comes from watching cruelty through screens and headlines. Set amid 1970s Italian cinema and the so-called Years of Lead, it asks what it costs to keep looking rather than turning away.

The novel pushes you to face the link between gorgeous images, political violence, and the quieter compromises you and I make every day.

For me, the book says that beauty is never neutral; it is always paid for with someone’s body, someone’s risk, someone’s silence.

Once you’ve seen that trade-off play out between Nicholas, Danilo, Fellini and Pasolini, it becomes impossible not to notice similar bargains in our own cultural and political life.

Laing braids real historical events—the production of Fellini’s Casanova, Pasolini’s Salò and the still-disputed murder of Pasolini on an Ostia beach in 1975—with archival research and criticism they’ve done on these artists, so the novel’s wildest scenes rest on a bed of fact rather than pure invention.

The Silver Book is best for readers who like historically grounded queer fiction, slow-burn noir and meta-cinematic novels, and probably not for anyone who needs tidy plots, cushioned violence or a morally uncomplicated love story.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

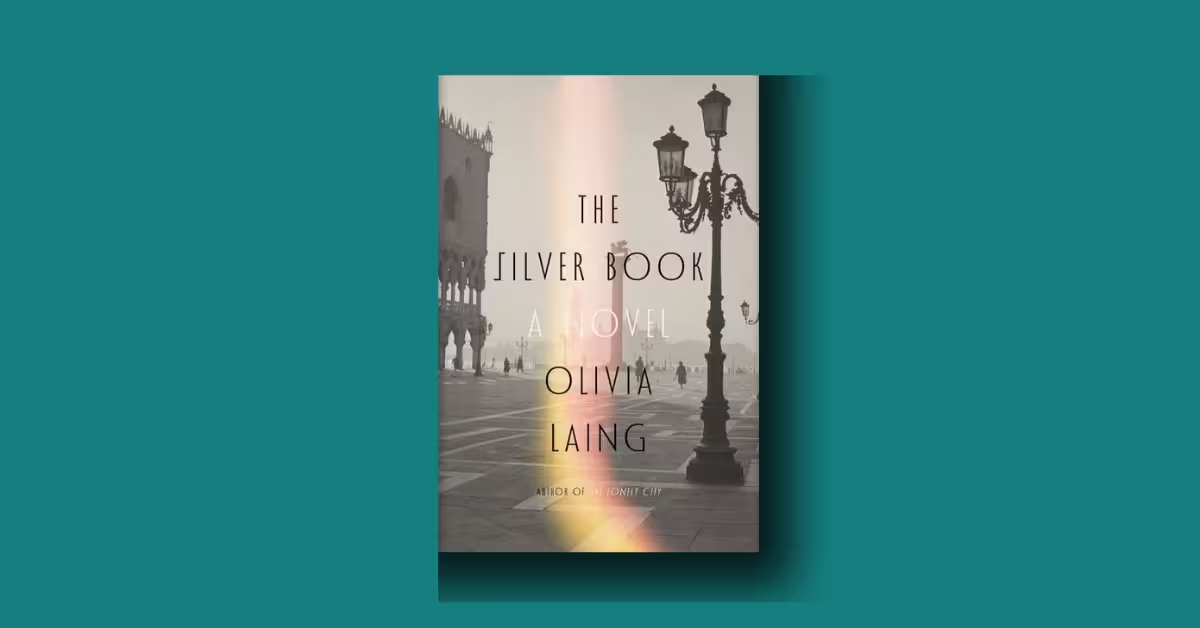

The Silver Book is Olivia Laing’s second novel, published in 2025 by Hamish Hamilton in the UK and Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US, running to about 256 pages in hardback.

Laing, better known for non-fiction like The Lonely City and Everybody, turns here to historical fiction that plays like “a novel in love with cinema”, as they themselves have described it.

The book follows Nicholas Wade, a young English artist who flees a haunted London for Venice after a vision of his dead lover, Alan.

There he falls into the orbit of real-life costume and set designer Danilo Donati, whose work underpins films by Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini.

