Last updated on November 2nd, 2023 at 09:51 am

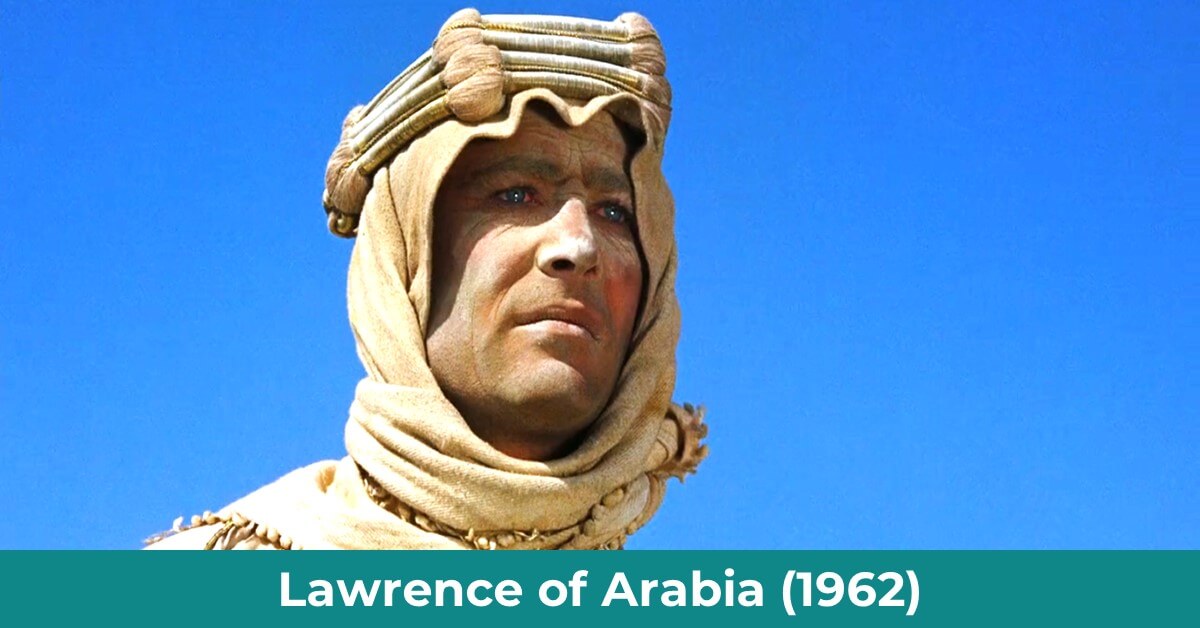

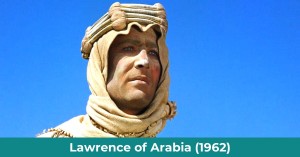

Lawrence of Arabia 1962 movie is one of the best films has been made in Hollywood that portrays the life of the war hero T.E Lawrence based on his autobiographical book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom which depicts his experiences and activities in the Middle East in uniting the warring tribes for Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire and Turco-German forces during World War II.

Came from England, and born to Sir Thomas Chapman and Sara Maden, Lawrence was a British scholar, archaeologist and controversial figure for his role in the Arab revolt as a British liaison officer.

Lawrence of Arabia is one of the best educative and entertaining movies I have ever watched. 207 minutes of run seem very minimal compared to life-like acting and majestic views of the deserts of Jordan, Morocco, Spain and England. Lawrence began his career as a civilian employee of the Map Department of the War Office in London. By December 1914 he became a lieutenant in Cairo, who was seen drawing maps at the beginning of the film.

Directed by David Lean and Produced by Sam Spiegel, Lawrence of Arabia introduces Peter O’Toole as T. E. Lawrence and stars Alec Guinness as Prince Feisal, Anthony Quinn as Auda Abu Tayi, Jack Hawkins as General Allenby, Jose Ferrer as Turkish Bey, Anthony Quayle as Colonel Harry Brighton, Claude Rains as Mr Dryden, Arthur Kennedy as Jackson E. Bentley, I. S. Johar as Gasim in portraying the history of the Middle East in maximum accuracy. It is one of the 101 best on my list to review.

