Last updated on June 23rd, 2024 at 07:13 pm

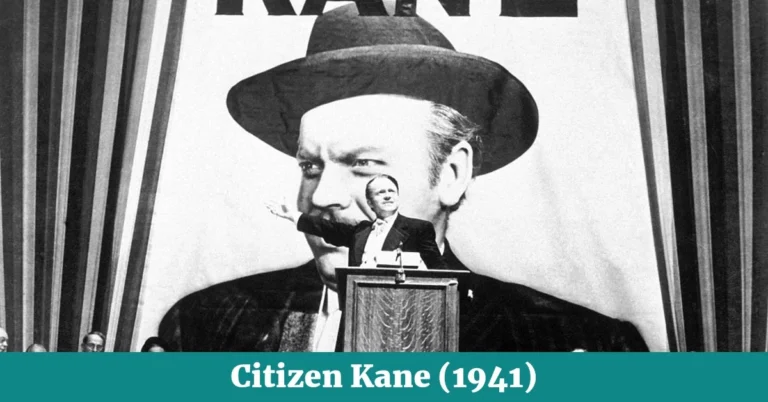

Citizen Kane is a 1941 American drama film directed and produced and starred by Orson Welles, who also co-wrote, starred in, and edited the film. The film follows the life of Charles Foster Kane, a powerful and wealthy newspaper tycoon who rises to fame and fortune, but ultimately falls from grace as he becomes more and more isolated and unhappy.

Citizen Kane is widely considered one of the greatest films ever made and is known for its innovative use of flashbacks and non-linear storytelling, as well as its powerful performances and technical achievements.

Background

From 1962 until 2012, Sight & Sound magazine’s oft-cited critics’ poll of the greatest films ever made placed Citizen Kane, Orson Welles’s remarkable debut film, at third on the list.

By 1998, the American Film Institute called it the greatest movie of all time, placing at number one among the 100 greatest. It also garnered Best Picture awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Board of Review and won an Oscar for its screenplay.

Acted by Dorothy Comingore (Susan Alexander Kane), Agnes (Mary Kane) Moorehead, Ruth Warrick, Ray Collins, Orson Welles (Charles Kane), Joseph Cotten (Jedediah Leland), Ruth Warrick (Emily Monroe Norton Kane) and others, Citizen Kane 1941 number 2 film of the British Film Institute, 4th best film of all time according to Cinemarealm and was enlisted in National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1989.

The legend of Citizen Kane has partly been intensified by the fact that Welles was only twenty-four when he made the film, but also from the obvious comparisons between the ostensible character and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, known as the prophet of yellow journalism, who undertook every possible move to stop the film from being made—and then, when he could not stop it from being distributed, tried to vilify it and stopped any kind of viewing or reviewing of the film on his newspapers. But beyond the preposterous publicity of any single film being “the greatest movie of all time,” Citizen Kane is of tremendous interest and importance for various reasons.

Charles Foster Kane is a fictional character that is slightly based on the life of William Randolph Hearst. Hearst was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation’s largest newspaper chain and yellow journalism. Circulation of the newspaper by featuring sensationalism, human interest, crime, sex, corruption, and innuendo was his main objective.

The film tells a great story of Charles Foster Kane, who was born poor, but strikes it rich through a gold mine bestowed to his mother. As a young man, he begins to assemble a mainstream newspaper and radio empire, eventually marrying the niece of an American president and running for governor. But any ambition he has for real power is thwarted.

As Kane becomes estranged from his power, he becomes increasingly abusive to the women in his life, first his wife, and then his lover. He dies, almost alone at the end of his life, in his reconstructed but unfinished castle, longing for the simplicity of his childhood. Firmly within the traditions of populism, a political approach that strove to stir ordinary people of America, Citizen Kane praises the very American perspective “that money cannot buy happiness”, but in a highly simplistic way. More significantly, Citizen Kane begins with Kane’s death, and the enigmatic final word he utters: “Rosebud.”

After his death, a group of fearless newsreel reporters try to discover the meaning of this last word and interview several of Kane’s friends. Not only is the film told in flashback, but each character only knows the man from a certain perspective, which is presented in due course.

The film begins with Kane’s death and the search for the meaning of his last word, “Rosebud.” The story then unfolds through a series of flashbacks and interviews with those who knew Kane best, including his best friend, his wife, and his business associates. The film ends with the revelation that “Rosebud” was the name of the glass ball Kane had as a child and symbolizes the innocence and happiness he lost as he rose to power.