From Venice to Rome’s Cinecittà studios and finally to the brutal coastline where Pasolini is murdered, Laing threads a queer love story through the machinery of 1970s Italian cinema and state violence.

Marketing copy calls The Silver Book both a queer love story and a noir-ish thriller, and on Goodreads, over 3,000 readers had it marked as “want to read” even before most launch events, which tracks with how buzzy the premise is.

At the same time the structure—short, cinematic scenes, written almost like shots and cuts—means you’re always aware of the difference between life and the images being manufactured around it.

By the time I closed the book, I felt I’d watched a dangerous film develop in the darkroom of history, frame by frame.

2. Background

Laing sets the novel in Italy between 1974 and 1975, the tail end of what historians call the anni di piombo, or Years of Lead—a period marked by kidnappings, bombings and ideological street wars between far right and far left.

Instead of approaching this as a conventional political thriller, the book embeds that turbulence in the working days of a film crew, starting with the baroque chaos of Fellini shooting Casanova and moving into the colder, more ascetic set of Pasolini’s Salò.

Real history anchors the story: reels were in fact stolen during the making of both films, and Pasolini really did die violently at Ostia, with conspiracy theories still swirling decades later.

Laing’s author’s note stresses that while the details of who killed Pasolini and why remain unresolved, what matters is the system he warned about—one in which we are all enmeshed, and which has only grown more powerful.

What fascinated me while reading was how much of the novel’s tactile richness comes from Laing’s research into costume houses, film logistics and Pasolini’s essays and poetry on consumerist fascism.

There’s a throwaway scene where Danilo briskly lists the absurd substitutes for snow, ice and glass on set—foodstuffs, chemicals, scraps of cloth—and it reads like a love letter to pre-digital, handmade movie magic.

All of this means the background never feels like exposition to me; it feels like being allowed to stand just off-camera, smelling the glue and sweat that make a “masterpiece” possible.

3. The Silver Book Summary

Olivia Laing’s The Silver Book follows one young man, Nicholas Wade, through a few blistering years in the mid-1970s that burn away his illusions about art, love, sex, and innocence. What begins as an impulsive escape from scandal in London becomes an immersion in the volatile worlds of Fellini and Pasolini, and ends with Nicholas confronting the life he’s built out of lies and longing.

Nicholas flees London

The novel opens in London, 1974. Twenty-two-year-old Nicholas is walking back from the Tate when a newspaper billboard stops him cold: there’s a photograph of Alan, the older married man he’s been seeing, with a headline that makes him physically sick. Alan is dead, and the tone of the headline makes it clear there’s some scandal attached. Nicholas understands at once that his own role in Alan’s life and death could come to light.

He goes straight back to Alan’s mirrored bachelor flat in Tufton Street – a place he’s always hated for the way it reflects him from every angle – and swiftly erases himself. He packs his clothes into a bag, empties a neat stack of twenty-pound notes from the bureau, leaves his books (no names in the flyleaves, nothing traceable), and decides he has to leave London immediately.

It is 17 September 1974; Nicholas registers not just the shock of Alan’s death but the sense that he has already “obliterated the first of his lives.”

At the station he buys a ticket for the Night Ferry to Paris, then on across Europe.

On the boat he can’t sleep; the air smells of vomit and diesel, but planning is a way to hold off panic. He decides not to linger in France. Instead he’ll go to Venice, a city he knows only through paintings and films – Death in Venice, Don’t Look Now – a place with a reputation as somewhere you go to dissolve or reinvent yourself.

Venice: Danilo Donati and a second life

By the time the train glides across the water into Venice, Nicholas’s terror has tipped into exhilaration. He’s slipped the net; nothing about Alan was written down, and he keeps telling himself that means he can’t really be blamed. At the same time, the “fact of Alan” hangs over him like an unassimilated object he can’t quite look at.

He takes out his sketchbook and starts drawing a small, not particularly special church in Campo Santo Stefano.

This is where Danilo Donati – the real historical costume and production designer, here turned into a major fictional character – sees him for the first time. Danilo, sulking in Venice after falling out with Fellini over their new film, notices the pale English boy with flaming red hair, hunched over his pad. He’s irritated to feel his first thought is that Fellini would love that face.