Lawrence, T (Thomas) E (Edward) (1888-1935), sometimes referred to as Lawrence of Arabia, British adventurer, soldier, and author who became famous for his role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

The war years were Lawrence’s most important years. At the outbreak of the conflict in 1914, Lawrence joined the British Military Intelligence Service in Cairo. Here he developed an expertise in Arab nationalist movements. In 1916 he entered in the British EEF (Egyptian Expeditionary Forces) under the command of Archibald Murray.

From 1916 to 1918 he served as a British liaison officer in Arabia and the Levant with Hashemite Arab forces fighting alongside the British around the cities of Mecca and Medina against the Ottoman Turks. Extension of the revolt northwards resulted, in October 1918, in the apogee of Lawrence’s military career when he and the Arabs led by Faisal (later King Faisal I of Iraq) entered Damascus in the vanguard of the advancing British army.

Aqaba was the first major victory over the Turks for the Arab guerrilla forces led by Lawrence on 6 July 1917. Subsequently, Lawrence attempted to organize Arab movements with the campaign of General Sir Edmund Allenby through financial and artillery support. In November, Lawrence was captured at Derra by the Turks while investigating the area in Arab dress and was apparently recognized, bitten and homosexually brutalized before he was thrown outside.

Then, in 1922, in an attempt to escape press publicity, Lawrence made the remarkable decision to give up his rank and position and join the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a ranker under the pseudonym J. H. Ross. Discovered by the press, he was discharged from the RAF, and then in 1923 he joined the Tank Corps under the name T. E. Shaw, where he stayed until 1925.

In 1925 he re-joined the RAF under the name of Shaw and remained there until a few months before his death in 1935. Lawrence produced a candid account of life in the RAF in his 1929 book The Mint. His premature death came in a motorcycle crash in Dorset on May 19, 1935—Lawrence had long been obsessed with machinery and speed, and he owned a succession of state-of-the-art Brough motorcycles while serving in the RAF and Army.

“Lawrence of Arabia” was killed on a Dorset road in the prime of life by a fall from his motor-cycle—the one luxury that he allowed himself—after defying and escaping a hundred deaths in the deserts of Arabia and on the battlefields of Transjordan. He had made history; he had performed exploits that have never been surpassed in the records of irregular warfare; he had passed through trials of the spirit that had neither weakened his amazingly resilient will nor cooled his passion for a fresh experience.

His place in history is assured. Other British officers helped the Arabs of the Hejaz in the campaign that changed the political face of the Near East, but none so effectively or so intelligently as this young archaeologist who had studied war in his school days and had had original ideas of its conduct.

Equally certain is his place in literature. “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom” is worthy of the theme and of the man. It is a marvellous record, clear, incisive, utterly unsentimental, burking nothing of the cruelties and miseries of war; and it will live as long as the fame of this young adventurer of the body and the spirit who tasted and wielded power only to despise its pomps and vanities.

Lawrence of Arabia movie synopsis

The film begins with the death of T. E. Lawrence, also known as Lawrence of Arabia, in a motorcycle accident in 1935. The film then flashes back to 1916, when Lawrence was working as an archaeologist with the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Cairo. He is recruited by the British government to serve as a liaison between the Arab tribes, Harith and Howeitat and the British army. Lawrence quickly became a key player in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, leading the Arab forces to a series of victories against the Turks.

Despite General Murray’s objections, Mr Dryden of the Arab Bureau recruited and sent Lawrence to assess the prospects of Prince Faisal in his revolt against the Turks. Murray gave him only three months. He was provided with a guide, Tafas el Raashid, at Rabigh, to take to Prince Feisals’ camp. Tafas was a Hazimi, a Bedouin, of the Beni Salem branch of Harb, and so not on good terms with the Masruh.