As the story unfolds, we learn about Kane’s humble beginnings as an orphan who is taken in by a wealthy mining tycoon, who raises him as his own and gives him a vast fortune. Kane uses this fortune to build a powerful newspaper empire and becomes a powerful political figure.

Citizen Kane portrays the rise and fall of a publishing tycoon in America. However, Kane’s ambition and desire for power lead him to become increasingly ruthless and isolated. He alienates those closest to him, including his wife and best friend, and ultimately dies alone and unhappy. This is one of the 101 best films of 100 years of my listing.

Citizen Kane is perhaps the one American talking picture that seems as fresh now as the day it opened. It may seem even fresher. A great deal in the movie that was conventional and almost banal in 1941 is so far in the past as to have been forgotten and become new.

It is difficult to explain what makes any great work great, and particularly difficult with movies, and maybe more so with Citizen Kane than with other great movies, because it isn’t a work of special depth or a work of subtle beauty. It is a shallow work, a shallow masterpiece. Those who try to account for its stature as a film by claiming it to be profound are simply dodging the problem—or maybe they don’t recognize that there is one. Like most of the films of the sound era that are called masterpieces, Citizen Kane has reached its audience gradually over the years rather than the time of release.

Storyline

Charles Foster Kane of Citizen Kane film 1941 died in his pleasure dome, Xanadu. He let his glass ball go off, which he was holding dearly, and uttered his dying word ‘Rosebud’. The rest of the 1941 drama film evolved around the Rosebud that revealed, gradually, story after story about the life of a newspaper tycoon of the USA and how he built his estate empire.

Like most Mongol emperors, Kublai Khan’s pleasure dome Xanadu, about which in 1275 the traveller Marco Polo described to have “the rooms of which are all gilt and painted with figures of men and beasts and birds, and with a variety of trees and flowers, all executed with such exquisite art that you regard them with delight and astonishment”, Kane’s Xanadu lacks nothing of the sort. Samuel Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan opens as:

“In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea”

Citizen Kane-1941 starts with a short narration. The narrator narrates that Kane of Florida built a private pleasure ground as legendary as the Xanadu of Kublai Khan. On a private mountain of Florida’s Golf Coast, he built America’s Xanadu with one hundred thousand trees, and twenty thousand tons of marble. Among the collections are paintings, pictures, statues, various stones of other palaces, Spanish furniture, jigsaw puzzles, the fowl of the air, the fish of the sea the beast of the field and the jungle.

So big was Kane’s Xanadu that it is enough for 10 museums, the loot of the world, and the biggest private zoo since Noah. Like the pharaohs, the narrator narrates, “Xanadu’s landlord leaves many stones to mark his grave. Since the pyramids, Xanadu is the costliest monument a man has built to himself”.

Known as America’s Kublai Khan and landlord of Xanadu, Charles Foster Kane, the greatest newspaper tycoon of any other generation, he won 37 newspapers- while Hearst 30- and two syndicates, a radio network, apartment buildings, factories, forests, ocean liners, an empire upon the empire.

He is compared to Noah and the Pharaohs as well as to Kubla Khan. Viewed so metaphorically, Kane is more legend than a flesh and blood person. Still, the narrator’s description of Xanadu as nearly the “costliest monument a man has built to himself ” is not far from the mark.

We see, accompanied by American composer Bernard Herrmann’s deliberately fatuous funeral elegy, pallbearers carry his coffin out of Xanadu and through a crowd of mourners, in contrast to the previous scene’s image of Kane alone on his deathbed where he was all alone.

As a result of his death, a series of international newspaper headlines carried report of his death and attest to his status as a cultural icon and a potent man of American history. Then, in an abrupt transition, imagery and music switch gears to tell the story of Kane’s financial empire, from its humble beginnings to its vast and diverse properties. We are narrated how from one dying daily, The Inquirer, Kane built his empire.

The rise and fall of Kane

A boarding housekeeper and a defaulting boarder Mary Kane, Kane’s mother–married to a comparatively older man–gave away her abandoned mineshaft, The Colorado Lode, for 50,000 dollars a year to be given to her and Kane. Walter Thatcher of Thatcher and Company, promised his education and complete possession of the property on his 25th birthday. She made Thatcher a new guardian of Kane and was taken to Chicago. On the other hand, Heart’s father was a millionaire and a gold mining engineer from San Francisco.