Still, he can’t quite resist. After spotting Nicholas again, he eventually approaches him, critiques his choice of subject, and testily tells him the church is better inside.

A flirtation and then a working relationship develop with surprising speed. Danilo is older – nearly fifty – mercurial, funny, and powerful. He has stories about sewing buttonholes for Callas during the war, about working with Visconti and Pasolini; Nicholas is dazzled by his mixture of camp and authority.

They wind up in Danilo’s hotel room, a “cavern under the sea” where Nicholas feels like a pearl being set. Sex comes quickly, but more important is the offer that follows: Danilo calls Fellini from a phone booth and announces that he has found an apprentice.

Over the next days Nicholas works ferociously. Danilo sends him through Venice with lists of architectural details to draw – beds, fireplaces, doorways – that he will fold into his designs for Fellini’s Casanova.

In the evenings they drink and talk; Danilo complains about having to build “Fellini’s Venice” on a soundstage rather than filming the real city, and Nicholas listens, entranced by both the practical magic of film and Danilo’s mastery of illusion: sugar for glass, feathers for snow, Parmesan cheese for ice.

By the time Danilo suggests Nicholas come back to Rome with him to work on the film, Nicholas has already stepped through what he thinks of as a revolving door into a “second life.”

He has a job, a salary he never expected, and somewhere to live – with Danilo, at least at first. When Danilo gives him a key to the Rome flat, joking that the cream-stuffed buns he’s brought home are what Roman boys offer their fiancées, Nicholas understands he’s being folded into a new, dangerous kind of family.

Rome and Cinecittà: illusion as daily life

Rome, and especially Cinecittà, is a revelation. Danilo belongs there; from the moment they pass under the CINECITTÀ sign he’s mobbed by greetings and in-jokes. Nicholas, by contrast, is the new mozzo – cabin boy, gofer, bottom of the heap. The workshop staff are suspicious of the English redhead who has clearly arrived under the boss’s wing.

Tools go missing, conversations drop when he walks in, and he has to force himself through the door every morning, smiling, asking politely where the fixative is kept.

Gradually he carves out a place. He’s quick and talented, and they begin to call him Mozzo with rough affection.

He learns the color-coded hierarchy of the studio – white coats for lab technicians, pink for equipment runners, brown for carpenters – and starts to love the backlot’s strange landscapes: kittens sleeping in a spaceship, chickens pecking under a Roman aqueduct.

Danilo’s genius is everywhere. Casanova is monstrously ambitious: fifty-plus sets, real canals and bell-towers recreated out of plaster and paint, hundreds of costumes and wigs.

Danilo is determined to make “authentic illusions,” devising cheap but spectacular solutions like replacing costly lace with a nasty synthetic fabric that, under the lights, looks extravagantly period-appropriate. He tells stories as he cooks carbonara in the workshop – of La Scala divas, Pasolini’s Arabian Nights, growing up in the war – and everyone, Nicholas included, is enthralled.

Their private life is more complicated. Danilo has an existing partner, Piero, a shirt-maker who represents an older, more stable relationship. Nicholas knows about Piero, and Piero knows, in a broad way, about “folds” in their life together.

The three men don’t form a simple triangle so much as overlapping worlds, and Nicholas’s presence intensifies Danilo’s sense of being split between versions of himself.

Nicholas, meanwhile, is still fleeing. London, Alan, and his own earlier hustling are things he forces away by narrating his present out loud whenever the memories surface.

He depends totally on the identity Danilo gives him: apprentice, page, lover, mozzo, artist in training. His hunger to be told who he is – to wear costumes and roles instead of inventing himself from scratch – makes him both grateful and dangerously pliable.

Pasolini and Salò: another film, another father

Running alongside Casanova is another production: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Danilo is working on that too, and Nicholas gradually finds himself drawn into Pasolini’s orbit.

The first time he rides in the director’s silver Alfa Romeo, Nicholas feels a physical jolt at the proximity of Pasolini’s taut, wiry body.