So, when Lawrence and Tafas reached the Mastura well in the desert, he was killed by Sherif Ali ibn el Kharish, a Harith, for drinking water from his well, which was not allowed. Alone, with Tafas’s camel he later met Colonel Brighton at Wadi Safra about two hundred miles north of Jidda and some sixty miles south-west of Medina, where Prince Feisal lived. After ordering him to remain quiet and make an assessment about Feisal, Brighton to Lawrence to Feisal’s camp.

Ignoring Brighton’s order, Lawrence openly expressed his mind of attacking Aqaba, while Brighton advised Feisal to retreat after a major defeat. Lawrence told him of a surprise attack on Aqaba, capturing of which provided the British with a port to bring in much-needed supplies.

For the attack, he asked for fifty men. Led by Sherif Ali, Lawrence reached a well at Wadi Jizil with the fifty men where two teenage orphans, Faraj and Daud were caught spying on them. When caught they threw themselves at Lawrence’s feet to be his servants. As they finished crossing the Nefud desert without rest, Gasim, an Arab warrior from the group fell off his camel due to exhaustion.

When Lawrence realised that the men kept moving without caring about Gasim at the command of Sherif Ali, Lawrence decided to go back to collect Gasim at the pierce of objections of Sherif Ali. Ali said his fate is decided and death is written, who will be dead by the next day. After arguing with Ali that his fate is written only in mind but not in reality, Lawrence went back and rescued Gasim while Daud was waiting for his return.

Lawrence won over the heart of the men, including that of Ali when he got back to the camp with Gasim. Lawrence then said, “Nothing is written unless we write it”.

The next day, Sherif Ali presented Lawrence with the robes of sherif of Beni Wejh at Wadi Rumm, twenty miles north-east of Aqaba where Lawrence met with Auda abu Tayi, the fighting man of the Howeitat tribe. He was a Turk vassal and allowed Turks in Aqaba. At the diner, Lawrence convinced him to fight with them to take Aqaba where he will find gold.

However, Lawrence’s plan was almost foiled as a Harith man killed a man from the Howeitat tribe on their way. Since the killing of the accused by Auda shattered the alliance, Lawrence volunteered to be the judge of the feud, as a man who has no tribal identity. He then executed Gasim on behalf of both sides. But Lawrence was aghast to see Gasim, whom he saved in the desert.

The next morning the Arabs, led by Ali, Auda and Lawrence took over the Turkish garrison. Lawrence then headed to Cairo crossing the Sinai with Daud and Faraj to inform Mr Dryden and the new commander, General Allenby about capturing Aqaba. However, Daud was killed in quicksand before reached Cairo. Though the news of capturing Aqaba was disbelieved initially, Lawrence was promoted to Major for his work and sent back to Aqaba with money and arms.

While still in Cairo, Lawrence asked Allenby whether there is any British ambition in Arabi, as the Arabs suspect. Lawrence wanted to make sure whether the British would occupy Arabia after letting drive out the Turks. Allenby replied that there is none.

Returning to the desert, Lawrence initiated a guerrilla attack on at Ottoman railway linked between Damascus and Medina at Hejaz. Jackson Bentley, an American correspondent from Chicago Courier, wrote about Lawrence’s heroism terming him as ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ who was known to Arabs as Aurens’ or ‘Lurens’ or ‘Runs’ or more wittily as ‘Emir Dynamit’: King Dynamite.

His long companion of journeys, Faraj, had to be killed by Lawrence as he was badly injured by a detonator in a raid. Lawrence had to kill him because falling into the hand of the Turks would have been worse for Faraj. They fled after shooting Faraj. They then plan to take Deraa.