After Kane’s death, Newsreel was trying to cover the life of Kane and his ascension to glory. So, doing the reporters decided to find out the meaning of his last word: Rosebud. The newspapers sensationalised his death. Mr. Thompson, the reporter went to anyone who possibly came close to him including his second wife Susan Alexander, his friends, colleagues, and the memoir of Walter Thatcher in Walter Thatcher Library.

Right after Kane’s death Mr. Thompson first went to his second divorced singer wife Susan Alexander. Bereaved and mournful she refused to talk to anyone about anything. Therefore, he was led to the Thatcher Library. Walter P. Thatcher’s memoir reads that on his 25th birthday, Thatcher wrote a letter to Kane about his full responsibility of Thatcher and Company, the world’s largest private fortune.

But Kane wrote, “Dear Mr. Thatcher.” Sorry, I’m not interested in gold mines, oil wells, shipping or real estate. One item on your list intrigues me: The New York Inquirer. Don’t sell it. I am coming back to take charge. I think it would be fun to run a newspaper”. The New York Inquirer was a dying daily, in a ramshackle building where Kane’s fortune began with full editorial control of it.

Mr. Thompson read in the memoir that, after taking charge of The New York Inquirer, he began his yellow journalism. although Mr. Thomson did not find anything about Rosebud, what he was all up to unearth.

Without much information he then Mr. Thompson went to Mr. Bernstein, Kane’s General Manager. He recalled Jed Leland, his long-time friend, and who had been with Kane from the very day he took over the newspaper.

Mr. Bernstein told how Kane came up with the idea of the Declaration of Principles which he published on the front page after he forcefully took over The New York Inquirer from the previous editor.

“There’s something I’ve got to get into this paper besides pictures and print”, recalled Bernstein saying, Kane. “I’ve got to make the New York Inquirer as important to New York as the gas in that light” which he did by sensationalising news with sex, crime, and innuendo and presenting the truth warped manner.”

“His Declaration of Principles on the front page bears, “I’ll provide the people of this city with a daily paper that will tell all the news honestly. I will also provide, that people will know who’s responsible and they’ll get the truth in the Inquirer, quickly, simply and entertainingly. No special interests will be allowed to interfere with that truth”.

The next day Inquirer circulated 26,000 copies. But Kane declared to buy off all the staff of the Chronicle which took for it 20 years to reach 500,000 circulations. Once they were taken to The New York Inquirer, its circulation leapt as much as 684000 the next morning. Kane flew to Paris for a vacation after a ‘success celebration’.

Mr. Bernstein remembered that 467 employees of the New York Inquire welcomed him as he returned from France. on the event, while all employees were waiting to receive him with a big trophy, he let them know that could not accept the party because he did not have time.

But he told, by giving a note, the social editor of the new paper to publish a social announcement, that he is going to be engaged with Mrs Emily Norton, niece to the president of the USA.

Mr. Bernstein told Mr. Thompson that it is not Emily whom he would call ‘Rosebud’. He rather suggested that the ‘Rosebud’ they were looking for might be something he lost, not someone lost or loved. He then started to find out about Kane’s friend, Mr. Jedediah Leland.

Mr. Thompson, however, found Jed Leland in a hospital. He remembered to Thompson, “I was his oldest friend, and as far as I was concerned, he behaved like a swine. Not that Charlie was ever brutal. He just did brutal things”.

Mr. Thompson asked him if he knew anything about Kane’s dying word: Rosebud. Instead, Mr. Leland recalled Kane’s first love, Emily Norton. He said even though they were happily married they got into a rivalry because of what Kane would print in his newspaper, attacking her president uncle.

Over time, their interests parted, she for the president, and him against the president. She would read a different daily in front of him while Kane basked at his brainchild, The New York Inquirer. Emily despised his footing in political affairs.

Kane ran for the governor of the state with the purpose of defeating a professional politician Boss Jim W. Gettys, which he said would do by making public his dishonesty, the downright villainy and his political machine. In his election campaign, Kane severely attacked to sway voters.

Mr. Leland revisits that, in the meantime, Kane accidentally fell in love with Susan Alexander, a singer with minimal singing talent. Jim Gettys just did not let slip his chance through Kane’s fingers. He went as far as to exploit their affair as a political ploy against Kane.