Pasolini is older even than Danilo, intensely self-contained, dressed in tight jeans and shirt – a deliberately unshowy masculinity very different from Danilo’s theatrical camp. Their conversation veers oddly from Nicholas’s London paintings of fires to English football teams, and Nicholas senses both the director’s nervousness and his curiosity.

Nicholas begins translating Pasolini’s poems, spending Easter at a farmhouse location outside Mantua where Salò is being shot.

The dynamics there are different from Cinecittà. Pasolini moves easily among the boys from the nearby villages who serve as extras and hustlers, teasing them, listening seriously to their complaints, buying them cigarettes. He seems both paternal and erotically charged, and the boys are drawn to him because he takes them seriously in a way no one else does.

During a lull over Easter weekend, Danilo goes to visit his mother and most of the crew go home. Nicholas volunteers to stay and guard the house rather than endure family festivities that would emphasize his status as an orphaned stray.

Alone in the farmhouse with Pasolini, he finally confronts Alan’s death. Over coffee and then in a fire-lit room with mirrored walls, he tells Pasolini the whole story: the older married man, the mirrored flat in London, the subtle but very real pressure for money, and the headline that forced him to run.

Pasolini listens, occasionally reaching out to touch Nicholas’s leg or hand, gently insisting he isn’t solely to blame. For Nicholas, this confession feels like both exposure and absolution; yet it also deepens his entanglement with the director.

The missing reels: complicity and blackmail

Money is a constant problem for these films, and soon Nicholas’s desire to please drags him into more dangerous tasks. One night, after too much drinking in a gay bar near Termini, his colleague Ettore makes a proposition.

It’s “really simple,” Ettore says: Nicholas just has to do what he did before, except that this time he’ll pick up film reels instead of dropping them off.

When Nicholas protests that this is theft, Ettore shrugs and calls it a Neapolitan game – more like a pressure tactic than a crime. Someone owes someone; the reels are “borrowed” as leverage, then returned.

Nicholas agrees. At Technicolor he uses his new insider status and his English charm to bluff his way into the right room and walk out with canisters containing crucial footage from both Casanova and Salò.

The theft is meant to send a message to the films’ producer, Grimaldi, about money and control. No ransom is ever clearly paid; the reels are hidden, and everyone behaves as if this is just another piece of chaotic Italian business.

But the reels from Salò—including its final, climactic sequence—never fully find their way back, and in history as in the novel, portions of the film remain lost.

Nicholas can’t shake the feeling that he’s crossed a line. His earlier life with Alan already made him feel like an accessory to someone else’s corruption; now he’s participating in blackmail around a film that is literally about fascism, torture, and the complicity of bystanders.

The pressure accumulates without fully registering until much later.

Ostia: the night of Pasolini’s death

The turning point of the book is Pasolini’s murder.

Before that night, Nicholas has already tasted the rough camaraderie of an earlier Ostia trip, when he rides his yellow Vespa out to the coastal football field to watch Pasolini play with a group of local boys.

He loves the feral edges of the place – shacks, rubbish, Roman ruins under the grass – and also the fact that Pasolini has invited him. But even there, amid the scrappy game and the blazing sun, Nicholas feels slightly surplus: another boy among boys, not sure what part he plays.

Months later, on a November weekend around All Souls’ Day, Ettore tells Nicholas there will be a “handover” that night. The stolen reels are going to be returned to “your friend” Pasolini, and the message from Grimaldi’s people is that Nicholas should go to the bar and “just check it all goes okay.”

One of the Termini hustlers will ride with Pasolini. Nicholas doesn’t want to go; his hands shake when he washes his brushes. But he also thinks that if the reels are given back, his slate might finally be wiped clean.

That night he stands outside the bar as Pasolini’s silver Alfa pulls up. There’s a brief comic interlude as two drag queens flirt at the car window and are rebuffed. Then Pasolini picks out a boy from the small cluster on the pavement – one of the familiar Termini kids – and the boy slides into the passenger seat.