But Lawrence was captured by the Turks when he, along with Ali, went to investigate the city of Deraa. The Turkish Bey tortured him with homosexual intent before he threw him outside where Ali came to his rescue. The experience left him so traumatised that he returned to the British headquarters in Jerusalem in the hope of resigning but was told by Allenby that he was making a push on Damascus and that his service was needed. Allenby urged him to be part of the “big Push” on Damascus, for which Lawrence had to return to the field with stronger support.

This time he recruited an army comprised of murderers and who knew nothing about the Arab revolt. They joined Lawrence merely for money. As they approached Damascus, they saw a column of retreating Turkish soldiers who massacred the village of Talal el Hareidhin, Tafas. Seeing the killing Talal charged forward with a battle cry of “No prisoners” and was immediately killed by the Turkish soldiers.

With a battle cry, Lawrence began killing despite Ali’s objection. Lawrence’s men took Damascus before General Allenby’s force reached it. Damascus was liberated by the Arab army, led by a British soldier, T.E Lawrence, making Feisal a king.

In Damascus, he set up his own headquarters, he presided over the Arab Council in the absence of King Feisal. But the British authority cut off the power and water supplies leaving the tribesmen to debate on maintaining the city. Instead of Lawrence’s efforts to give Damascus to Arabs, they abandoned the city at the hand of the British.

Lawrence was promoted to colonel and sent back to Britain when both, Allenby and Feisal realised the end of his usefulness. Lawrence longingly looked at the travelling Arabs on camels as he was departing by a car.

The film concludes with Lawrence’s return to England in 1918, where he is celebrated as a hero. However, Lawrence is disillusioned with the war and the actions of the British government. He resigns his commission and returns to the Middle East, where he continues to work with the Arab people. The film ends with a montage of Lawrence’s death and his legacy in the Middle East.

Lawrence of Arabia film analysis

The film Lawrence of Arabia, which has a screenplay by Mr. Robert Bolt and which is directed by Mr. David Lean, runs for three hours 41 minutes (exclusive of a 15-minute interval) and yet this intimidating stretch of time is not excessive in view of the complexity of Lawrence’s character and the differing points of view held both as to the man and the magnitude of his exploits.

An anthology of formidable names—as his brother showed—can be mustered in support of the claim that Lawrence was a great man in every sense of the word. Against this may be set the stark hostility of Richard Aldington’s book. The trouble with this extreme attack on what may be called the Lawrence legend is that it leaves in the air and unexplained the fact that Lawrence delighted and impressed such diverse men, to take a few at random, as Ronald Storrs, Allenby, Winston Churchill, and Bernard Shaw—none of them particularly easy to deceive.

With Major Lawrence, mercy is a passion. With me, it is merely good manners. You may judge which motive is the more reliable.

Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia film quote

However, in this particular context, the issue is less the truth about Lawrence, which, in any event, is something that may never be known, as the success of script and camera, director and actor, in giving a convincing account of what Lawrence did and, in doing so, in persuading the audience that the figure on the screen was capable of it.

In this respect, the film succeeds. It limits itself almost entirely to the desert, and, if its account of the fighting and of Lawrence’s part in it differs to some extent from the personal record set out in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, that unique work remains its inspiration.

There is a reference in the course of the action to Lawrence’s parentage; there is a short epilogue, something after the manner Shaw used in Saint Joan, which paradoxically comes at the beginning, and which sees various people after Lawrence’s funeral giving their differing opinions, but the spiritual, and the literal, home of Lawrence of Arabia is the desert.

The film, then, does not forget that Lawrence was an enigma, that there were contrasts and conflicts within him which baffled him as well as lesser people cut to a more consistent pattern. It does not, however, allow itself to be caught up in, and deflected by, them.

Mr. Lean is obviously determined to tell his adventure story (for that is, after all, what it is) in broad visual terms rather than the nagging verbal jargon of psychology; put Lawrence dressed in his Arab robes, on a camel with his band of fervid admirers round him and Turks to be attacked, and the camera will do the rest.