Jim Gettys made Susan write a threatening note to Kane’s wife Emily: “Serious consequences for Kane, for you and your Son”. With the note Emily, after a campaign, forced him to meet with Jim Gettys to deal with the matter in a nearby house where Susan was present.

Gettys demanded Kane that unless Kane decides by the next day that he is ill and has gone away for a year, all the newspapers of the state, except Kane’s, will carry the story that gives. The story about Kane and Susan.

Emily implored Kane to listen to ‘reason’ and do what Gettys had said. Susan too told him to consider his family instead of the concerns and love of the voters of the state. But Kane declared that “There’s only one person in the world to decide what I’ll do. And that’s me. I’m Charles Foster Kane! I’m no cheap, crooked politician trying to save himself from the consequences of his crimes!” Emily left, divorced and died with her son in a car accident, alter.

The next morning the newspapers of the state carried the love story between Kane and Susan Alexander, the singer. Still, Kane remained unrelenting about the election.

Defeated, Kane plunged in the deep prostration. His long-standing friend Jed Leland blamed Susan for his defeat. The next day his newspaper carried a headline that the election fraudulence was responsible for his defeat. And Jed Leland told him that he wanted to work with a different daily, The Chicago.

Mr. Leland recalled that Kane married Susan afterwards. As per her wish of becoming an opera singer, he built her an Opera House expending millions. And Kane fired Jedidiah after finding him asleep drunk on his typewriter in his office while writing a review for The New York Inquirer criticising the musical talent of Susan Alexander.

After Leland Thompson went back to Susan again and trying to quiz information about Kane and his dying word. She recalled how they were separated during a picnic after a few days Jed Leland published an editorial note about her musical talent. During a picnic, Susan complained to Kane that he never had given her anything that she wanted.

She objected that there is no difference between giving her something and giving away 1,000 dollars for a statue, and she never wanted him to build an opera house for her. It was rather his idea to win her love for him. It is just the money which does not mean anything, but all the time he was trying to buy her by giving her something.

But Kane replied with a furious voice, “Whatever I do, I do because I love you”. She told the reporter that she left Kane in the picnic after he slapped her in the face.

What is Rosebud in Citizen Kane?

Without having anything about, ‘Rosebud’, Mr. Thompson went to Xanadu to meet with its caretaker. He recollected that after Susan had left him, he became frustrated and started breaking and throwing things inside the room and picked up the glass globe and uttered ‘Rosebud’.

He said ‘Rosebud’ was nothing but the name of a glass ball, one of the collections of many things. he liked to collect anything and everything. statues of Venus, a Burmese temple, a Spanish ceiling, paintings, and toys. He was a man who got everything he wanted and then lost it.

To conclude, when men came and started auctioning and incineration the contents of Xanadu, a piece of furniture printed ‘Rosebud’ was seen burning in the fire. A man who was so mad in collecting things ended up holding a thing that meant nothing to anyone. A glass ball and a piece of furniture by the name of ‘Rosebud’ became his dying word.

“He couldn’t get or something he lost. I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life”, says one of the employees of the insurer. after his death, the collections of million-dollar worth were thrown in the fire and regarded as junk. In fact, the mystery behind ‘Rosebud’ revealed the mystery of Kane’s life.

Citizen Kane quotes

There are some marvellous quotes from the film. The following are a few of them.

Well, it’s no trick to make a lot of money. If all you want is to make a lot of money. You take Mr. Kane. It wasn’t money he wanted”.

Charles Forter Kane, Citizen Kane 1941

“Just old age. It’s the only disease that you don’t look forward to being cured of”.

Walter Parks Thatcher: “The greatest curses ever inflicted on the human race: Memory”.

“My reasons satisfy me, Susan.”

“Yes. Dear Wheeler: You provide the prose poems; I’ll provide the war”.

Mr. Bernstein: A fellow will remember a lot of things you wouldn’t think he’d remember. You take me. One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry. And as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in, and on it, there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn’t see me at all. But I’ll bet a month hasn’t gone by since that I haven’t thought of that girl.

Jedediah Leland: “That’s all he ever wanted out of life… was love. That’s the tragedy of Charles Foster Kane. You see, he just didn’t have any to give.”

Susan Alexander Kane: You don’t love me. You want me to love you. Sure, I’m Charles Foster Kane. Whatever you want, just name it and it’s yours. But you’ve got to love me!”