Nicholas, sliding through the crowd to his Vespa, feels the now-familiar shift into a more competent self: the version of him that can follow a car through Rome’s Saturday-night traffic as if it’s a dance. He trails the Alfa past the Colosseum, then out of the city towards Ostia and the sea, stopping when they stop, waiting while Pasolini and the boy eat in a roadside restaurant.

They drive out along the same dirt track Nicholas used for the earlier football match, past shacks and rubbish, parallel to the river.

Eventually the car pulls into a field. Nicholas watches the two silhouetted figures negotiate, sees Pasolini smiling, and then sees him bending his head towards the boy’s crotch. At that point something in Nicholas snaps. He realizes that he doesn’t need to stay and watch, that “fuck the reels” – let the man have sex in peace.

He paddles the scooter round in the grass and rides back towards Rome, effectively abandoning the mission and leaving the boy alone with Pasolini at an isolated building site by the sea.

The next morning, at Cinecittà, news trickles through the set of Casanova. Fellini is in the middle of coaxing an actress through a humiliating exercise when his secretary bursts in to speak to him; he and several men hurry out together.

Danilo goes straight to Fellini and clutches him like a child; both of them are sobbing. The radio announces that Pasolini’s body has been found on waste ground at Ostia, that a seventeen-year-old named Pelosi has been arrested driving his silver Alfa, and that the director has been beaten to death and then run over.

Over the next days Nicholas and Danilo are glued to the papers. The photographs of the mangled body are obscene; Nicholas tries to take them away, but Danilo insists on seeing his friend.

The official story – a sex date gone wrong when Pasolini tried to do something monstrous with a stick – is grotesque, and Dani angrily insists that the world is eager to believe it because it confirms their prejudices about Pasolini as a dirty, death-loving pervert. “They have killed Salò too,” he says bitterly: now people will watch it as the fantasy of a man who got what he deserved.

Nicholas internalizes this fury, but he also feels something worse: personal culpability. When he reads Pasolini’s final interview – in which the director warns that “we are all in danger” from a rising system of violence and greed – Nicholas thinks, “Me.”

He was the one who helped steal the reels; he was the one invited to Ostia as a moral witness and then chose to turn back. Violence buys silence, he realizes, and most people, unlike Pasolini, are ruled by fear.

At the funeral in Campo de’ Fiori, the square is packed. The boys Pasolini loved and listened to stand in their jeans, some impassive, others raising their fists as the coffin passes. Back at the flat, Danilo mutters that he’d like to burn his suit and never wear it again.

Nicholas knows, with a cold clarity, that these are their last moments together.

Pasolini saw everything that was coming politically and yet was blind to his own vulnerability; Nicholas feels similarly split, like Oedipus, suddenly aware of the havoc he has caused without meaning to. Love, he realizes, is part of the punishment: leaving Danilo – the person he loves most – is the only way he can imagine taking responsibility for the harm he’s helped to do.

Ending: London, Casanova, and the remains

The final pages jump forward. Nicholas is back in London during a heatwave, sweating into his shirt as he wanders the streets. He ducks into the Curzon cinema just to get out of the sun and discovers that Fellini’s Casanova is playing – a film he has never actually seen in its finished form.

Sitting in the dark, he watches his former life flicker on the screen.

There is Sandy singing in the bathtub; there is the boat that broke in two during filming; there are sets and props he remembers helping to paint – the pink coat, the magic mirror, the ridiculous rhino with a metal phallus – all now part of the film’s seamless illusion.

He realizes that, for anyone else in the audience, these images are just baroque extravagance, but for him they are an archive of his own vanished world, his love affair, his guilt and complicity.

The experience is both consoling and desolating. On one hand, Danilo’s work has endured; the illusions he conjured are immortalized in celluloid. On the other, Nicholas’s own art – the paintings he once wanted to make – has dissolved into those same illusions.

At one point he imagines that perhaps his paintings are somewhere on a back wall of the set, painted over and repurposed; his artistic self has become part of the scenery for someone else’s story.

When the film ends, Nicholas steps out into the bright London street. The book closes not with tidy redemption but with a sense of open-endedness. He is no longer the fleeing boy of 1974, nor the adored apprentice in Venice and Rome, nor the accomplice asleep at the wheel of history.