And superbly it does it. The film is shot in Super Panavision 70, and whatever that maybe it certainly produces spectacular effects. There is a sense of depth, of perspective, and when, for instance, a cloud of dust rises against a background of burning sand and burning sky it is possible to make a guess at the distance it is away. The big screen has frequently proved to be only too big; here it hardly seems big enough, and the implied compliment to Mr. Lean and his camera crew is considerable.

All this means that Mr. Peter O’Toole is obliged to make Lawrence a man of endurance and of action, a born and natural leader of men—and of Arabs in their own country and with their own savage and exacting standards rather than of his own race. Mr. O’Toole, although his height is a trifle disconcerting, achieves this supremely difficult task, and at the same time, he manages to mingle an arrogant awareness of Lawrence’s own contradictory qualities with humanity, and even humility.

Among those qualities, as the film has it, is blood-lust; the script, however, shies away from any deep exploration of the factors involved in his capture and flogging. At any rate, this Lawrence has the gift, as David Garnett stated the real Lawrence had, of giving to the most commonplace of remarks and sentences the incisive edge of personal style.

Sir Alex Guinness plays Prince Feisal with an air of weary, sceptical, civilized irony, almost as though he were Max Beerbohm in disguise. Mr. Jack Hawkins makes Allenby a general of authority and intelligence, although it is odd of him to compare Lawrence with Nelson—Raleigh would have been closer to the mark. There are occasional references to the political background of the times—the Sykes-Picot agreement, for instance, is mentioned. In the last analysis, however, Lawrence of Arabia remains a film for the eye rather than the mind.

Lawrence of Arabia movie review

One of the main themes of Lawrence of Arabia is the question of identity and the role of the individual in the larger political and social context. Lawrence’s experiences in the Middle East led him to question his own identity and the motivations of the British government. He becomes progressively compassionate to the Arab people and their culture, and he begins to question the true nature of the war and the actions of the British government.

One of the key essentials of the film’s success is its epic scale and attention to detail. The film was shot on location in the Middle East, and the production team went to great lengths to ensure the authenticity of the film’s depiction of the Arab world. The film’s cinematography, by Freddie Young, is widely considered to be some of the best in the history of cinema.

In addition to its technical and visual achievements, Lawrence of Arabia also explores deeply into the psyche of its main character, T.E. Lawrence. The film explores Lawrence’s internal conflicts and moral dilemmas as he becomes increasingly embroiled in the Arab Revolt. Peter O’Toole’s portrayal of Lawrence is widely considered to be one of the greatest performances in the history of cinema.

Along with its majestic views of the desert, Lawrence of Arabia’s characters are powerful. One can never get bored of watching nearly four hours of film. Peter O’Toole’s performance as T. E. Lawrence was wonderful, while was Alec Guinness’s Prince Feisal and Anthony Quinn’s Auda Abu Tayi. Michael Shaloub or Omar Sherif’s role of Sherif Ali ibn el Kharish is even more riveting. Born in a Christian family, Michael converted to Islam to marry famous Egyptian actress, Fatima Hamama.

The cultural presentation of the cast is flawless except that of language. I felt like Arabic would have been even more fascinating, at least for the Arabs. However, Lawrence’s heroism began in Aqaba and taking Deraa when he wanted to resign, he said he wanted to resign because he enjoyed killing. To me, when someone says he enjoys something he can be unstoppable in this matter, what Lawrence became, an unstoppable warrior.

However, there are some great lines from Lawrence of Arabia that I would love to focus on. When Lawrence went back to rescue Gasim who fell behind and considered his death was written by all the rest of the men in the group during the journey towards Aqaba, Lawrence believed “nothing is written unless we write it”. He saved the man only to kill him so as to keep the tribes united for an Arab revolt against the Ottoman empire.

The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.

Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia film quote

Lawrence expressed his concern about tribal prejudices and hatred to Sherifl Ali in the desert while he killed his guide, Tafas, for drinking water from his well, “So long as the Arabs fight tribe against tribe, so long will they be a little people, a silly people – greedy, barbarous, and cruel, as you are. To Ali, a well is everything, a human being is nothing.

Lawrence was greatly disturbed and frustrated to learn about the Sykes-Picot agreement at the end of the film. Mr Dryden revealed to him that through the agreement France and Britain are planning to share the empire after WWI. Dismayed, he said, “There may be honour among thieves, but there’s none in politicians.” Then Mr Dryden attempted to save Lawrence by saying, “If we have told lies, you’ve told half-lies. A man who tells lies, like me, merely hides the truth. But a man who tells half-lies has forgotten where he put it.”

There may be honour among thieves, but there’s none in politicians.

Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia film quote

Prince Feisal makes the statement to Bentley when asked about Lawrence’s influence in the bloodshed, “With Major Lawrence, mercy is a passion. With me, it is merely good manners. You may judge which motive is the more reliable.” This line highlights the contrasting approaches to mercy and their underlying motives between Prince Feisal and Lawrence.

When Prince Feisal says, “With Major Lawrence, mercy is a passion,” he implies that Lawrence is deeply driven by his compassion and sense of justice. Lawrence’s actions are guided by a genuine concern for the happiness of others and a desire to alleviate suffering. Feisal acknowledges that Lawrence’s commitment to mercy goes beyond mere formalities.

On the other hand, Prince Feisal states, “With me, it is merely good manners.” Here, he suggests that he exercises mercy as a matter of social etiquette rather than a deeply ingrained personal value. Feisal’s use of mercy may be more strategic, guided by political considerations and the need to maintain alliances and appearances.

By comparing their approaches to mercy, Prince Feisal suggests that Lawrence’s motive is more reliable. Feisal implies that Lawrence’s passion for mercy makes him more trustworthy and consistent in his actions. Lawrence’s commitment to justice and compassion is seen as a driving force that can be relied upon, while Feisal’s mercy, being grounded in good manners, may be subject to change depending on circumstances.

At the end of the war, in Cairo, Prince Feisal came to hackle the power with the British. When Lawrence’s usefulness was over for both Allenby and Feisal the following was advised to Lawrence by Feisal: “There’s nothing further here for a warrior. We drive bargains. Old men’s work. Young men make wars and the virtues of war are the virtues of young men. Courage and hope for the future. Then old men make the peace. And vices of peace are the vices of the old men. Mistrust and caution.”

Young men make wars and the virtues of war are the virtues of young men. Courage and hope for the future. Then old men make the peace. And vices of peace are the vices of the old men.

Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia film quote

In Lawrence of Arabia, the beauty of the desert is depicted with breathtaking visuals and poetic descriptions. The cinematography captures the vastness and allure of the Arabian landscape, immersing viewers in its awe-inspiring magnificence. Through stunning visuals and haunting storytelling, the film transports viewers to the heart of the desert similar to what we see in The English Patient. Lawrence of Arabia’s portrayal of the desert’s beauty is a tribute to the majesty and cruelty of nature simultaneously.

Daud’s falling into the quicksand was a heart-breaking thing to see, for me. It reminds it how important the water is. The hostility and violence against the Ottoman empire seem minimal when we consider the ruthless violence between the tribes like Harith, Howeitat, Ageyil and Ruala beni shakr for whom water is more important than human life.

Conclusion

I conclude by saying that Lawrence of Arabia is an immense achievement in the history of cinema. It is a film that is both epic in scale and intimate in its portrayal of its main character. The film’s technical and visual achievements, as well as its performances, are widely considered to be among the greatest in the history of cinema which delves deeply into the socio-political context of its setting to provide a complex depiction of the Middle East during World War I. It is a film that continues to be relevant and influential to this day.

Lawrence of Arabia 1962

10