Charles Foster Kane: “As Charles Foster Kane who owns 82,364 shares of Public Transit preferred, you see, I do have a general idea of what the public wants. But I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep it up with my little weekly.”

Charles Foster Kane: “If I hadn’t been very rich, I might have been a really great man.”

Jedediah Leland: “You know, it’s a pity you don’t believe in anything except your own greatness.”

Overview

This modern morality may well startle an unsuspecting audience accustomed to having a good deal of jam with its satirical powder.

The satire here is as savage as Swift’s, and in its unrelenting light the victim becomes positively nauseous; yet the treatment is brilliant and continuously pleases the aesthetic sense. Citizen Kane is the owner of a chain of American newspapers, and through the Kane Press, he can give unedited expression to the grandiose workings of an essentially trivial mind.

The film fastens in the end on the magnate’s attempt to create a satellite wife worthy of his millions. She is a hopelessly incompetent singer, but he buys opera houses, critics, orchestras, and singing masters in the almost maniacal resolve to make her famous in opera.

The wretched woman, who knows she cannot sing, is forced to continue her fantastic career until exposure to ridicule produces a nervous breakdown. All the horror of her ordeal is conveyed with extreme economy of means and unsparing cruelty.

Their home is a palace which even Mussolini would think a little too palatial, and they are surrounded with costly works of art which have meaning only for others. When she shouts across vasts of marble flooring the wish to go on a picnic a dozen limousines are driven to a private beach. When she leaves her husband she walks away along an interminable corridor, slamming innumerable doors, and he is left with his loneliness reflected in a hundred ornate mirrors.

Then he gives way to an orgy of destruction, and he dies, and the apparatus of happiness which money has bought is sold to the dealers and great bonfires burn. These last scenes are masterly in their fierce, cruel ridicule of a rich man who, do what he will, cannot buy happiness and has absolutely no other idea of how it might be procured. There is not much acting, there is no need for it: the rare distinction of having made a film entitled to rank as a work of art belongs almost exclusively to the director, Mr. Orson Welles.

Why Citizen is Politically Important

Acted and directed by Orson Welles and released in 1941, Citizen Kane is politically significant for several reasons:

1. Critique of Media Power and Influence

- The film is widely interpreted as a critique of the media’s power to shape public opinion and influence politics. The character of Charles Foster Kane, a wealthy newspaper magnate, is often seen as a portrayal of William Randolph Hearst, a real-life media tycoon. Hearst’s newspapers wielded substantial political influence, and “Citizen Kane” highlights the potential dangers of such concentrated media power.

2. Reflection on the American Dream

- Citizen Kane explores the complexities and contradictions of the American Dream. Kane’s rise to power and subsequent moral decline reflect the potential corrupting influence of wealth and ambition. This theme resonates with political discourse about the nature of success, individualism, and the ethical responsibilities of the wealthy and powerful.

3. Censorship and Political Backlash

- The release of Citizen Kane itself was politically charged due to Hearst’s vehement opposition. Hearst used his influence to try to suppress the film, threatening to expose Hollywood scandals and refusing to advertise RKO pictures (the studio behind the film) in his newspapers. This battle over censorship and freedom of expression underscores the political tension surrounding media and its role in society.

4. Examination of Populism

- The film delves into Kane’s political ambitions, including his run for governor. Kane’s character is shown as a populist figure, using his media empire to sway public opinion. This aspect of the story serves as a commentary on the use of media for political gain and the potential manipulation of the masses by charismatic leaders.

Charles Foster Kane as a Populist Figure

- In Citizen Kane, the character Charles Foster Kane embodies many traits of a populist leader. His political career is marked by efforts to position himself as a champion of the common people, often using rhetoric and strategies designed to appeal directly to the masses.

Manipulation of Public Opinion

- Kane’s control over his vast media empire allows him to shape public opinion to his advantage. This reflects a key aspect of populism, where leaders often rely on direct communication with the public, bypassing traditional political institutions and using media to cultivate a strong, personal connection with the electorate. Kane’s newspapers promote his political ambitions, sensationalize news to attract readership, and present him as a savior of the common people.