He is simply a man walking out of the cinema into the present, carrying with him both the weight of what he’s done and the knowledge that, like everyone in Pasolini’s warning, he lives in a world where illusion, violence, love and guilt are all tangled together.

4. The Silver Book Analysis

4.1.The Silver Book Characters

Laing’s people are never just individuals; they’re also bodies carrying history, shame and desire into every frame.

Nicholas Wade is written as both a specific young man—red-haired, art-school trained, grieving a dead lover—and a kind of stand-in for queer men subject to blackmail, police harassment and media scapegoating in the 1970s.

Early in the book he roams Venice with a sketchbook, passing stone beasts, cramped prison corridors and heavy doors, registering a city that feels simultaneously theatrical and claustrophobic.

His artistic eye is sharp, but his emotional judgement is shaky, and Laing uses that combination to show how easy it is to be seduced by someone more powerful who offers you work, shelter and a story to step into.

Nicholas wants to disappear into the role of Danilo’s apprentice and lover, yet he drags his own secret—what he did or didn’t do in London—like a phantom reel that may surface at any moment.

I found him frustrating, moving and recognisable, especially in the way he mistakes proximity to genius for safety.

Danilo Donati, by contrast, arrives on the page fully formed: a heavyset, quick-witted magician of fabric whose mixture of swagger, melancholy and oddly tender hands keeps Nicholas permanently off balance.

Pasolini later appears as an austere, watchful presence whose quiet confession over dinner—that he too is marked by a death—collapses erotic guilt, survivor’s guilt and political responsibility into a single shared burden.

Even tertiary figures—extras shivering in powdered wigs, hustlers at Termini, the boyish guard on the set of Salò—feel like distinct nodes in the same network of risk and desire rather than faceless background dressing.

4.2. The Silver Book Themes and Symbolism

For me, The Silver Book is fundamentally about illusion—cinematic illusion, erotic illusion, and the political illusion that violence happens somewhere else, to other people, while we simply watch.

Laing uses the contrast between Fellini’s hallucinatory extravagance and Pasolini’s severe, punishing aesthetic to stage a debate about what art should do in times of creeping authoritarianism: dazzle us, or force our eyes open.

As the lovers move from the artificial canals of studio Venice to the stark, rural locations of Salò, the book keeps asking whether beauty is a form of complicity or a necessary shelter for the oppressed.

The recurring imagery of prisons, locked doors and narrow viewing apertures—literal cells in the Doge’s Palace, screening rooms, camera lenses—turns the reader into another spectator wondering what we’re not being shown.

Laing has said that the title came quickly because both films are filled with mirrors and reflective surfaces, and the novel runs with that idea: silver is the colour of both cinema reels and the mercurial self you glimpse and distrust.

Nicholas is constantly catching sight of himself—literally in mirrors, figuratively in Danilo’s stories and Pasolini’s politics—and each reflection asks whether he is witness, accomplice or potential victim.

Underneath the film lore and erotic charge, I read the book as a warning about how easily liberal societies slide toward a soft, consumerist fascism while their artists are busy arguing over style.

5. Evaluation

The first strength that hit me is sentence-level: Laing writes with a tactile precision that makes fabrics, carpenters’ glue, scooter exhaust and late-night anxiety feel equally real, and that sensory density is a huge part of the book’s pleasure.

Their choice to structure the novel as rapid, vignette-like scenes keeps the narrative humming; even when not much “happens”, the cuts between Venetian palazzi, Roman studios and roadside cafés generate a feeling of movement that matches Nicholas’s restless inner state.

I also loved how unapologetically queer the romance is: Danilo is never a tragic stereotype but a fully powered adult whose flaws stem from his power, not from his sexuality, and Nicholas’s desire is treated as both exhilarating and dangerous rather than shameful.

The novel’s refusal to smooth out Pasolini into a saint—he’s prickly, sometimes cruel, yet fiercely lucid about the rise of a new kind of fascism—gives the political thread bite.

For readers who enjoy books where ideas about cinema, sexuality and power are smuggled inside an engrossing story, The Silver Book is a rare combination of brainy and propulsive.

At the same time, I agree with some critics that the novel’s breathless, snapshot structure can flatten its darker material; sometimes the horrors of Salò and the real terror of the Years of Lead feel like aesthetic backdrops rather than fully confronted realities.

A few side characters remain more types than people, and the late-stage plot around stolen reels and conspiracy, while thrilling, occasionally strains credibility in ways that pulled me out of the otherwise convincing world.

When I think back on the book, though, what stays with me is not the plausibility of the mystery but the ache of watching Nicholas realise that his search for escape has only led him deeper into the very systems—of desire, of cinema, of politics—that were already hurting him.

Compared with Laing’s essayistic work like The Lonely City or the autofiction of Crudo, The Silver Book feels closer to the kind of hybrid you and I might associate with novels about film such as Day for Night or the Borgman-adjacent cinema you’ve explored on Probinism—works where the making of art becomes the main drama.

What links this novel to the books and films are—Persona, Satantango, A Man for All Seasons, even Boyhood—is an obsession with how individual conscience and perception are shaped by larger structures: church and state, ideology and image-making.

Like Bergman and Krasznahorkai, Laing leans into ambiguity; Nicholas is no pure victim, and the systems surrounding him are too complex for simple denunciation, which is exactly what makes the book feel emotionally honest rather than didactic.

Readers who enjoyed the moral wrestling and slow-burn pacing of those works will likely recognise the same willingness here to sit with discomfort, to let meaning accrue gradually rather than via plot twists alone.

So far there is no announced screen adaptation of The Silver Book itself, although the novel is built around two existing films—Casanova (1976) and Salò (1975)—whose own production histories and box-office paths are part of cinema lore.

In a way, Laing has already done the adaptation work in reverse: instead of a movie based on a book, this is a book that remixes and deepens the meanings of films whose shocking images once struggled or succeeded at the box office but later became cult artefacts studied in film schools and retrospectives.

Given the novel’s cinematic structure and the recent wave of prestige limited series about directors and scandals, I wouldn’t be surprised if a streaming adaptation eventually emerges, but at the time of writing all “box-office data” relevant to The Silver Book is really the early cluster of strong critical reviews and pre-publication buzz, with Book Marks already logging eleven largely positive reviews.

6. Personal Insight

In the classroom or seminar room, I’d place The Silver Book alongside works on media literacy and authoritarianism, because it dramatises how images do political work long after their makers are gone.

Reading Laing alongside current news about rising far-right parties in Europe and algorithmic radicalisation, I kept thinking about Pasolini’s 1970s essays warning that consumer capitalism would birth a new, more insidious fascism—a diagnosis many political theorists now treat as uncannily prescient.

In an educational context, the novel gives you a vivid case study for courses on film studies, queer history or political science: students can move from the fictionalised sets of Salò to analysing how contemporary platforms weaponise shock imagery, memes and “aesthetics of outrage” to normalise cruelty.

Because Nicholas is not a hero in the traditional sense—he compromises, looks away, lets himself be dazzled—the book invites readers to map their own small complicities, just as you do in your Probinism essays on Foucault, cancel culture and the machinery of rights.

I can imagine a seminar where students pair The Silver Book with a viewing of Casanova or Salò, then with a modern film like Persona or even a long-form project such as Boyhood, asking at each step who controls the image and whose body pays the price of that control.

Used this way, Laing’s novel stops being “just” historical fiction and becomes a flexible teaching tool for discussing consent, censorship, propaganda and the ethics of spectatorship, which feel like core literacies for anyone growing up under today’s overlapping media and surveillance regimes.

Later, as Danilo reflects on Fellini’s project, he realises that Casanova is “a film about the cost of illusion”, and that realisation spills over the boundaries of the movie into Nicholas’s life and, by implication, our own.

8. Conclusion

If you’re drawn to novels where queerness, cinema history and political dread shimmer together in one dangerous, beautiful reel, The Silver Book is absolutely worth reading—though it may leave you, as it left me, a little more suspicious of every gorgeous image you see.