Campaign for Governor

- Kane’s gubernatorial campaign is a central plot point in the film, showcasing his populist tactics. He promises reforms and positions himself against the corrupt political establishment, echoing the populist narrative of fighting for the people’s interests against elite power structures. His speeches and public appearances are crafted to resonate with ordinary citizens, emphasizing his commitment to their welfare and portraying himself as their advocate.

Rhetoric and Charisma

- Kane’s populist appeal is further amplified by his charismatic personality and compelling rhetoric. He uses simple, direct language and emotionally charged messages to connect with voters, a hallmark of populist leaders. His ability to engage and mobilize large crowds underscores the effectiveness of his populist strategy.

Conflict with Traditional Elites

- Throughout the film, Kane’s populist approach puts him in direct conflict with established political and economic elites. This mirrors real-world populist movements, which often arise in opposition to perceived entrenched power structures. Kane’s disdain for traditional politicians and his efforts to undermine them are central to his populist identity.

Demagoguery and Ethical Ambiguities

- While Kane’s populist rhetoric initially appears to champion the common good, the film gradually reveals the darker side of his ambitions. His manipulation of information, willingness to bend the truth, and pursuit of power for personal satisfaction highlight the ethical ambiguities and potential dangers of populist demagoguery. Kane’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the seductive allure of populism and the moral compromises that can accompany it.

Personal Ambition vs. Public Service

- Kane’s political journey underscores the tension between personal ambition and genuine public service, a frequent theme in critiques of populism. Although he claims to serve the people, his actions often reflect a deeper desire for control and recognition. This duality is a critical aspect of the film’s exploration of populism, illustrating how leaders may exploit populist sentiments for their own ends.

Legacy and Reflection

- The portrayal of Kane’s populism in “Citizen Kane” remains relevant as it mirrors the rise of contemporary populist movements worldwide. The film prompts viewers to reflect on the nature of political power, the role of media in shaping democratic discourse, and the complex relationship between leaders and their followers in a populist context.

5. Historical Context

- Released during a time of significant global upheaval (World War II), “Citizen Kane” reflects the anxieties and uncertainties of its era. The film’s critical perspective on power, corruption, and media influence is particularly poignant given the contemporary context of propaganda, authoritarianism, and the role of the press in shaping wartime narratives.

6. Legacy and Influence

Citizen Kane has had a lasting impact on both film and political discourse. Its innovative narrative structure and cinematic techniques have influenced countless filmmakers. Politically, its themes continue to be relevant, providing a lens through which to examine contemporary issues of media ethics, political power, and the nature of personal ambition.

In summary, Citizen Kane is politically important because it offers a penetrating critique of media influence, explores the dark side of the American Dream, challenges censorship, and provides insight into the dynamics of political power and populism. Its enduring relevance ensures its place as a significant cultural and political artifact.

In his book What Ever Happened to ORSON WELLES? Joseph McBride writes about politicization of Citizen Kane: “British film critic Laura Mulvey’s 1992 monograph on Kane focuses attention on its antifascist themes of Citizen Kane, which have received far less attention than its formal aspects or the controversy over its roman à clef (a novel in which real people or events appear with invented names) exposure of Hearst’s private life.

- Welles scathingly satirizes Kane’s hobnobbing with Hitler and other dictators while the publisher smugly assures the public that “there’ll be no war.” Mulvey notes that the film reflects “the battle between intervention and isolationism [that] was bitterly engaged in America, with President Roosevelt unable to swing the nation into support for his interventionist policy. ..Not only was the war in Europe the burning public issue of the time, it was of passionate personal importance to Orson Welles, with his deep involvement with European culture and his long-standing political commitment to Roosevelt’s New Deal and the anti-fascist struggle. . . . In the rhetoric of Citizen Kane, the destiny of isolationism is realised in metaphor: in Kane’s own fate, dying wealthy and lonely, surrounded by the detritus of European culture and history.”

however, Journalist Ignacio Romenet thinks Citizen Kane is mass media manipulation example in influencing the democratic process through median opinion and conglomeration. People also consider the media tycoon Rupert Murdock as modern-day Kane.

Conclusion

Even though Citizen Kane 1941 has been considered one of the 100 best films of the time, many may find it unentertaining. It is just a life story of a man who happened to change the history of American politics through newspapers.

Citizen Kane 1941 tells us how the general public can be subjects of the newspaper business. It also tells how news media can be used to exploit public sentiment for personal gains.

Nevertheless, Citizen Kane (1941) will remain one of the best 100 films of 100 years for me.